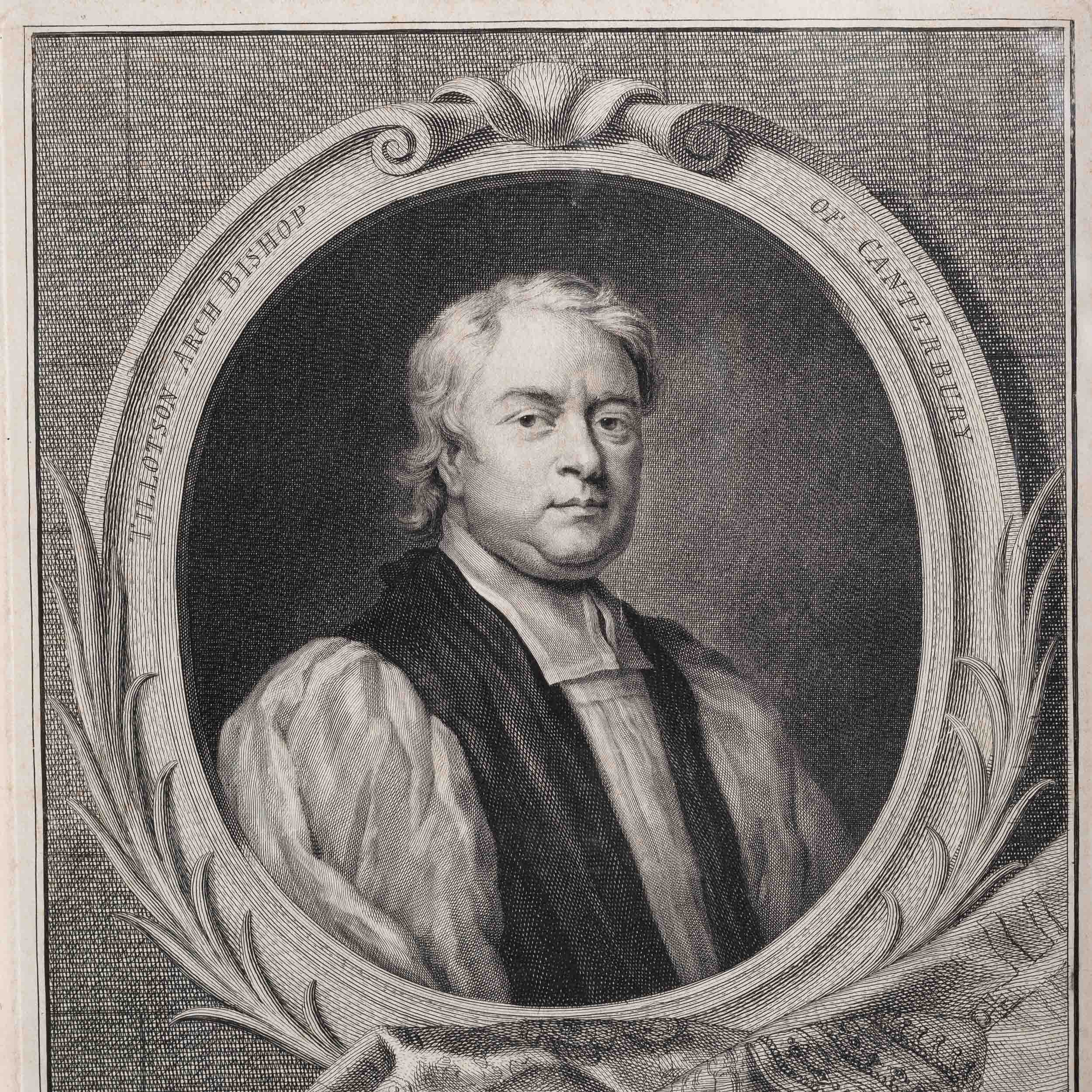

Archbishop Tillotson

A framed copper plate engraving of John Tillotson, Archbishop of Canterbury, by the Dutch engraver Jacobus Houbrackenn, struck in 1740.

£120

In stock

“TILLOTSON, JOHN (1630–1694), archbishop of Canterbury, was born at Old Haugh End, a substantial hillside house (still standing) in the chapelry of Sowerby, parish of Halifax, and baptised at the parish church of St. John the Baptist, Halifax. He was the second of four sons of Robert Tillotson (bur. 22 Feb. 1682–3, aged 91), a descendant of the family of Tilston of Tilston, Cheshire, and a prosperous clothworker at Sowerby, who became a member of the congregational church gathered at Sowerby in 1645 by Henry Root (d. 20 Oct. 1669, aged 80), but ceased his membership before Root’s death. His mother was Mary (bur. 31 Aug. 1667), daughter of Thomas Dobson, gentleman, of Sowerby; she was mentally afflicted for many years before her death.

According to tradition, Tillotson in his tenth year was placed at the grammar school of Colne, Lancashire; he was probably afterwards at Heath grammar school, Halifax, to the funds of which his father had made a small contribution. On 23 April 1647 he was admitted pensioner at Clare Hall, Cambridge, and matriculated on 1 July. His tutor was David Clarkson , who had succeeded the ejected Peter Gunning His ‘chamber-fellow and bed-fellow’ was Francis Holcroft; another chamber-fellow was John Denton. The master of Clare was Ralph Cudworth, who does not seem to have been popular in his college. Tillotson was not attracted by him, or by the school of ‘Cambridge platonists.’ In a letter to Root (dated Clare Hall, 6 Dec. 1649) he writes: ‘We have lesse hopes of procuring Mr. Tho. Goodwin for our master;’ the enforcement of the ‘engagement’ of allegiance to the then government ‘without a king or a house of lords’ was expected, and Tillotson, though he did not ‘at all scruple the taking of it,’ asked Root for his advice. He was a regular hearer of Thomas Hill (d. 1653) [q. v.], and a reader of William Twisse [q. v.]; the intellectual keenness of the Calvinistic theologians impressed him, but ‘he seemed to be an eclectic man, and not to bind himself to opinions’ (Beardmore). He was never a hard student, and kept no commonplace books. He studied Cicero and was familiar with the Greek Testament. At midsummer 1650 he commenced B.A. Not long after, ‘in his fourth year,’ he had a dangerous illness, followed by ‘intermittent delirium;’ a sojourn in the bracing air of Sowerby re-established his health.

He acted as probationer fellow from 7 April 1651 (having been nominated by mandamus from the government). Two vacancies occurring, he and another were elected fellows about 27 Nov. 1651. It was afterwards ruled that he had succeeded Clarkson in Gunning’s fellowship; Tillotson ‘was sure’ he had been admitted, not to Gunning’s fellowship, but to one legally void by cession (Beardmore). His first pupil was John Beardmore, his biographer; another was Clarkson’s nephew, Thomas Sharpe (d. 27 Aug. 1693, aged 60), founder of the presbyterian congregation at Leeds. Except on Sunday evenings he used no English with his pupils; ‘he spoke Latin exceedingly well.’ He had ‘a very great faculty’ in extemporary prayer, and a strong appetite for sermons, of which he usually heard four every Sunday and one each Wednesday. He proceeded M.A. in 1654, and kept the philosophy act with distinction in 1655.

At the end of 1656 or beginning of 1657 he went to London as tutor to the only son of Sir Edmond Prideaux [q. v.], to whom he acted as chaplain. Through Prideaux, then attorney-general, he obtained an exchequer grant of 1,000l. in compensation for building materials, meant for Clare Hall, but seized for the fortification of Cambridge. At his suggestion Joseph Diggons, formerly a fellow-commoner at Clare Hall, left the society an estate of 300l. a year. Tillotson was in London at the time of Cromwell’s death (3 Sept. 1658). His unpublished letter (8 Sept.) to Theophilus Dillingham, D.D. [q. v.], gives particulars of the proclamation of Richard Cromwell. He was present on the fast day at Whitehall, in the following week, when Thomas Goodwin, D.D. [q. v.], and Peter Sterry [q. v.] used in prayer the fanatical expressions which he afterwards reported to Burnet.

His change of feeling with regard to Goodwin is the first decisive indication that he had outgrown the prepossessions of his early training. He had been deeply influenced at Cambridge by Chillingworth’s ‘Religion of Protestants’ (1637); in London he had heard Ralph Brownrig [q. v.], become acquainted with John Hacket [q. v.], and formed a lasting friendship with William Bates, D.D. But to none of his contemporaries did he owe so much as to John Wilkins [q. v.] Towards the close of 1659 Wilkins had migrated from Oxford to fill the mastership of Trinity College, Cambridge, where, as Burnet says, ‘he joined himself … with those who studied to … take men off … from superstitions, conceits, and fierceness about opinions.’ Tillotson does not seem to have been then in residence; he met Wilkins for the first time in London shortly after the Restoration. The two men became very closely connected. Wilkins’s bent for physical research was not shared by Tillotson, though he was admitted a member of the Royal Society in 1672; meantime he was finding his way, under Chillingworth’s guidance, out of the Calvinism which Wilkins retained.

The order for restoring Gunning to his fellowship was dated 20 June 1660. Apparently he did not at once claim it, for Tillotson remained in possession till February 1661, when Gunning insisted on his removal; this was effected the very day before Gunning’s election as master of Corpus Christi College. Tillotson thought Gunning was moved by ‘some personal pique,’ and that an injustice was done him. He had not yet conformed, and was probably not in Anglican orders. The date of his ordination, without subscription, by Thomas Sydserf [q. v.] is conjectured by Birch to have been ‘probably in the latter end of 1660 or beginning of 1661.’ He was one of the nonconforming party to whom it was intended to offer preferment in the church. Had Edmund Calamy the elder [q. v.] accepted the bishopric of Coventry and Lichfield (kept open for him till December 1661), Tillotson was designed for a canonry at Lichfield. He was not in the commission for the Savoy conference, but in July 1661 he is specified by Baxter among ‘two or three scholars and laymen’ who attended as auditors on the nonconforming side. His first sermon was preached for his friend Denton at Oswaldkirk, North Riding of Yorkshire, but the date is not given. In September 1661 he took ‘upon but short warning’ Bates’s place in the morning exercise at Cripplegate; the sermon was published (at first anonymously) and contains a characteristic quotation from John Hales of Eton. Some time in 1661 he became curate to Thomas Hacket, vicar of Cheshunt, Hertfordshire (afterwards bishop of Down and Connor), and deprived (1694), on Tillotson’s advice (1691), for ‘scandalous neglect of his charge.’ At Cheshunt he lived with Sir Thomas Dacres ‘at the great house near the church,’ a house which he afterwards rented as a summer resort in conjunction with Stillingfleet. It seems probable that his was the signature, which appears as ‘John Tillots,’ to the petition presented on 27 Aug. 1662 (three days after the taking effect of the uniformity act) asking the king to ‘take some effectual course whereby we may be continued in the exercise of our ministry’ (Halley, Lancashire, 1869, ii. 213). He won upon an anabaptist at Cheshunt, who preached ‘in a red coat,’ persuading him to give up his irregular ministry. Frequently he preached in London, especially for Wilkins at St. Lawrence Jewry. On 16 Dec. 1662 he was elected by the parishioners, patrons of St. Mary Aldermanbury, to succeed Calamy, the ejected perpetual curate. He declined; but in 1663 (mandate for induction, 18 June) he succeeded Samuel Fairclough [q. v.], the ejected rector of Kedington, Suffolk, being presented by Sir Thomas Barnardiston [q. v.] Happening to supply the place of the Tuesday lecturer at St. Lawrence Jewry, he was heard by Sir Edward Atkyns (1630–1698) [q. v.], then a bencher of Lincoln’s Inn, by whose interest he was elected (26 Nov. 1663) preacher at Lincoln’s Inn. Before June 1664 he resigned Kedington in favour of his curate; his own preaching had been distasteful to his puritan parishioners. Soon afterwards he was appointed Tuesday lecturer at St. Lawrence Jewry, of which church Wilkins was rector. This appointment, and the preachership at Lincoln’s Inn, he retained until he became archbishop. Hickes affirms, and Burnet does not deny, that Tillotson gave the communion in Lincoln’s Inn Chapel to some persons sitting; this practice he had certainly abandoned before 17 Feb. 1681–2, the date of his letter on the subject. Hickes further says that to avoid bowing at the name of Jesus ‘he used to step and bend backwards, casting up his eyes to heaven,’ whence Charles II said of him that ‘he bowed the wrong way, as the quakers do when they salute their friends.’

Tillotson cultivated his talent as a preacher with great care. He studied, besides biblical matter, the ethical writers of antiquity, and among the fathers, Basil and Chrysostom. The ease of his delivery made hearers suppose that he only used short notes, but he told Edward Maynard [q. v.], his successor at Lincoln’s Inn, ‘that he had always written every word,’ and ‘us’d to get it by heart,’ but gave this up because ‘it heated his head so much a day or two before and after he preach’d.’ His example led William Wake [q. v.] ‘to preach no longer without book, since everybody, even Dr. Tillotson, had left it off.’ His gifts had not availed him with a country parish, but in London he got the ear, not only of a learned profession, but of the middle class. People who had heard him on Sunday went on Tuesday in hope of listening again to the same discourse. Baxter, who had ‘no great acquaintance’ with him, listened to his preaching with admiration of its spirit. Hitherto the pulpit had been the great stronghold of puritanism, under Tillotson it became a powerful agency for weaning men from puritan ideas. The consequent change of style was welcomed by Charles II, who, says Burnet, ‘had little or no literature, but true and sound sense, and a right notion of style;’ under royal favour, cumbrous construction and inordinate length were replaced by clearness and what passed in that age for brevity; the mincing of texts and doctrines was superseded by addresses to reason and feeling, in a strain which, never impassioned, was always suasive.

When Tillotson made suit during 1663 for the hand of Oliver Cromwell’s niece, Elizabeth French, her stepfather, John Wilkins, ‘upon her desiring to be excused,’ said: ‘Betty, you shall have him; for he is the best polemical divine this day in England.’ He had published nothing as yet of a polemical kind (Birch), but Wilkins rightly judged the effect of his pulpit work, as a practical antidote to the danger of popery, supervening upon the prevalent irreligion. Such was the tenor of his first famous sermon, ‘The Wisdom of being Religious’ (1664); the dedication to the lord mayor curiously anticipates the tone of Butler’s ‘advertisement’ to the ‘Analogy’ (1736), with this difference, that by Butler’s time the atheism of the age had (largely owing to the labours of Tillotson’s school) been reduced to deism. His expressly polemic writing against Roman catholicism began with his ‘Rule of Faith’ (1666) in answer to John Sergeant [q. v.] Hickes thought he owed much to the suggestions of Zachary Cradock [q. v.], which Burnet denies. The work is addressed to Stillingfleet, and has an appendix by him. John Austin (1613–1669) [q. v.] took part in the discussion, which really turned on the authority of reason in religious controversy. An argument against transubstantiation, introduced by Tillotson in his ‘Rule of Faith’ and developed in his later polemical writings, led Hume to balance experience against testimony in his ‘Essay on Miracles’ (1748).

In 1666 Tillotson took the degree of D.D. His preferment was not long delayed. He became chaplain to Charles II, who gave him, in succession to Gunning, the second prebend at Canterbury (14 March 1670), and promoted him to the deanery (4 Nov. 1672) in succession to Thomas Turner (1591–1672) [q. v.], though Charles disliked his preaching against popery, and his sermon at Whitehall (early in 1672) on ‘the hazard of being saved in the Church of Rome’ had caused the Duke of York to cease attending the chapel royal. With the deanery of Canterbury he held a prebend (Ealdland) at St. Paul’s (18 Dec. 1675), exchanging it (14 Feb. 1676–7) for a better (Oxgate). This last preferment was given him by Heneage Finch, first earl of Nottingham [q. v.], at the suggestion of his chaplain, John Sharp (1645–1714) [q. v.], whose father had business connections with Tillotson’s brother Joshua (a London oilman, whose name appears as ‘Tillingson’ in the directory of 1677; he died on 16 Sept. 1678).

It is clear from Baxter’s account that Birch is wrong in connecting Tillotson (and Stillingfleet) with the proposals for comprehension of nonconformists prepared by Wilkins and Hezekiah Burton [q. v.] in January 1668. It was in October or November 1674 that Tillotson and Stillingfleet first approached the leading nonconformists, through Bates. Tillotson and Baxter jointly drafted a bill for comprehension, which Baxter prints; those formerly ordained ‘by parochial pastors only’ were now to be authorised by ‘a written instrument,’ purposely ambiguous. The negotiation was ended by a letter (11 April 1675) from Tillotson to Baxter, announcing the hopelessness of obtaining the concurrence of the king or ‘a considerable part of the bishops,’ and withholding his name from publication. He preached, however, at the Yorkshire feast (3 Dec. 1678), in favour of concessions to nonconformist scruples. He took great interest in the efforts made by the nonconformist Thomas Gouge [q. v.] for education and evangelisation in Wales, acted as a trustee of Gouge’s fund, and preached his funeral sermon (1681) in a strain of fervid eulogy.

In May 1675 Tillotson visited his father, who had ‘traded all away,’ and to whose support he contributed 40l. a year. He preached at Sowerby on Whitsunday (23 May) and the following Sunday at Halifax. Oliver Heywood reports the puritan judgment on his sermons as plain and honest, ‘though some expressions were accounted dark and doubtful.’ Halifax tradition, as reported by Hunter, represents Robert Tillotson as saying ‘that his son had preached well, but he believed he had done more harm than good.’ His connection with William of Orange, according to a hearsay account preserved by Eachard, dates from November 1677, when William visited Canterbury after his marriage; the details, as Birch has shown, are not trustworthy.

Much stir was made by his sermon at Whitehall on 2 April 1680, in vindication of the protestant religion ‘from the charge of singularity and novelty.’ He had prepared his sermon with ‘little notice,’ having been called on owing to the illness of the appointed preacher. In an unguarded passage he maintained that private liberty of conscience did not extend to making proselytes from ‘the establish’d religion,’ in the absence of a miraculous warrant. According to Hickes, who is confirmed by Calamy, ‘a witty Lord’ signalised this as Hobbism, and procured the printing of the sermon by royal command. Gunning complained of it in the House of Lords as playing into the hands of Rome. John Howe [q. v.], in the same strain, drew up an expostulatory letter, and delivered it in person. At Tillotson’s suggestion they drove together to dine at Sutton Court with Lady Fauconberg (Cromwell’s daughter Mary), and discussed the letter on the way, when Tillotson ‘at length fell to weeping freely’ and owned his mistake. Yet the passage was never withdrawn, and is scarcely mended by a qualifying paragraph added in 1686. The nonconformists never treated Tillotson’s doctrine as levelled against themselves, knowing that by ‘the establish’d religion’ Tillotson meant protestantism. It is plain, however, that the principle of obedience to constituted authority, as providential, was accepted by him from the period of the engagement (1649) onwards. His famous letter (20 July 1683) to William Russell, lord Russell [q. v.], printed ‘much against his will,’ maintains the unlawfulness of resistance ‘if our religion and rights should be invaded;’ his subsequent exception of ‘the case of a total subversion of the constitution’ is rather lame in argument, though quite consistent with his real mind, protestantism being identified with the constitution. He is said to have drawn up the letter (24 Nov. 1688) addressed to James II by Prince George of Denmark [q. v.] on his defection from his father-in-law’s cause; that this letter identifies the Lutheran religion with that of the church of England is no disproof of the story.

He preached before William at St. James’s on 6 Jan. 1689; on 14 Jan. a small meeting was held at his house to consult about concessions to dissenters, with Sancroft’s approval. On 27 March he was made clerk of the closet to the king; in August the Canterbury chapter appointed him to exercise archiepiscopal jurisdiction, owing to the suspension of Sancroft; in September he was nominated to the deanery of St. Paul’s (elected 19 Nov., installed on 21 Nov.). Apparently he had declined a bishopric, but, on his kissing hands, William intimated that he was to succeed Sancroft. This was on Burnet’s advice, and was contrary to the inclination of Tillotson, who honestly thought he could do more good as he was, and have more influence, ‘for the people naturally love a man that will take great pains and little preferment.’ In a later paper (13 March 1692) he allows ‘that there may perhaps be as much ambition in declining greatness as in courting it.’

The Toleration Act was carried without difficulty (royal assent 24 May 1689); a bill for comprehension was passed by the lords with some amendments, but on reaching the commons it was held over for the judgment of convocation. Burnet felt that this would ruin the scheme. Tillotson’s strong common-sense was alive to the odium of a new parliamentary reformation, and urged William to summon convocation and appoint a smaller body to frame proposals for its consideration. A commission was issued to thirty divines (including ten bishops) on 13 Sept. 1689. On the same day Tillotson formulated seven concessions which would ‘probably be made’ to nonconformists. The commission met on 3 Oct., and held sittings till 18 Nov. Very extensive alterations in the prayer-book found favour with a majority, the chief revisers being Burnet, Stillingfleet, Simon Patrick [q. v.], Richard Kidder [q. v.], Thomas Tenison [q. v.], and Tillotson (full details were first given in ‘Alterations in the Book of Common Prayer,’ &c., printed by order of the House of Commons, 2 June 1854). Tillotson also had a scheme for a new book of homilies.

Convocation met on 21 Nov. Much canvassing had taken place for the elected members of the lower house, who were predominantly high churchmen, the man of most note being John Mill [q. v.] Tillotson was proposed as prolocutor by John Sharp (1645–1714) [q. v.], his successor in the deanery of Canterbury. William Jane [q. v.] was elected by 55 votes to 28; his Latin speech, on being presented to the upper house, was against amendment, and closed with the words ‘Nolumus leges Angliæ mutari.’ The leaders of the lower house ignored the commission, declining to give nonjurors occasion to say they were for the old church as well as for the old king. Ineffectual attempts were made to win them over. On 24 Jan. 1690 convocation was adjourned, and dissolved on 6 Feb.

The state of contemporary feeling is well illustrated by the outcry against Tillotson’s sermon on ‘the eternity of hell torments,’ preached before the queen on 7 March 1690. He sought to give reality to the doctrine, presenting it as a moral deterrent, but was accused of undermining it to allay Mary’s dread of the consequences of her action as a daughter. Hickes makes the groundless suggestion that he borrowed his argument from ‘an old sceptick of Norwich,’ meaning John Whitefoot (1601–1699), author of the funeral sermon for Joseph Hall [q. v.] Whitefoot’s ‘Dissertation,’ which maintains the destruction of the wicked, is printed in Lee’s ‘Sermons and Fragments attributed to Isaac Barrow,’ 1834, pp. 202 sq. (cf. Barrow, Works, ed. Napier, 1859, i. p. xxix). Tillotson’s reluctance to accept the see of Canterbury was overcome on 18 Oct. 1690, but he stipulated for delay, and that he should not be made ‘a wedge to drive out’ Sancroft. He was not nominated till 22 April 1691, elected 16 May, and consecrated 31 May (Whitsunday) in Bow church by Peter Mews [q. v.], bishop of Winchester, and five other bishops. Sancroft, who was still at Lambeth, refused to leave till the issue of a writ of ejectment on 23 June. Tillotson received the temporalities on 6 July, and removed to Lambeth on 26 Nov., after improvements, including ‘a large apartment’ for his wife. No wife of an archbishop had been seen at Lambeth since 1570.

His primacy was brief and not eventful. He exercised a liberal hospitality, and showed much moderation both to nonjurors and to nonconformists. He took no part in political affairs. No business was entrusted to convocation during his primacy. He seems to have initiated the policy of governing the church by royal injunctions addressed to the bishops; those of 13 Feb. 1689 were probably, those of 15 Feb. 1695 certainly, drawn up on his advice. Sharp consulted him about the case of Richard Frankland [q. v.], who had set up a nonconformist academy for ‘university learning.’ Tillotson replied (14 June 1692) that he ‘would never do anything to infringe the act of toleration,’ and then suggested, as ‘the fairest and softest way of ridding your hands of this business,’ that Sharp should explain to Frankland that the grounds for withdrawing a license were applicable also to conformists.

In 1693 appeared his four lectures on the Socinian controversy. He had delivered them at St. Lawrence Jewry in 1679–80, and now published them as an answer to doubts of his orthodoxy, based upon his intimacy with Thomas Firmin [q. v.], whose philanthropic schemes he had encouraged. His connection with Firmin had indeed been singularly close. He had acted as godfather to his eldest son (1665); as dean of Canterbury (1672) he had trusted him to find supplies for the lectureship at St. Lawrence Jewry; he now welcomed him to his table at Lambeth. The four lectures prove conclusively that Tillotson had no Socinian leaning; but their courteous tone and their recognition of the good temper of Socinian controversialists, ‘who want nothing but a good cause,’ gave offence. An incautious expression in a supplementary sermon on the Trinity (1693), missed by Leslie (Charge of Socinianism, 1695) but noted by George Smith (1693–1756) [q. v.], opened the way to the position afterwards taken by Samuel Clarke (1675–1729) [q. v.], assigning to our Lord every divine perfection, save only self-existence. Thus Tillotson unwittingly dropped the first hint of the Arian controversy, which arose on the exhaustion of the Socinian argument. Firmin employed Stephen Nye [q. v.] on a critique of Tillotson’s lectures. Shortly before his death Tillotson read these ‘Considerations’ (1694), and remarked to Firmin, ‘My lord of Sarum shall humble your writers.’ Burnet’s ‘Exposition’ was not published till 1699, but Tillotson had already revised the work in manuscript, and in one of the last letters he wrote (23 Oct. 1694) expresses his satisfaction, except on one point, the treatment of the Athanasian creed, adding, ‘I wish we were well rid of it.’ He revised also a portion of the ‘Vindication’ (1695) of his four sermons by John Williams (1634–1709) [q. v.]

At the end of 1687 Tillotson had received the warning of an apoplectic stroke. He was seized with paralysis in Whitehall chapel on Sunday, 18 Nov. 1694, but remained throughout the service. His speech was affected, but his mind clear. He is said to have recommended Tenison as his successor. During the last two nights of his life he was attended by Robert Nelson [q. v.], his correspondent from 1680 and his attached friend, though a nonjuror. He died in Nelson’s arms on 22 Nov. 1694, and was buried on 30 Nov. in the chancel of St. Lawrence Jewry, where is a monument (erected by his widow) with medallion bust (engraved in Hutchinson’s ‘Life’). Burnet preached a funeral sermon. He died penniless; ‘if his first-fruits had not been forgiven him by the king, his debts could not have been paid.’ His posthumous sermons afterwards sold for two thousand five hundred guineas. His library was put on sale, 9 April 1695, at fixed prices (see Bibliotheca Tillotsoniana, 1695).

He married (23 Feb. 1664) Elizabeth (d. 20 Jan. 1702), only child of Peter French, D.D. (d. 17 June 1655), by the Protector’s sister Robina, who, after a year of widowhood, married, as her second husband, John Wilkins. Neither of his children survived him; his elder daughter, Mary (d. November 1687), married James Chadwick (d. 1697), and left two sons and a daughter (who married a son of Edward Fowler, D.D. [q. v.]); his younger daughter, Elizabeth, died in 1681. To Mrs. Tillotson, in accordance with a promise of William III, tardily fulfilled, was granted (2 May 1695) an annuity of 400l.; by the efforts of Dean William Sherlock [q. v.] and Robert Nelson this was increased (18 Aug. 1698) to 600l., enabling her to provide for the education of her nephew, Robert Tillotson, as well as to maintain two of her grandchildren.

Testimony is unanimous as to Tillotson’s sweetness of disposition, good humour, absolute frankness, tender-heartedness, and generosity. A sensitive man, he bore with an unruffled spirit the calumnious insults heaped upon him by opponents. He spent a fifth of his income in charity. His interest in learning is shown by his encouragement of Matthew Poole [q. v.], and by his obtaining preferment for George Bull [q. v.] and Thomas Comber, D.D. (1645–1699) [q. v.]; his appreciation of intellectual power by his editorial work in connection with the manuscripts of Wilkins and Isaac Barrow (1630–1677) [q. v.], though it is true that his modernising of Barrow’s style proves the wisdom of not permitting him to mend the English of the collects. He was perhaps the only primate who took first rank in his day as a preacher, and he thoroughly believed in the religious efficacy of the pulpit; ‘good preaching and good living,’ he told Beardmore in 1661, ‘will gain upon people.’

The first collected edition of Tillotson’s works contains fifty-four sermons and the ‘Rule of Faith;’ two hundred were added in succeeding editions, edited by Ralph Barker, 1695–1704, 8vo, 14 vols., and reprinted 1728, fol., 3 vols. The best edition is edited, with ‘life,’ by Birch, 1752, fol., 3 vols. (contains 255 sermons, and is otherwise complete). Editions of single sermons and of the works, and selections from them, are very numerous; the latest is a selection annotated by G. W. Weldon, 1886, 8vo. The transubstantiation discourse was translated into French, 1685, 12mo; a selection of the sermons in French appeared at Amsterdam, 1713–18, 2 vols. 8vo; in German at Dresden, 1728, 8vo; and Helmstadt, 1738–9, 8 vols. 8vo (with life, revised by Mosheim). Transcripts in French of some of his sermons, dated 1679–80, are in Addit. MS. 27874. Some letters to Sir R. Atkins of 1686–9 are in Addit. MS. 9828.

Besides the monument in St. Lawrence Jewry, there is a mural memorial in the parish church at Halifax. In Sowerby church is a full-length statue by Joseph Wilton, R.A. (1722–1803), erected at the cost of George Stansfeld (1725–1805) of Field House. Tillotson’s portrait was painted by Lely during his tenure of the deanery, and in 1694 by Kneller. The Lely portrait was engraved by A. Blooteling and the Kneller by Houbraken, R. White, J. Simon Faber, Vertue, and many others. In a third portrait by Mary Beale, now at Lambeth (engraved by White and Vanderbank), he wears a wig, and is the first archbishop of Canterbury so depicted. A fourth portrait (also by Mary Beale) was bought for the National Portrait Gallery in 1860. In person he was of middle height, with fresh complexion, brown hair, and large speaking eyes; when young very thin, but corpulent as he advanced in years.”

– Dictionary of National Biography

Recently Viewed Items

-

A small cast plaster flowerhead roundel,

£40 -

A quantity of 18″ black marble tiles

£20 each incl. VAT (approx £100 per sq m incl. VAT)A quantity of 18″ black marble tiles

each with gold veining and quartz inclusions, evenly distributed across a dark base,£20 each incl. VAT (approx £100 per sq m incl. VAT)