An historically important, richly ornamented, Carolean plaster ceiling,

the central oval with a border of wrythen fruiting acanthine scrolls and spirally moulded ribbons within a square field, compartmentalised into spandrels with stiff-leaf moulded ribs, each quarter centred either by an armorial cartouche or a stop-fluted vase issuing vines and roses; four short and two long rectangular panels line two opposing sides of the square - each cast in deep relief with fruiting boughs - and the rectangular whole is bordered by a lavish cornice, each length cast with floral and fruiting scrolls and centred with an armorino,

POA

In stock

Photo Credit: Photo 1&6 – copyright: Bob Smith 2004 for World of Interiors. Reproduced with kind permission from Conde Nast.

The Salvage of the Wheelergate Ceiling

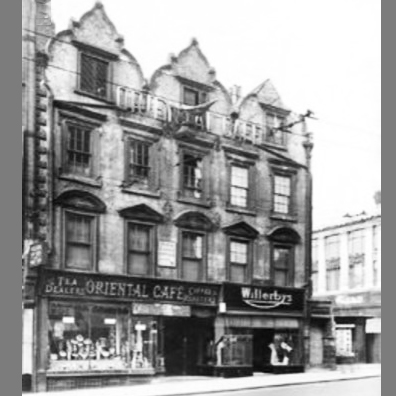

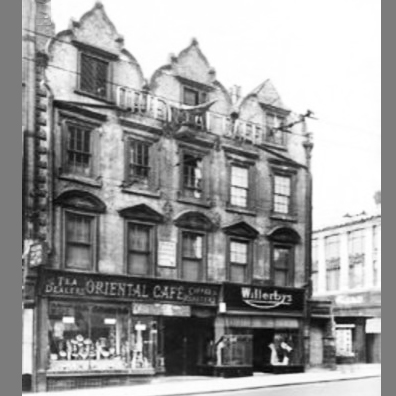

This historic and spectacular ceiling was saved by the Nottingham Corporation Highways Department when, in 1961, a Merchant’s House at 4-6 Wheeler Gate in central Nottingham – the building it adorned – was demolished. It had stood there for 280 years and there was an outcry. It couldn’t be saved. The building had been occupied by “The Oriental Café” for the latter 60years (in its Edwardian heyday a rather grand venue); originally built as a grand town house for a Merchant, it is thought was the city residence of the Earl of Mansfield in the 18th Century.

Having survived the demolition, albeit sawn into sections, the ceiling languished in a highways depot for 20years. But a home for it was ultimately found and it was installed at Holmpierepoint Hall, a Tudor mansion on the River Trent. It lasted there until 1998 when restorations to the Hall determined that it had to be disassembled again. It was put down in the stables.

In stepped Peter Hone, (these days LASSCO’s consultant Plaster Caster), who had heard of the plight of the historic plasterwork via Salvo news – the Architectural Salvage trade newspaper. A race up the motorway in a clapped-out old van and a somewhat over-loaded crawl back down the M1 ensued.

The ceiling has, once again, remained in storage for a couple of decades, but during that time some painstaking restoration work has been undertaken. Countless layers of paint have been removed to reveal virtuoso plasterwork in wonderful detail.

Rupert Van der Werff, formerly of Sotheby’s, is quoted in World of Interiors, in May 2004:

“To find a ceiling of this quality is rare. For it not to be in situ is very, very rare.”

We suspect it may, in fact, be unique.

***

The History of Wheelergate

There are some accounts of the ceiling in situ at 4-6 Wheelergate in Edwardian times– recorded by Harry Gill, writing for the Thoroton Society in 1912*:

“The house …near the top of Wheelergate is now given up entirely to business pursuits; and while this has taken away some of its interest, it has not robbed it of all its old-time dignity and importance. Judging by the style of architecture, the shaped and moulded gables, the heavy stone architraves and pediments to the windows, the stone quoins at the angles, and the elaborate plaster enrichment to the ceiling of the principal room, I am of opinion that this building was erected during the reign of Charles II, to serve as the town-house of a gentleman. I can well remember the demolition of the old Water Offices—the adjoining building on the south—when sufficient evidence was disclosed, to shew that this house was built in between older premises. It is doubtless one of the first of the mansions that were “built soon after the Restoration,” and tradition may be right in ascribing it to Lord Mansfield.”

J. Holland Walker, also writing for the Thoroton Society but 20years later (and three decades before the Wheeler Gate demolition), in “Itinerary of Nottingham, Transactions of the Thoroton Society, 1925-35” also describes the building, but gives it a slightly earlier date:

“The house, which is now divided into tenements, the lower of which is occupied by Messrs. Armitage as “The Oriental Café”, is of extreme interest to the architectural student for it forms a link which connects the old Gothic traditions of building with the Renaissance type of house. Its upper stories were illuminated by what are perhaps the earliest sash windows in Nottingham and it has very many other features which are of interest to the antiquary. The wonderful ceiling in the shop is an excellent version of the plaster work of the 17th Century and it is more or less contemporary with the publication of Milton’s Paradise Lost” … [1667]. “As far as I know there is no documentary evidence of the date when this house was built, but I think it is probable that it was erected in the closing years of Charles I reign, and it is believed….” [in the 18th Century] “… to have been the town house of the Earl of Mansfield. There seems no proof of this fact, but at any rate, I was firmly held by the late Mr Harry Gill who knew more about these matters than most people.”

Holland Walker, writing yet later, in 1931, records that it was under the, then new, ceiling that an historic meeting took place –

“In 1688 an event of the greatest importance occurred at the Malt Cross. Public feeling had been settling against James II and his policy and at last it had come to a head. The Duke of Devonshire was the great leader in this neighbourhood and after a conference with the leading gentry of the Midlands, which had taken place probably in what is now the Oriental Cafe in Wheeler Gate, the Duke, accompanied by Lord Delamere, Sir Scroop Howe, Mr. Hutchinson and others, proceeded to the Malt Cross where they read a declaration that they had decided to throw in their lot with William, Prince of Orange. The market folk gladly followed their lead and as far as the Midlands were concerned James’s cause was lost.”

If Holland Walker is correct, this ceiling, then newly made, bore witness to a momentous historical event – a turning point in the Glorious Revolution of 1688. William Cavandish, 3rd Earl of Devonshire 1640 -1707 was part of the “Immortal Seven” group that invited William III, Prince of Orange to depose James II of England during the Glorious Revolution (he was rewarded with the elevation to Duke of Devonshire in 1694). The Earl certainly did make Nottingham the Northern headquarters for the rebellion and, with its spectacular new ceiling, the Wheelergate house – centrally located – it would have been a splendid room to have held court and garner support for his Protestant cause; research continues to see if 4-6 Wheelergate can be verified as the location of this meeting.

(Elsewhere Walker Holland makes mention of another later resident at the house – of a later era: “… the great Sir Charles Napier, the conqueror of Sind … [dating to when] he occupied the … post of Commander of the troops brought into Nottingham … to deal with … the Chartist riots”.… in 1810.)

***

Whether the building dates to before the Commonwealth, or after, the spectacular ceiling within can only be a very early example of its type. The plaster ceilings of Inigo Jones’ ground-breaking Queen’s House at Greenwich were still radical and new when this design, clearly to the Inigo Jones format, was modelled in situ in Nottingham; it would have been the talk of the town – the like of which they’d never have seen before. Jones’ innovative designs – a revolutionary new approach – was also evident in his plaster ceiling in the Banqueting Hall, Whitehall c.1622. In “Decoration in England 1640-1760” – Francis Lenygon explains:

“With Inigo Jones, the modelled plaster underwent a change. Instead of a surface filled with intricate and all-over designs, or ornament contained within small panels, the setting out became the leading feature, and this setting out has a definite and emphasised centre.”

Lenygon continues:

“The main lines were greatly simplified; the ceiling was divided by heavy moulded ribs into a few compartments, generally a large central oval, circle or rectangular panel which is surrounded by smaller subsidiary panels. The wide soffits of these ribs are enriched with classic detail, such as guilloche or by scrolling acanthus, or wreaths of husks, leaves or closely packed fruits, while the sides are moulded and sometimes also modillioned. The centre is left blank, as in the ceiling of the saloon and hall at Coleshill [c.1662], and the porch to the Great Hall at Kirby. It is possible that the central panel was destined for a decorative painting.”

This is an accurate description of all the features we find in the Wheelergate ceiling.

The Ceiling For Sale

We’ve now managed to re-hang the central oval at LASSCO Three Pigeons – half a ton of plaster. And, correctly orientated once again – a Glorious Revolution – it looks truly spectacular. We will be able to advise on the logistics of the potential re-instatement of the whole ceiling to any buyer – no small undertaking – please enquire.

***

Sources:

“The Plaster Puzzle” Matt Gibberd, World of Interiors May 2004 pp180-83

* In “Nottingham in the 18th century, Transactions of the Thoroton Society, 16” )

http://www.nottshistory.org.uk/articles/tts/tts1912/gill1912p2.htm

&

http://www.nottshistory.org.uk/whatnall1928/oriental_cafe.htm

Francis Lenygon “Decoration in England 1640 to 1760” B.T Batsford ltd , London, 1914