Click and Collect – Please contact us to arrange collection or delivery of this item

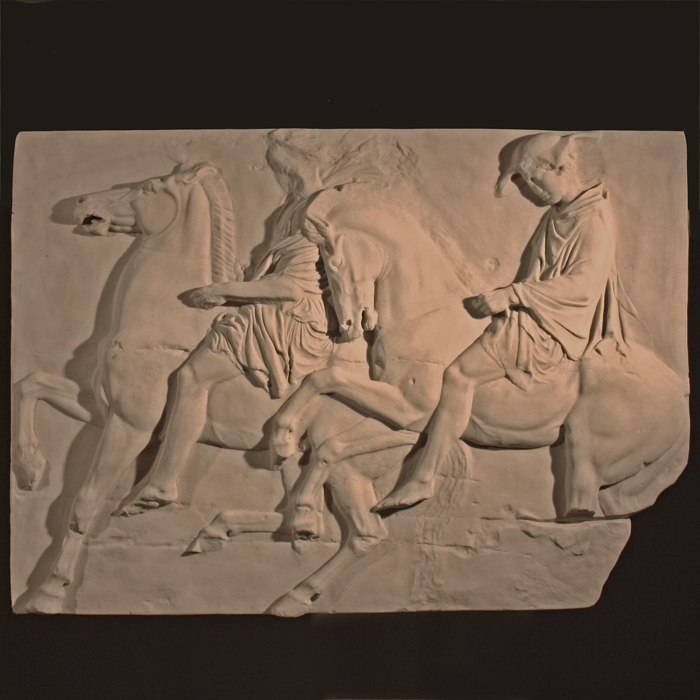

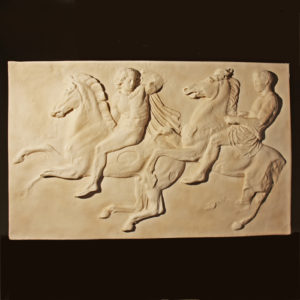

The Parthenon Marbles: A sculptural relief from the West façade of the Doric Frieze

cast in patinated resin after Panel IX, one of the 5th Century BC Pentelic marble originals held in the Acrolpolis Museum, Athens,

the rectangular panel cast in low-relief with two horsemen, wearing tunics, reining in their mounts, the second wearing a wide-brimmed hat,

£995

In stock

A summary of the original context and history of the Parthenon Marbles:

The astonishing Parthenon temple was built on the Acropolis in Athens between 447 and 432 BC. Its construction was part of a series of major works undertaken in the aftermath of the Persian Wars (490-480 BC) and the destruction wrought by the Persians. Pericles, who dominated Athenian political life from 464 to 429 BC, entrusted the overseeing of the Parthenon’s construction to the sculptor Phidias, who worked with the architects Iktinos and Kallikrates.

The large low relief sculpture reproduced here, one of three, is from the Doric Frieze of the Parthenon which comprises only one of the three main sculptural series on the temple exterior.

Most prominent of these three were the Pediment sculptures – almost entirely carved “in the round” and occupying the triangular pediments to each end of the temple. These pediment sculptures suffered most from the huge explosion in 1687 that saw the decimation of the Parthenon when the Venetians scored a direct artillery hit on the temple as they laid siege to the ruling Ottomans. The Ottoman army had been using it as a secure store, or magazine, for vast amounts of gunpowder. Tragically, such was the resulting explosion on that day, three hundred people lost their lives, the marble roof was blown off and large parts of the ancient sculptures were shattered; some were entirely lost, including the central sections of the pediment sculptures.

Secondly, an outer frieze – in the Ionic order – wrapped the exterior of the Parthenon temple, above the “peristyle” (the colonnade). This comprised large rectangular “metopes” – panels of figural sculpture in deep relief – each rectangle separated by a “triglyf” (a block with three vertical raised bands).

Thirdly, the Doric order frieze was an inner frieze, found high-up inside the peristyle, under cover and in the shade. It was of lower relief sculpture – a continuous band wrapping the monument. These wonderful sculptures of horses and Athenians, their narrative still not fully understood, now form a large part of the “Elgin Marbles” held in the Duveen Gallery at The British Museum in London. Surprisingly to the modern eye, these three sculptural schemes were brightly painted in a limited pallet and part gilded.

Whilst the pediment sculptures and Ionic outer frieze depicted the realm of the gods – the birth of Athena, or mythic stories including the conflicts that told the formation of Athens such as the Centauramachy and the Amazonamachy – the low-relief inner frieze, was more temporal in subject matter. Although still slightly cryptic, here we see a Panathanaic procession – real Athenians processing through their fabulous city on horse and by foot along the Panathanaic Way to pay homage to their goddess Athena. The eloquence of the sculptures is truly astonishing – the movement and drama in the successive ranks of horses breath-taking, as was the scale of this monument built by hand, high on the Acropolis, nearly 2500 years ago.

Nothing remains of the focus of the Temple: a 40’ statue of Athena – thought to have been made of olive wood, ivory and precious metals, that dominated the cavernous interior.

Just over 100years after the explosion, Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin, Britain’s ambassador to the Ottoman Empire set about the Acropolis ancient ruins and in a dubious act of “architectural salvage” that many (including many of his contemporaries) see as a barbarous act of vandalism and theft, extracted over half of the sculptures that remained – including sawing off some that were still in situ on the Parthenon. He shipped his acquisitions. They were later sold to The British Museum.

The state of Greece was born a few years after Elgin’s looting ended in 1812. Mourning the loss of the marbles from the de-nuded temple, Greece was soon petitioning for the return of the marbles. This continues today.

The history of casting copies of the sculptures:

The early years saw a concerted effort to protect what remained and discover how the fragments might be pieced back together. The various parts of the three sculptural schemes were, by then, scattered across different collections in Europe. The main body of “Elgin Marbles” were in London; Athens had retained a quantity despite Elgin – whether still embedded in the architrave of the temple or removed for safe-keeping. Paris had notable sculptures; over time yet more fragments were unearthed abroad in the verdant gardens of Grand Tourists who had helped themselves. And more fragments were being continually unearthed, throughout the 19th Century in digs and clearances on the Acropolis itself – these were carefully locked in catacombs underneath the Acropolis and were closely guarded.

The British Museum was however instrumental in commissioning casts of all and any panels or fragments, either held elsewhere or newly discovered, that would aid a complete piecing together of the friezes – a process that continued for decades. They adhered the plaster “joins” to the marble originals and re-jigged the order of the panels accordingly.

Different attempts to cast the sculptures held in London – no small undertaking – ultimately lead to different editions being distributed around the world. There are a few extant full-size sets of the Doric frieze to be found in Europe and America. Some of the earlier editions, including Elgin’s casts, were found to have preserved more of the sculptural detail that, on one hand was to be scrubbed away from the originals in London (after a mis-guided and over-exuberant British Museum cleaning of them in the 1930’s), and on the other, of those that remained on the Acropolis that had suffered increasing weathering from the worsening acid-rain in the polluted Athens air.

The casting of the London marbles for distribution – back to Athens or to Paris or other major collections was to become a continuous job. Neo-Classical sculptor Richard Westmacott was the first to adopt this work in Regency times, but it was on an ad hoc basis. In the 1830’s the work was outsourced to the revered formatore Pietro Angelo Sarti of Southampton Street. Sarti had long been Westmacott’s assistant and with requests for complete sets of casts being received – notably from the Louvre – and the moulds by then showing their age and needing to be re-made – it was determined that the work should be contracted to him full time; he based the workshop in the basement of the Townley Gallery.

Once it was known that casting of the Elgin Marbles was in production, requests kept coming. Numerous museums across Europe made orders – some were acquired with reciprocal swaps of ancient sculpture. The work fell to the formatore “Lot & Fletcher” mid-century and then subsequently to a rival W.Pink. He oversaw a particularly lively period of co-operative interactions between London and Athens with casts being exchanged, some for restorations and infill work back on the Acropolis.

In the 1860’s, the most revered of formatore Dominico Brucciani took on the role and was permitted to remove the moulds to his workshops on High Holborn – the type-casts stayed at The Museum. On Brucciani’s death on 8th April 1880 the moulds were returned to Bloomsbury and the following year Severio Biagioti, Brucciani’s foreman was appointed by the Trustees to continue the casting work.

In Edwardian times, the remaining set of moulds were in a sorry state. Biagioti’s son Arthur was brought in in order to entirely re-make the moulds. This operation was extremely expensive but deemed worth it. Casting work was still out-sourced to Brucciani’s until 1919 when the firm was subsumed by the Victoria and Albert Museum.

The three casts, available at LASSCO Three Pigeons are from the West Frieze. One is a cast from one of the London panels removed by Elgin, the other two from sections taken down in 1988 and now on display in the Acropolis Museum.

See:

Ian Jenkins “The Parthenon Frieze” 1994, British Museum Press

“The Annual of the British School at Athens” Vol. 85 (1990), pp. 89-114. Pub: British School at Athens