Archived Stock - This item is no longer available

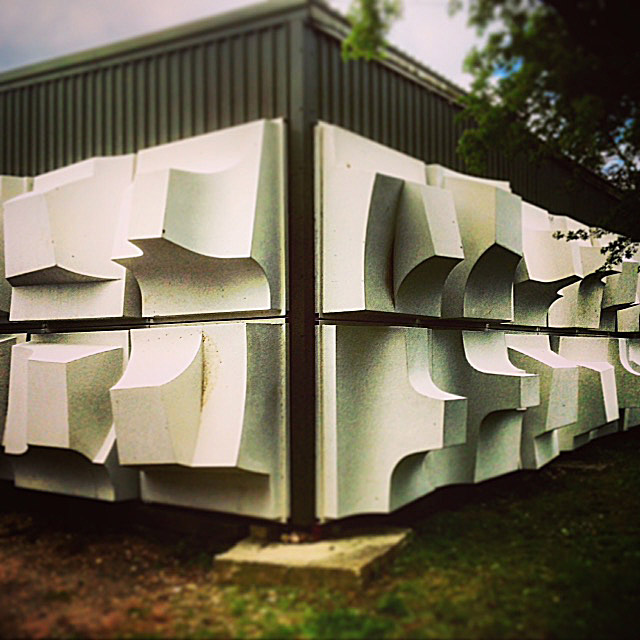

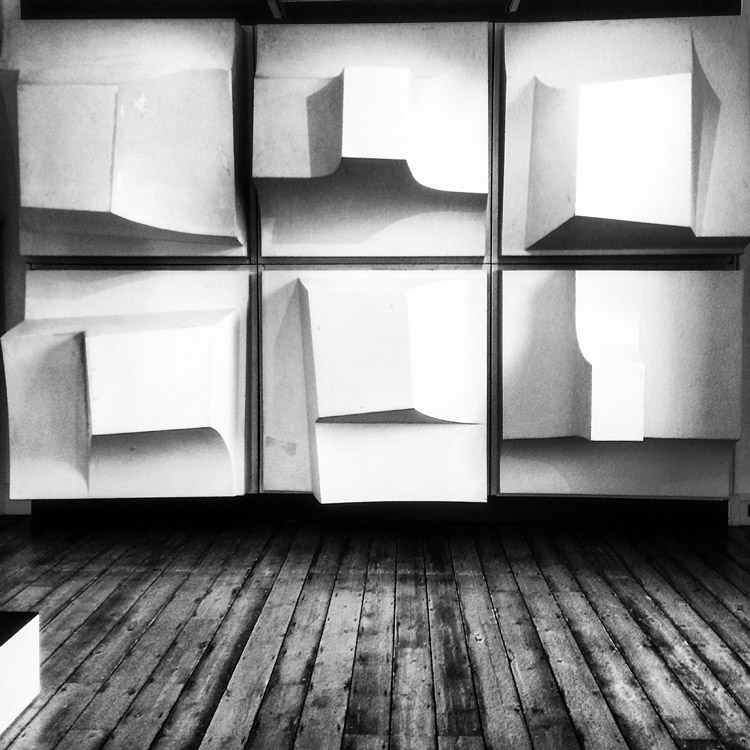

An extraordinary English architectural frieze,

cast as a grid of repeating modular abstract geometric forms in high relief, each pod one of five different casts, and each rotated to create a vast shadow-wall,

SOLD OUT

Out of stock

The frieze was saved from destruction at the eleventh hour by a product designer, local to Falmouth. In recognising the design heft of the piece and failing in a bid to get it listed, he persuaded Sainsburys not to skip it and saved what he could. There are sixty modules saved of the original two hundred – the rest were destroyed (four-high, the original frieze was 6.8m high and 60m long. All sixty are available).

This huge modular frieze was sculpted by Paul Mount in 1984. Mount was at the vanguard of post-war British abstract sculptors. His work is often compared to Moore and Hepworth and there was certainly a flow of ideas – perhaps both ways – evident within that contemporaneous group. Mount’s abstracted figurative works in wrought steel, cast iron and other metals are hotly pursued when any come to market. By the time this late work was created Mount was interested in surface and was looking at unitary construction, repetition and mass production – there must have been a resonance with Carl Andre in that regard. Andre’s pile of bricks, “Equivalent VIII” came to The Tate in 1972. Mount was also not afraid of scale – he had previously created a 200m long frieze for the Swiss embassy in Lagos.

LASSCO acquired the piece after six modules were displayed at Somerset House in the Historic England exhibition “Out There – Our Post War Public Art” – where the frieze, remarkable in that it took the passion of one local entrepreneur to save the work from being entirely skipped, is commented on in reviews such as in the Financial Times.

An Obituary to Paul Mount was written by Michael Bird and appeared in The Guardian 12th February 2009:

“On one hand, the sculptures of Paul Mount displayed the cool geometries of classic modernism; on the other, something much less urbane – more like the firm-footed vitality of Yoruba wood-carving. Mount, who has died aged 86, created a distinctive fusion of these qualities. From his large, wood sculptures of the late 1950s through to his prolific series of abstract, cast-iron and bronze works from the 1960s onwards, to the mirror-like pieces in stainless steel he was preparing for exhibition this year, he combined a passion for formal clarity with an instinct for sculptural power and presence.

Mount’s quiet demeanour belied a prodigious creative output. He also produced architectural designs, painted, published novels and was an accomplished pianist. His sculpture was clearly influenced by the structure of Baroque counterpoint. “I like form for its own sake,” he once remarked, “whether it’s in sculpture, design, music, architecture or painting.”

Mount was born in Newton Abbot, Devon, where his parents were schoolteachers. After attending Paignton School of Art, he studied at the Royal College of Art until he was called up for war service in 1941. A lifelong pacifist, he served in the Friends Ambulance Unit in north Africa and then France, where he stayed on after the end of the war to do relief work. Here, too, he had his first, formative encounter with Romanesque sculpture. Mount and Jeanne Martin, a fellow RCA student, married in Paris in 1946. Returning to the Royal College, he painted portraits and urban landscapes. From 1948 he taught at Winchester School of Art.

In 1955 he took a job in Lagos, Nigeria, setting up an art department at Yaba technical institute. Starting with just an empty building, he designed the furniture and equipment, and recruited students. His work at Yaba – one of the achievements of which he was proudest – led to two contacts that shaped his career. To ensure students learned marketable skills, he employed a wood-carver from Benin. Before long he was experimenting with sculpture – smooth, standing forms in iroko or ebony, reminiscent of Barbara Hepworth. His furniture designs, meanwhile, resulted in commissions from an architectural practice. By 1960 Mount was producing large-scale architectural works, such as his screen wall at the Swiss embassy in Lagos.

The need to create surfaces that deflected the heat while allowing air to circulate – the opposite of modern western architecture’s love of glass and light – helped to form Mount’s sculptural idiom. His cast-iron and bronze works often seemed to project a robust shield around their airy, inner spaces. Another possible African legacy was his refusal to waste anything. Many of his works in metal were fabricated from waste from previous sculptures.

In 1962 Mount returned to England, settling at Nancherrow, near St Just-in-Penwith, Cornwall, where he was to spend the rest of his life. Hepworth was still working nearby in St Ives. Like Hepworth and her sometime assistants Denis Mitchell and John Milne, Mount conceived his sculpture in relation to the landscape, in which it is often sited and probably best viewed. His fascination with machinery, however, led him to develop more angular, industrial forms than other Cornish modernists, closer to those of the Basque sculptor Eduardo Chillida, whom he met in France in the 1970s.

After he stopped teaching, Mount made his living entirely from architectural and public commissions, such as his 1968 Spirit of Bristol in Bristol city centre, and sales of work. He learned to weld from a local blacksmith, and, despite the difficult shift from architectural to gallery scale, was soon exhibiting widely. In 1965 he had his first London show at Drian Gallery and in 1975 he had a solo exhibition at Marlborough Fine Art, both in the West End. In 1976 he and Jeanne divorced and Mount married the painter June Miles. In 1998 the couple had a joint exhibition at the Penwith Society of Arts in St Ives.

In later life, Mount continued to be sought by collectors and to exhibit regularly, including a show at Falmouth art gallery in 2001. By now, however, his kind of sculpture was out of critical fashion. He was one of the last sculptors in a tradition stemming from Henry Moore and Hepworth.

He was one of the last, too, of those British artists whose careers were interrupted by the second world war – who, once free to work again, never really lost their sense of a world to be made anew through art. For Mount, sculpture expressed an essential human dignity. “The way that two shapes relate,” he observed, “is as important as the way two people relate.”

“He is survived by June, and by Martin and Margaret, his son and daughter from his first marriage.

Paul Morrow Mount, sculptor, painter, designer and writer, born 8 June 1922; died 10 January 2009”

The Independent gave the following Obituary by Peter Davies on 16th Jan 1009:

The sculptor Paul Mount exploited the sensual qualities of hard metals, particularly cast iron, bronze and stainless steel, which he used freely to express a vision that ranged from the architectural to the figurative. In common with many distinguished sculptors, Mount began as a painter and continued to make paintings as a vital accompaniment to his three-dimensional work.

Mount’s abstracted sculptures, however, never originated from graphic designs or other cerebral plans, but rather evolved directly from scale models made in makeshift and versatile materials like card, wax and polystyrene. Although the final sculptures have the durable presence of cast or constructed metal, the rhythmic interplay between solid form and open void were created by free manipulation of easily constructed components.

Born in Devon and living in St Just, Cornwall from the early 1960s, Mount worked as an essentially abstract sculptor in an area celebrated by artists like the sculptor Barbara Hepworth. He had no direct professional contact with Hepworth, though he became, along with her former assistant Denis Mitchell, the most prominent sculptor in the region after her death in 1975.

Mount was born in 1922 in Newton Abbot. Educated at the local grammar school, he began art studies at Paignton School of Art and later attended the Royal College of Art in London. During the Second World War, Mount drove for the Friends’ Ambulance Unit in France. A spell teaching at Winchester School of Art after the war led to seven years in West Africa, where he worked as a design consultant on architectural projects in Nigeria.

It was here that Mount found a path as a sculptor. While the power of indigenous tribal sculpture exerted an inevitable impact, Mount’s real sources of inspiration were music and architecture. The characteristic rectilinear movements of his forms reflect his love of music, while the disciplines of the architectural relief called into play subtle formal engineering within often shallow or compact spaces. Mount’s early extended concrete wall for the Swiss embassy in Ikoyi, Nigeria (1960) established what would become a lifelong dialogue with buildings.

His awareness of sculpture as architectural embellishment – informed by the bas-reliefs on the Romanesque churches he visited in France, where he kept a holiday home – led to some notable large-scale sculptures sited in prominent urban locations. Spirit of Bristol (1968) and SkySails (1970), both stainless-steel compositions originally made for sites in the centre of Bristol, evoke the theme of sailing, the abstracted shapes of cut, bent and welded stainless-steel plate “moulded” into a streamlined semblance of boats and taut sails caught in the wind.

SkySails was inspired by a childhood passion for windjammers, which he experienced through a sailor grandfather in Devon. The relief’s current location, pinned to an outer wall of a campus building at Exeter University, reveals a powerful story of materials, an armada of stainless-steel components dancing up the vertical brick exterior of the building.

The lyrical energy of Mount’s sculpture entertained both a literal and metaphorical preoccupation with the theme of movement and dance. Loose, multi-part structures encouraged audience participation in the sense of inviting a rearrangement of interchangeable steel elements. Even with the hard material of steel, Mount made light-hearted mobiles, shaped elements of steel plate attached to axes and moving like rustling leaves in the wind. The romantic overtones of these works expressed natural process and flux and so tempered the impact of hard materials, industrial processes and an abstract language of steel plate.

In many cast bronze and stainless-steel sculptures of the 1980s and 1990s, however, Mount moved his work toward a more “readable” representation of the figure, particularly that of couples embracing or in animated dancing postures. The whimsical stylisation of these dancing forms are perhaps the least sculptural aspect of his work and do not have the earthy gravity of compact, interlocked compositions, cast in bronze or stainless steel, which are inspired by the power of ancient Cornish rock formations of metholithic quoits strewn across the Penwith moorlands.

A quiet, modest man, Mount exhibited both locally and in London and abroad, but his main success lay in the commissions gained through his connections with architects. Forging an ideal working partnership with his second wife, the painter June Miles, Mount also exhibited from home, a sign on the road entering St Just enticing motorists to enter and see a display of their work. This typically West-Country cottage-industry aspect of his enterprise complemented his involvement as an artist member of the Penwith Society of Arts in St Ives and of the Royal West of England Academy in Bristol, the city where much of his metal sculpture was fabricated by the engineer Michael Werbicki.

Mount also sold work to a discriminating Spanish collector whose acquisitions included the cast-iron sculptures Umbrella Man (1984) and Fantasia (1996). Compact and totem-like, these sculptures are also full of movement, curved and linear sections never blocking off space but letting it in as an active part of the overall image.

The deployment of heavy shapes to express outline or encapsulate space reflects the influence of the Spanish sculptor Eduardo Chillida. In contrast to the sculptor-welders David Smith and his English “follower” Anthony Caro, Mount did not use objets trouvés, but rather what he described as objets fabriqués, bits of discarded fragments of metal or of polystyrene cut up and adapted from earlier works.

Such recycling and backtracking highlighted the open-ended, work-in-progress aspect of Mount’s enterprise. For this reason, his sculpture, whether sharply geometric or softer in form, resisted a rigid symmetry. The baroque spirit and moving energy of his work was further enhanced by a use of reflective or pitted and opaque surfaces that broke down the distinction between object and surrounding.

The distinction between Mount’s painting and sculpture lay in the inherent differences of the media. Instead of being plans for sculptures, Mount’s paintings were informed by particular shapes and textures of three-dimensional work. The paintings are indeed reminders of the shared concerns between the two main branches of the plastic arts both within Mount’s work and within that of ambitious abstract artists belonging to the mainstream of the modernist movement.

Recently Viewed Items

-

Tracks and Triggers,

£150Tracks and Triggers,

A Framed chromolithograph by WHO picturing Mr Walter Winans, American marksman, hunter and artist. Author The Art of Revolver Shooting, Winans owned hunting and shooting rights to 250,000 acres in the Scottish Highlands across Glen Strathfarrar, Glen Cannich and Glen Affric. In 1884 he attempted to prosecute a Scotsman, Muirdoch Macrae, for grazing a lamb on the ancestral lands of Clan McCrae but owned in law by Winans. The failure of Winans' prosecution established the right to roam which was a key element in opening British parklands to the public.£150 -

Glazed terracotta tiles,