No products in the basket.

Click and Collect – Please contact us to arrange collection or delivery of this item

Two fine George III Cuban mahogany six panelled doors

c.1775, in the manner of Robert Adam, removed from Charlton Park, Wiltshire, seat of the Earl of Suffolk, a Jacobean House remodelled in the 1770's by Matthew Brettingham the Younger (1725-1803), the two near identical single doors, opposed, removed from "The Large Drawing Room"

each with two square, above two long, and two short rectangular panels, to the obverse each panel is fielded with hand-cut flutes, flowerhead roundels to the corners and carved acanthine lambrequin mouldings around the book-matched flame mahogany field, to the reverse each of the fielded panels conform to the same format but are plain with astragal moulds accentuating the dramatically figured timber; one door has its original gilt-bronze mortise set by Comyn Ching of Seven Dials, each door-knob with a lobed grip and centred with a patera, and a rose with a ribbon-tied plume of feathers and bell-flower chain border - stamped "CHING", the mortice latches in the doors are original and working, as are the hinges, one key survives complete with a later ivorine tag marked "LARGE DRAWING ROOM FROM MAIN STAIRCASE LOBBY"

£24,000 the two

Charlton Park is a large Country Estate in Wiltshire of around 4500acres – it has been the seat of the Earls of Suffolk since early in the 17th Century. John Dryden wrote “Annus Mirabilis” when a guest at the house in 1667.

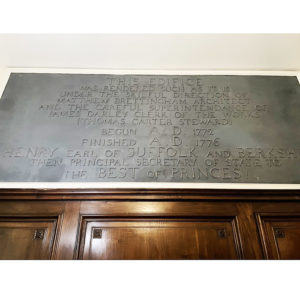

Much later, in the 1770’s, under Henry Howard the 12th Earl, Matthew Brettingham the Younger (1725-1803) was engaged to radically improve and update the house.

Brettingham had spent most of his architectural career working for his father’s accomplished practice and, having based much of his early years in Rome receiving Grand Tourists in general and his father’s client Thomas Coke in particular (Brettingham was involved in the procurement of sculpture for Holkham) – Charlton remains one of only a few houses attributed solely to the younger Brettingham’s designs.

Brettingham operated in circles that saw him granted lucrative appointments such as “Deputy Revenue Collector of The Cinque Ports”. As Howard Colvin tactfully puts it, in reference to Brettingham’s occasional work after the death of his father in 1769, “the income derived from his sinecures seems largely to have relieved Brettingham from the need to develop an extensive architectural practice”.

His project saw the central courtyard roofed over and the hall and surrounding rooms transformed into a spectacular Georgian interior.

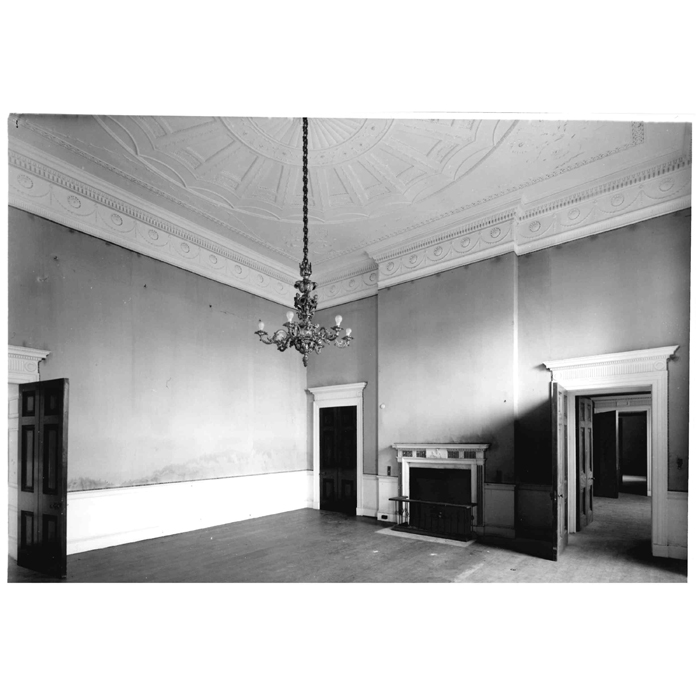

As with so many such houses – despite a restoration in the 1920’s, the middle six decades of the 20th Century saw a painful decline. However, the house was in the vanguard of a drive to re-invent delapidated country houses in the 1960’s and 70’s. In 1975, emulating the work of The Country Houses Association, Christopher Buxton formed “Period and Country Houses Ltd.” and inventively divided the grand house into separate residences which would meet the needs and budget of aspirational folk alongside the Earl who remained in residence. It saved the house but compromises were made. A series of photographs of the house prior to its conversion, and in a sorry state, show the empty interior as Buxton found it.

These twin single doors were removed during those works. They are of the highest calibre. The timber is of the era and quality that only the likes of Gillow were obtaining – we are as yet unable to attribute the doors to Gillow of Lancaster but it remains likely to be their work. They are constructed with thick veneers of spectacularly figured Cuban mahogany laid on a mahogany superstructure. The hinges are set deep into the stile of the door and screwed into place before the veneers were applied. They are 60mm thick and stupendously heavy.