No products in the basket.

28th February 2024

The Philosophers

Introduction:

A wonderful discovery: a pair of 300year old Venetian carved marble plaques – Anthony Reeve, buyer at LASSCO Three Pigeons, tells all:

We’ve bought something rather special. It has taken a bit of work to discover exactly what we have got our hands on, but at every step of the way it has been a voyage of discovery.

It all started on a beautiful sunny day in a house in the New Forest, Hampshire. I was there to look through and buy some very interesting stained glass “hangers” – small round and diamond sections of leaded stained-glass stacked in a box, wrapped in old newspaper. A deal was done, and a cup of coffee was had, before heading-off to the next port-of-call, in Dorset. Before leaving though, as an after-thought, there were a couple of pots and other bits to have a look at, just outside the conservatory. By the fence, was a green plastic box and in it were two carved marble plaques. Each plaque was carved in relief with the profile of a bearded man – and they were beautifully carved too. The back of each plaque had a rusty old peg sticking out. They were slightly green with algae having been sat outside in the plastic crate for some time.

The vendor had said that they, the stained glass and the marble plaques, had belonged to their late grandfather – he had been an antiques dealer. But the time had come to sell them. After the stained glass deal I was a bit spent-out (it had all added up) but a subsidiary deal was done, the bearded men plaques were added to the haul, and off I went.

Back at base, Tom and I started to look into the history of both the plaques and of the antiques dealer that had owned them. We very carefully cleaned the marble. We had a museum display-stand company make some stands so the plaques can either be wall-mounted or securely stood upright. The more we looked at the wonderful carving and the more we looked for comparisons, the better it started to get.

We got some help from The Burrell Collection in Glasgow and found out more about the antiques dealer. Murray Adams-Acton was quite a character. He, it transpires, was one of the most successful dealers in medieval and early English furniture of his day. Together with his business partner Frank Surgey he salvaged and bought extraordinary things and sold them to the burgeoning American museums and elite private buyers found between-the-wars in London. Two of their customers are particularly noteworthy and Murray and Frank devoted much of their careers to helping them build their collections: in Glasgow, Sir William and Lady Constance Burrell and in California, William Randolph Hearst. The story of Murray Adams-Acton is told in Part I below. As it was Murray Adams-Acton who had owned the plaques, we were driven to dig deeper into the history of who might have made them and when.

Simone Guerriero is an Art Historian in Venice, specialising in the sculpture of the Veneto between the 17th and 19th Century. He has been involved in exhibitions of such sculpture and is widely published on the subject. We were stuck with our own research – we asked him to produce a report on the marble plaques. His report is reproduced below in Part II. It is wonderful to see how he arrives at his attribution, the tell-tale details and marks and influences and styles that enable him to put our sculptures alongside other works. He demonstrates exactly whose hand, with a “snappy and nervous character” chiseled out these plaques over 300 years ago: he firmly attributes the two plaques to the Venetian sculptor Francesco Penso, known as Cabianca, (1666-1737). The plaques most likely date to around 1710.

He explains what the image of the Philosophers – for that is who they are – meant to Venetians of the time and how it was a canon, a cult almost, which a number of Cabianca’s contemporary sculptors also explored.

Guerriero is able to detail much of Francesco Cabianca’s career and points to his work which can still be found today – in Venetian churches, Colleges, the Venice Arsenal and, after a series of busts he executed for Tsar Peter the Great, in Pavlovsk Palace near St. Petersburg. The work is fabulous – one cited commentary (by Camillo Semezato in 1966) opines about one of Cabianca’s reliefs that: you will not find “so much rhythmic continuity in any other Venetian sculpture of this period [with] so much skill in composition”. Guerriero himself concludes that “Cabianca was therefore certainly one of the greatest protagonists in the panorama of Venetian sculpture in the decades at the turn of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries”. The report is translated and reproduced, in full, in Part II below.

The plaques are now available to purchase at LASSCO Three Pigeons – they can be seen on our website here. If you would like to receive this LASSCO News article as an email to read later, please contact 3pigeons@lassco.co.uk

Part I:

Murray Adams-Acton – Architectural Salvage hero: a brief history

LASSCO acquired these beautiful relief carvings from a descendant of Murray Adams-Acton (1886-1971); they were in his private collection. Adams-Acton is remembered as a flamboyant character who had a notable career in the world of interior design and antiques, mixing in the highest echelons of London society.

Adams-Acton’s early working life, in Edwardian London, was at White Allom Ltd – Sir Charles Allom’s (1865-1947) design firm that was running prestigious interior decoration and design projects on both sides of the Atlantic. They worked for fabulous clients – including for the Frick family with the creation of the Frick Museum, and for the Crown with the new extension to Buckingham Palace. It is likely that it was at White Allom that Adams-Acton first fell-in with Frank Surgey (1893-1974) who worked at both the London and New York offices as assistant to Sir Charles. Adams-Acton’s drawings and designs from this time were exhibited at the Royal Academy in London between 1909 and 1915.

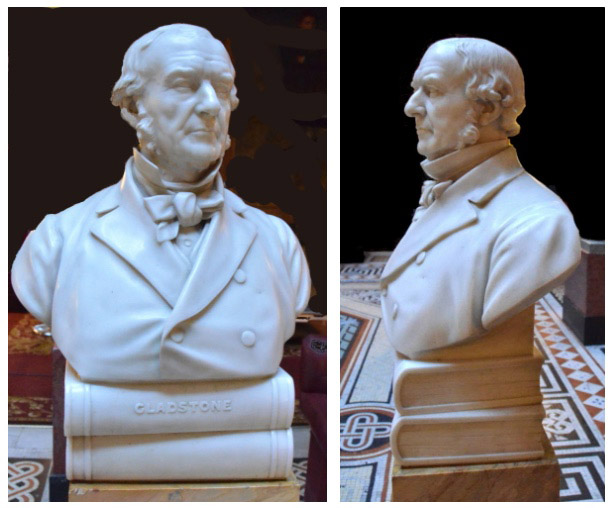

Murray’s father, John Adams-Acton (1830-1910), was a talented sculptor. His portraiture in marble was held in high regard. Having won the Royal Academy’s Gold Medal for sculpture in 1858 he had spent some years in Rome on the resultant travelling scholarship studying under John Gibson. He thereafter submitted numerous busts and statues to the Royal Academy shows, as well as for public commissions, both in England and the Empire. William Gladstone sat for the sculptor on at least two occasions and they became great friends; Gladstone was to be Murray Adams-Acton’s godfather (his full name was in fact Gladstone Murray Adams-Acton). Other sitters included, Benjamin Disraeli, Charles Dickens and Pope Leo XIII. In 1910, John Adams-Acton sadly died from injuries sustained in a motor-car accident – an early victim of a new and growing phenomenon.

The house where Murray grew up in St. John’s Wood – he was the fourth of five children – was known for social gatherings of all the mover-shakers of the day. His Scottish mother Marion, daughter of the 11th Earl of Hamilton, was a successful author of children’s books under the name Jeanie Hering and seemed to have provided a social hub to many in artistic circles.

When war broke out in 1914 Murray, by then aged 29, joined up with the Scots Guards and during his service was to rise through the officer-ranks to Colonel. His former colleague Frank Surgey meanwhile had joined the Air Flying Corps and had spent the war years heroically engaging in aerial dog-fights over Flanders, surviving a number of crash landings.

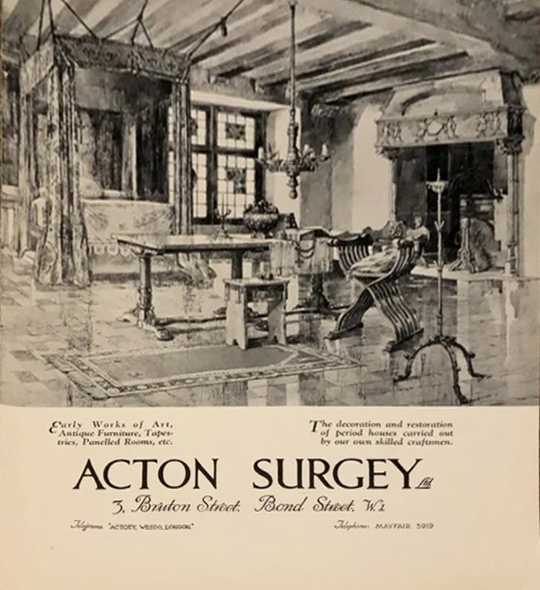

After the war, Adams-Acton and Surgey joined forces and formed “Acton Surgey”: dealers and consultants specialising in medieval art, sculpture and old English furniture. For years, Adams-Acton wrote numerous articles on decoration and old furniture for ‘Apollo’ and other magazines such as ‘The Connoisseur’, publications that Acton Surgey were to regularly advertise in. He became a Member of the Architectural Committee of the Royal Academy, and a Member of the Society for the Protection of Ancient Cottages. He wrote ‘Domestic Architecture & Old Furniture’[i] demonstrating his expertise on the subject; his particular speciality was to become old English linenfold panelling[ii], and the company regularly dealt in the selling of entire salvaged rooms. Their stock, initially, was showcased at their gallery at 1 Amberley Road in Paddington, as well as a premises in Crews Hill, Sussex.

In “Moving Rooms – the Trade in Architectural Salvages” John Harris keeps pace with the sales that Acton Surgey were involved with at a time “…when American museums were thirsting for English rooms”. They offered the “Hayes Grange” room extracted from Sir Edmund Davis’ house in Lansdowne Road to the V&A in 1926[iii]. They offered the Great High Chamber from Gilling Castle, Yorkshire to Philadelphia Museum of Art in 1929[iv] and oak panelling, dated 1529, thought to have been from Red Lodge, West Wickham, Kent[v]. In the same year they handled the sale of Robert Adam’s Drawing Room from Lansdowne House on Berkeley Square to The Metropolitan Museum of Art in Washington DC, selling it for $10,904, and the Dining Room which went to Philadelphia in 1933[vi]. They bought a George II interior from St Margaret’s Place in King’s Lynn and sold it to the new Nelson Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City in 1931. And Robert Adam’s “palm tree tea pavilion interior” from Moor Park Hertfordshire – sold in 1933 to a private buyer to install in a house thought to be in Virginia or Maryland.[vii]

By 1930 the shop was at 3 Bruton Street, off Bond Street. Clients could also see stock displayed at Weycroft Abbey, near Axminster, Devon. Those clients included Sir William Burrell (1861-1958), the wealthy Glaswegian shipping merchant and art collector, and the publisher William Randolph Hearst (1863-1951), the most voracious buyer of Architectural Salvage the world has ever known.

Sir William Burrell had bought Hutton Castle, Berwickshire in 1916 and having had it extended after the war, finally moved-in in 1927. Acton Surgey were engaged by Burrell to furnish the castle – a project that was to last for seven years – their final invoice coming in at £58,000.

The Acton Surgey visitors’ book from this era is extraordinary – the family still has it. On one page alone it is signed by Constance Burrell, William Burrell, Duke of Rutland (of Haddon Hall), C.Reginald Grundy (the editor of The Connoisseur), William Randolph Hearst and Sir Joseph Duveen. On another page there are two signatures alone – “Mary R, 8th July 1932” and “Victoria Forester”; Queen Mary (accompanied by her Lady-in-waiting) was an expert in ceramics and early furniture.

The two dealers are usually described as flamboyant, Adams-Acton as a “flamboyant extrovert”. They were accomplished yachtsmen, a habit no doubt learned from Charles Allom and his racing yacht “Istria”.[viii] Frank Surgey was reputedly a remarkable shot too and with his own Holland & Holland’s had attended shoots alongside George V on a few occasions (as well as racing against him in the Solent aboard “Britannia” in Allom’s “White Heather”).

When war broke out again, Adams-Acton returned to his old regiment in Inverness, only to later receive the news that his shop in Bruton Street had been completely flattened in the Blitz. He recalled that ‘nothing was left, documents, tapestries etc., went up in smoke’.[ix] Surgey meanwhile moved to Blackburn in Lancashire and ran a factory making aeroplane parts for the Ministry.

Before the war Acton Surgey had been supplying Hearst as he exuberantly kitted-out St Donat’s Castle with Architectural Salvage from across the UK and Europe; the work was overseen by Sir Charles Allom, Murray and Frank’s former boss. On Hearst’s death in 1951 they were now contracted, as agents to Hearst’s London-based “National Magazine Company”, to handle the disposal of his vast acquisitions held there. It was a mammoth task – Adams-Acton described “huge piles of crates, temporarily roofed in around the castle, which have come from all parts of Europe, & much which was sent to America and then sent back here again!” [x]

Between 1952 and 1956 Adams-Acton was again acquiring numerous architectural salvages for Sir William Burrell; this time it was more “architectural” with stone gothic entranceways and medieval architectural embellishments for inclusion and incorporation into the new museum that was to be built to house The Burrell Collection. Sir William had gifted his collection of 6000 items to the City of Glasgow in 1944 (he had added another 3000 before he died in 1958) and had bequeathed £400,000 to build the museum. Burrell stipulated that the museum was to be designed by Frank Surgey and, in parts, to exactly replicate the interiors of the rooms that Acton-Surgey had furnished at Hutton Castle.

“ And I am very anxious that Mr Frank Surgey, Paschoe House, Bow, near Crediton, North Devon, whom I consider to be better fitted for the work than any other person in this country, should draw out the plans et cetera for the Museum for the consideration of my Trustees and the Corporation; And I earnestly hope that the Corporation will concur in my suggestion which I have very much at heart; And I suggest that Mr Edwin Surgey, A.R.I.B.A. be associated with his father in the preparation of the plans should Mr Frank Surgey desire it; And I further suggest that the Museum should be as simple and inexpensive as possible but specially designed to house the Collection and with suitable offices connected therewith”[xi].

Decades went by before progress was made, as Burrell’s stipulations concerning the location of the museum proved restrictive. Ultimately, with a suitable site secured, the Trustees opted for the museum design to be put out to competitive submissions in 1971 (and chose that by Barry Gasson). The Museum was finally opened in 1983.

The room sets from Hutton Castle, that Burrell had proposed were recreated by Surgey and his architect son, incorporated a series of 15th Century stained-glass roundels. It transpires, that the stained glass that LASSCO bought in a box in the house in the New Forest, was a continuation of that series; those not acquired by Burrell, Adams-Acton held on to.

As for the relief-carved Philosopher plaques, we don’t know how they came to be in the private collection of Murray Adams-Acton. If the sculptures were sourced in Venice it is known that Frank Surgey holidayed there with his wife in 1930 – but this is surely incidental. We have found no other leads to them – photographic or otherwise – nor indeed to any other baroque sculpture; it does not seem to have been Acton Surgey’s area – it was not what they dealt in.

It is much more likely however that John Adams-Acton, his father, had left the Philosopher carvings to him; it is entirely plausible that a Royal Academician portrait sculptor of marble, who had spent his early career in Rome, would have had them in his studio – treasured pieces for inspiration[XII]. Murray Adams-Acton was in his twenties when his father died – if that’s how they came to be in his possession, they would have been personal to him; we know he never parted with them. Either way, one wonders if either John Adams-Acton or his son Murray ever knew, that the Philosopher plaques were carved c.1710, by Francesco Cabianca of Venice. It’s time for Part II.

Acknowledgements: LASSCO would like to thank: Simone Guerriero for his research – published here for the first time (see Part II below), Tim Stothert for encouragement and advice, Kira d’Alburquerque and Jenny Saunt at the V&A for their time and recommendations, and Fiona Cairns at the Burrell Archives for helpful correspondence.

Notes to Part I

[i] Murray Adams-Acton, ‘Domestic Architecture & Old Furniture’ G. Bless, London, 1929.

[ii] He was to publish a two part study of “The Genesis and Development of Linenfold Panelling” in Connoisseur June 1945 pp25-31 and 80-86.

[iii] See John Harris “Moving Rooms” Yale 2007 pp110-114 The Hayes Grange Room had been salvaged by Hindley & Wilkinson, and previously been offered to the V&A in 1908, before they sold it to Davis.

[iv] Harris, Ibid, p165

[v] Harris Ibid, p.174

[vi] Harris, Ibid, p.243

[vii] Harris, ibid, p240

[viii] Allom became a partner in the Camper & Nicholsons boatbuilders who designed and built the innovative “Istria”. Allom went on to form “The Gosport Aircraft Company” with Charles Nicholson developing flying boats for the Government from 1914-20.

[ix] Letter from Adams-Acton to William Wells, 10 October 1958, Burrell Collection Archive.

[x] Letter from Adams-Acton to Dr Hannah, Glasgow Museums, 28 November 1952, Burrell Collection Archive

[xi] Recorded in Acts of Scottish Parliament that were added to the statute with amendments in 2013

[XII] With the picture of John Adams-Acton bust of Disraeli here pictured there is a lead we might still have to follow. Disraeli was a collector of Italian sculpture and Sir Philip Rose gave him a set of relief carved portrait plaques by Orazio Marineli (), a contemporary Venetian sculptor to Cabianca. They were dispersed in the Christies “Disraeli Sale” of 1881 – sold to Park Place on Remenham Hill, Henley. They were eventually bought by the Art Fund to be displayed at Disraeli’s “Hughenden Manor” where they can be seen in the Dining Room today. If the Marinali plaques were released onto the market by Disraeli’s brother through Christies, just at the time that Adams-Acton (Snr) was completing his bust of the recently deceased Prime Minister – there might have been others in that collection, such as the Philosopher plaques. It’s a long shot, but research continues.

Part II:

Report by Simone Guerriero, February 2024:

Francesco Penso, known as Cabianca (Venice 1666-1737)

Profiles of Philosophers

Reliefs, Carrara marble

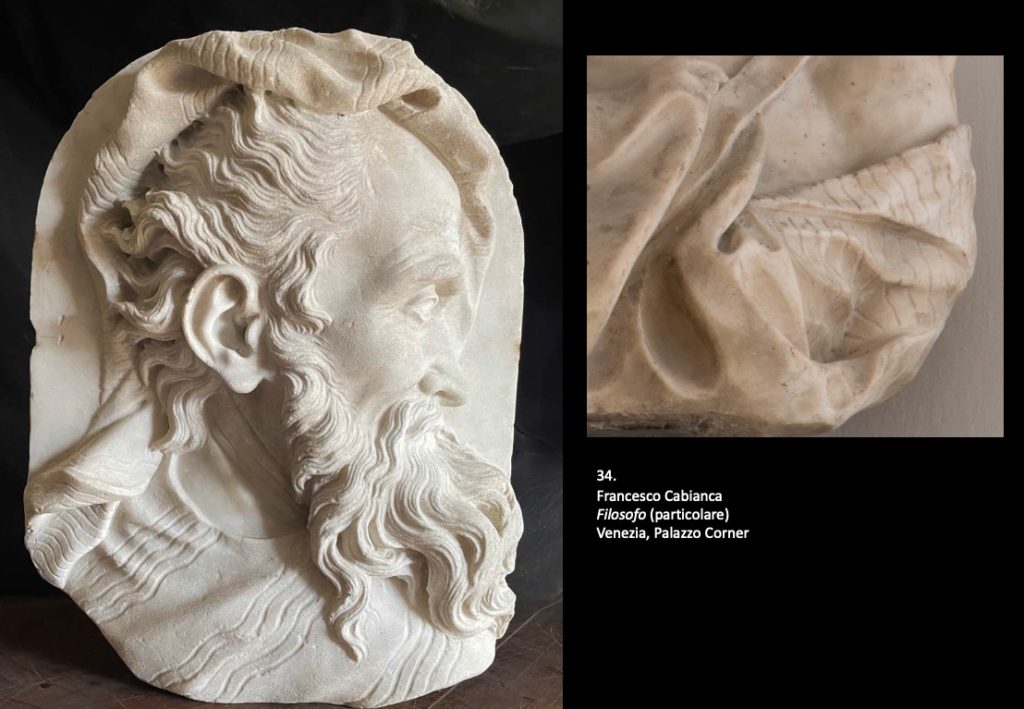

In these two masterfully carved heads in high relief in Carrara marble, each portraying a man in profile in old age, with a hirsute face and head covered by a mantle, a pair of representatives of that lineage of philosophers who, depicted in painting as well as in sculpture, populated art collections in Venice at the turn of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries is recognizable.

Usually, as in our case, these figures do not show specific iconographic attributes that would help us identify their precise identity in the roster of ancient thinkers: more generically, their features often reveal a stern, pensive attitude and they are almost always bearded elders, displaying an intense but detached gaze, in keeping with the traditional iconography of the philosopher.

The images of philosophers, who represent introspective thinking aimed at understanding what humanly matters (love, friendship, knowledge), invited by their presence to recognise the vain and frivolous nature of many aspects of worldly existence and to be reminded of the fragility of life, the transience of earthly things. Philosophy as an antidote to Vanitas.

Beginning in the 17th century in particular, depictions of ancient thinkers became the object of particular interest throughout Europe, on the part of patrons and collectors, and thus an almost constant presence within collections, on a par with other subjects equally referable to the theme of Vanitas, such as St. Jerome in the desert – with whom the motto “vanitas vanitatum et omnia vanitas” is associated – and Magdalene in meditation, the Putto with skull or intent on blowing soap bubbles.

However, in some cases, the possession and exhibition of an ideal portrait of an ancient philosopher absolved, as far as its meaning was concerned, to an exaltation of libertas philosophandi, in opposition to dogmatic doctrine and the undue use of auctoritas operated by the Catholic Church, claiming a sincere and dispassionate love for free philosophical research.

Venice – the sphere of origin to which our pair of profiles belongs – will constitute in the seventeenth century, and then again in the following century, one of the main centres of production of these images, playing a fundamental role in the propagation of this sort of cult for the exponents of ancient thought, which later, in the collecting sphere, will take on the characteristics of a true fashion.

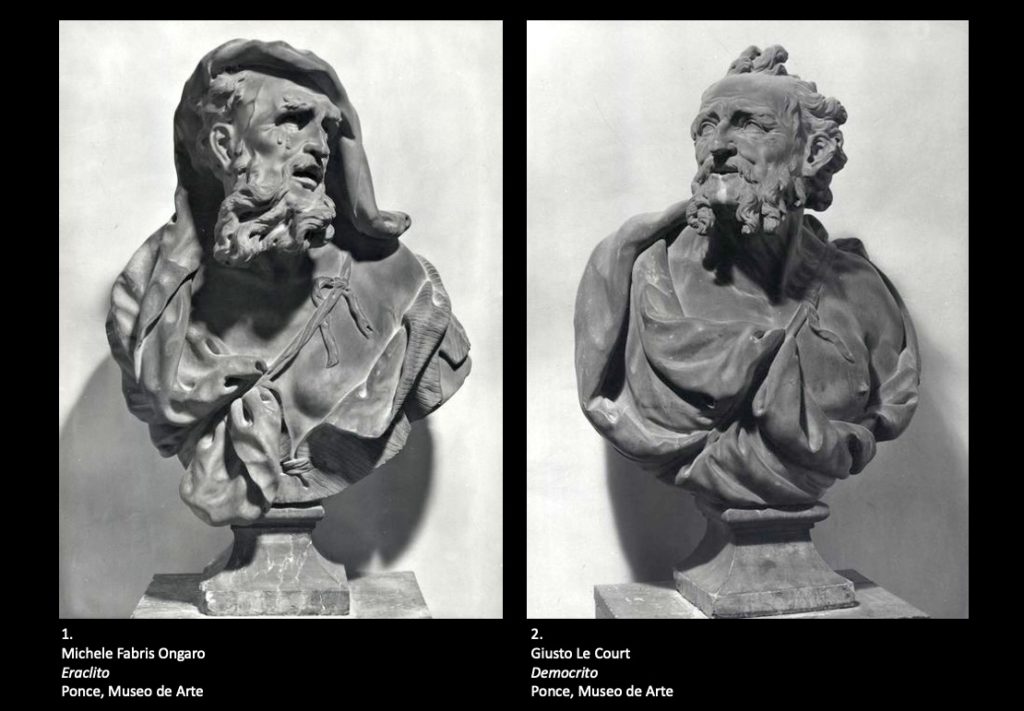

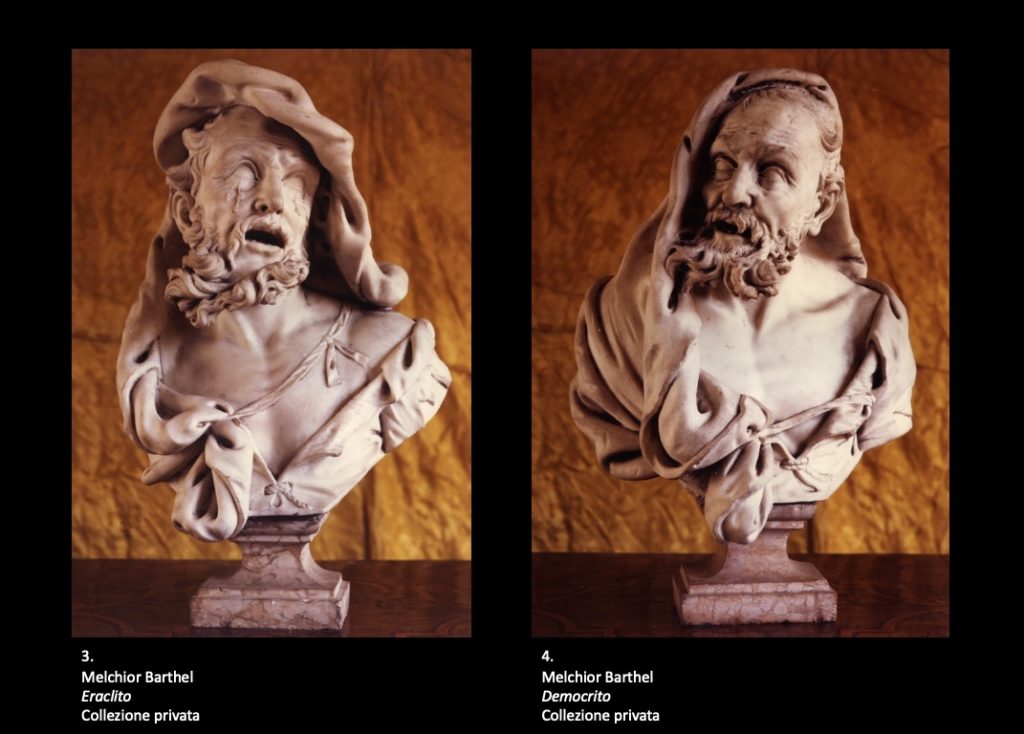

The two images carved in marble that are the subject of this study should be directly linked precisely to the great fortune that the depiction of ideal portraits of ancient philosophers had in Venetian sculpture, especially in the second half of the 17th century, a fortune testified by the recurring presence of these subjects in the inventories of the collections of the time and by the many works that have come down to us. Among the earliest and most important examples that can be mentioned here are the busts depicting Heraclitus and Democritus, respectively by Michele Fabris known as Ongaro (c. 1644-c. 1684) and Giusto Le Court (1627-1679), from Palazzo Mocenigo in Venice and now in the Museo de Arte in Ponce (figs. 1-2), which constitute the prototype for other pairs of marbles dedicated to the same theme of the contrast between the weeping philosopher and the laughing philosopher faced with the vicissitudes of earthly life, such as the examples made by Melchior Barthel (1625-1672) now in a private collection (figs. 3-4).

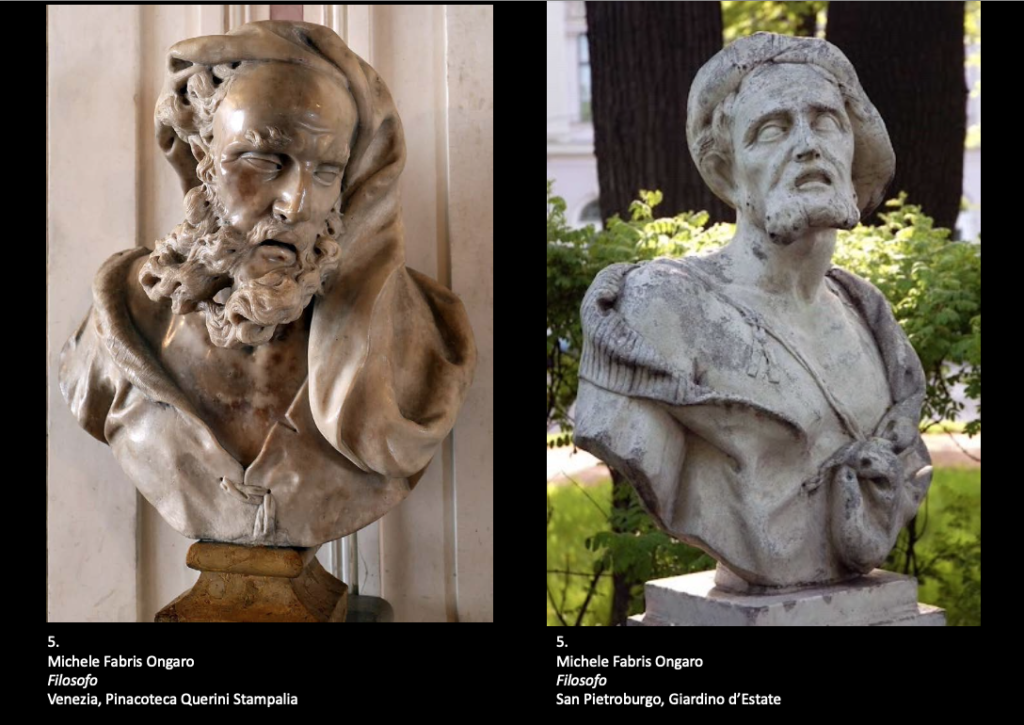

The greatest representative of this genre of sculptural production devoted to ideal portraits of ancient thinkers was certainly Ongaro, who is responsible for a vast number of works depicting philosophers. Among all of them, it will be worth mentioning the celebrated series of marble busts (fig. 5) arranged along the walls of the portego of the Venetian Palazzo Querini Stampalia (now the Pinacoteca Querini Stampalia), or, again, the busts featured in the series of marbles representing philosophers and Olympian gods that was purchased in Venice around 1717 by Count Savva Raguzinsky for the collection of Tsar Peter the Great and then placed in the Summer Garden in St. Petersburg (fig. 6)[1].

Among the many other Venetian sculptors who devoted themselves to the theme at the turn of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries – remember Giovanni Bonazza (1654 – 1736) or Giuseppe Torretti (1664 – 1743), just to name a couple of the most celebrated artists of the time-there is also Francesco Penso known as Cabianca, to whom should be referred, for obvious stylistic reasons, our two reliefs that were originally intended to be set on a wall, as confirmed by the presence of a wrought iron bar, set in the marble with cast lead, that protrudes on the back of each relief for the purpose of anchoring it to the wall.

The name of Cabianca as the author of the two works is immediately suggested by the snappy and nervous character with which the sculptor outlines the flow of the long beards and shaggy hair, a character that also finds a correspondence in the way he arranges the folds of the mantle and highlights the physiognomic and anatomical features of the two elderly philosophers[2]. The attribution to this important Venetian artist is proven-as will be seen later-by the precise comparisons established with some works of similar subject matter made by Cabianca during his career.

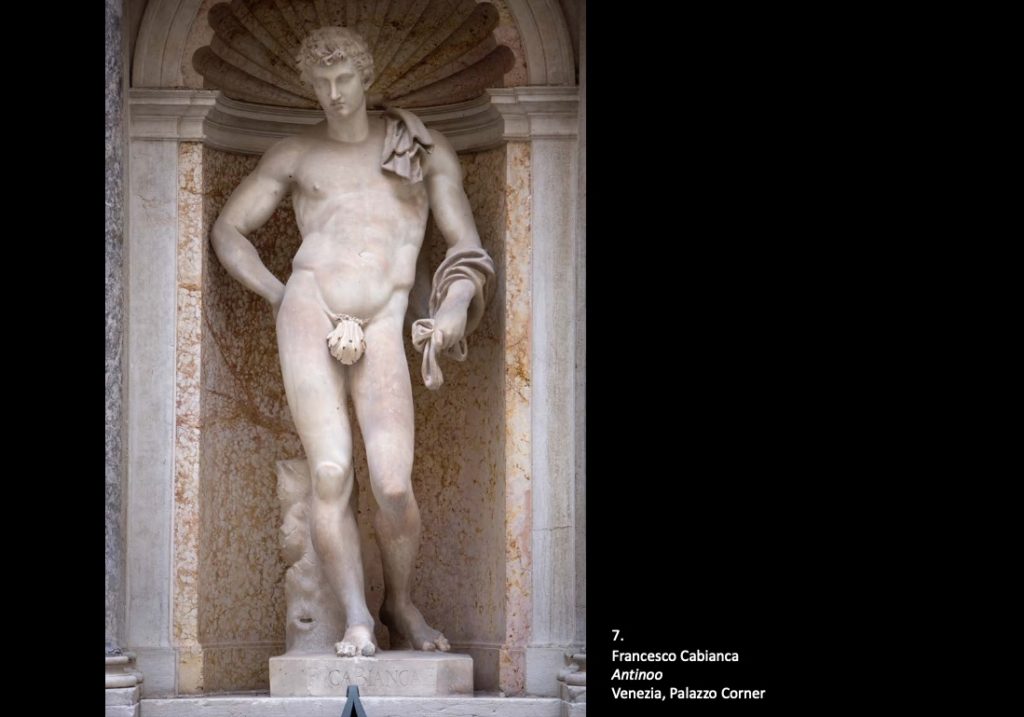

His career that probably began with a commission of particular prestige: according to the Venetian architect and erudite Tomaso Temanza – who, with his “Zibaldon” composed in 1738, is the artist’s first biographer -, the first work he executed as an independent sculptor would be the Antinous (fig. 7), signed “F.co CaBianca F.,” a copy of the famous statue of the Belvedere in the Vatican[3].

Temanza informs us that the very elegant image of the young lover of Emperor Hadrian was ordered from Cabianca by an envoy of Louis XIV, who had been commissioned by the sovereign to ask some important masters in the Serenissima Republic for copies of ancient statues to be made in marble and destined to decorate the parks of various residences of the French crown; but, due to delays in the delivery of the work, the sculpture did not leave for Paris, remaining in Venice in the artist’s workshop, where it was eventually purchased by the Corner nobles who placed it in the large niche in the courtyard of Palazzo Corner on the Grand Canal, where it still stands today[4].

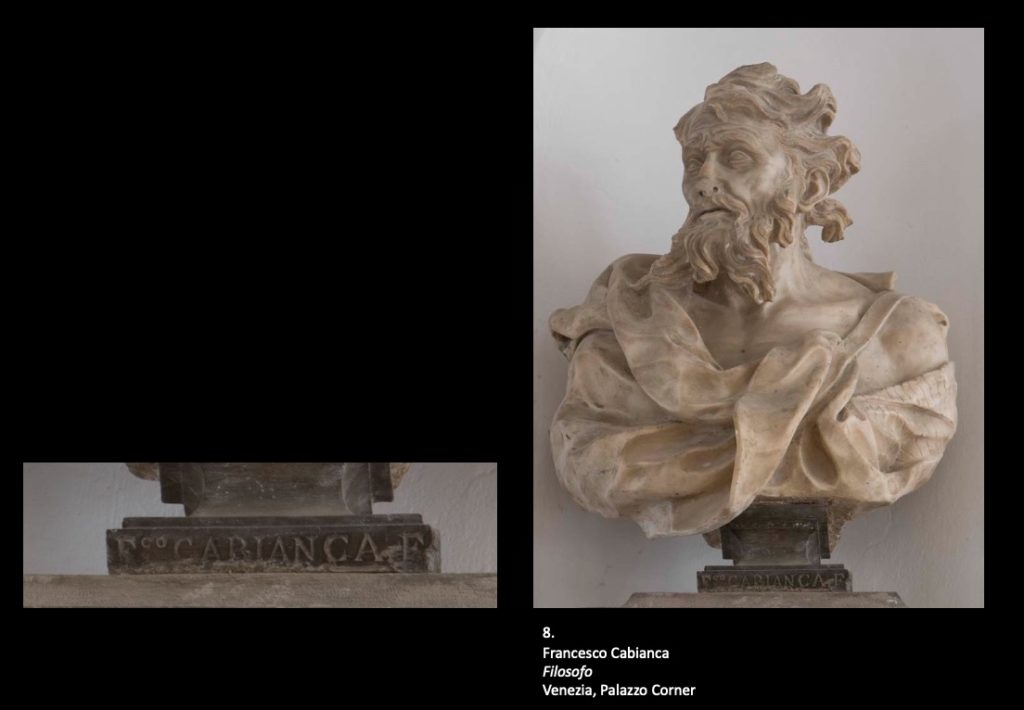

The Corners probably on that same occasion also purchased some busts carved in marble by the artist, which are still preserved in the portego of the palace, including a bust of Philosopher signed “F.co CABIANCA F.” (fig. 8)[5], a work that constitutes a first secure term of comparison for assigning the two relief profiles under consideration to the Venetian sculptor.

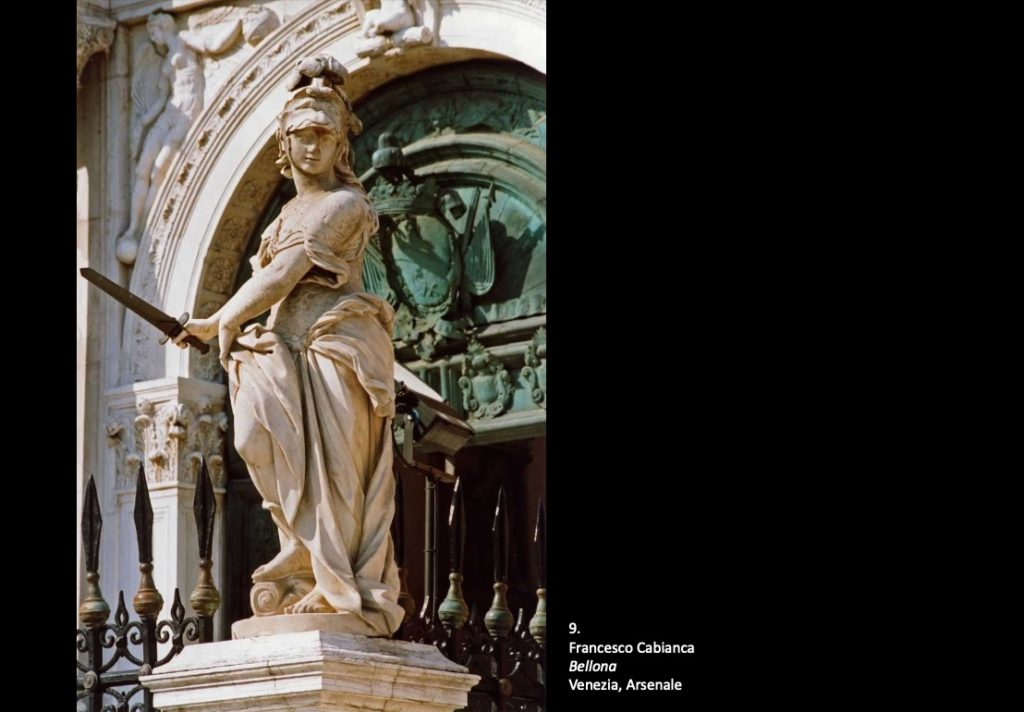

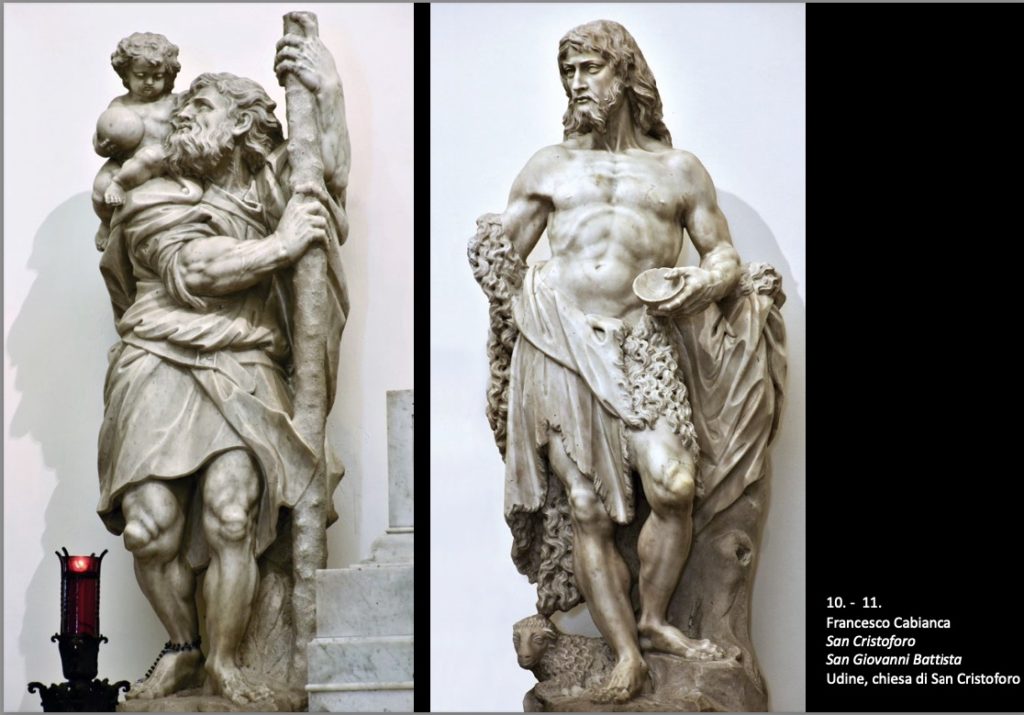

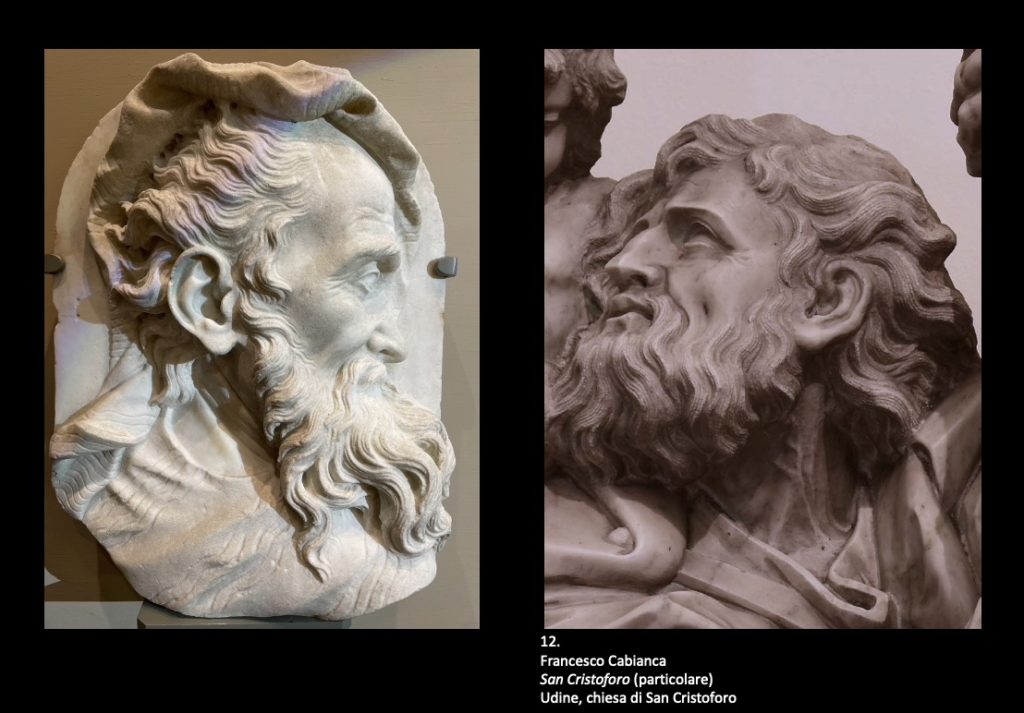

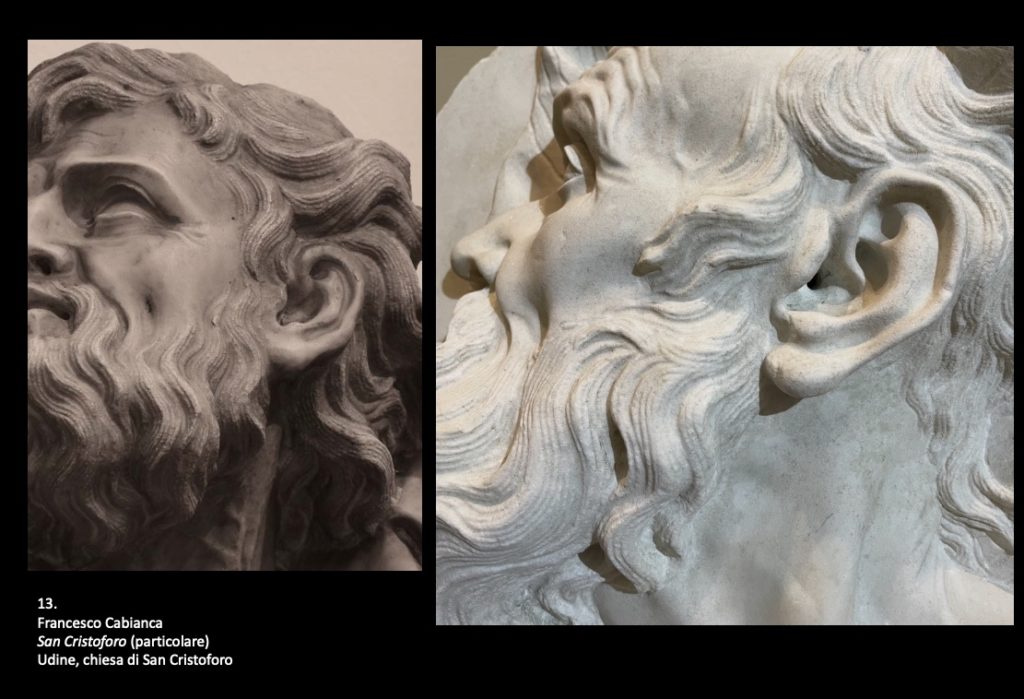

Some time later, by 1692, Cabianca received another commission of undoubted prestige: together with “the most conspicuous authors of our times”[6] he was in fact involved in the creation of the sculptural decoration for the enclosure of the land entrance to the Arsenal commissioned by the Republic, which entrusted him with the execution of the figure of Bellona (fig. 9), a work also signed. In the same year, as Temanza also recalls, he worked on a series of bas-reliefs with naval battles for the monument to Doge Francesco Morosini, which, however, was never installed. Toward the end of the seventeenth century the artist was already regarded as one of the most renowned Venetian sculptors and as such is in fact mentioned by Father Vincenzo Coronelli, official cosmographer of the Serenissima Republic, in his guide to the city of Venice published in 1697[7]. It was around that year that Cabianca made the statues of St. John the Baptist and St. Christopher for the church of San Cristoforo in Udine, works significant for their high quality of form and execution (figs. 10-11). The face of St. Christopher is of particular interest to us because, when examined closely, it shows the same stylistic features as the two Philosopher profiles, as we can observe, for example, in the workmanship and arrangement of the long locks of the beard and hair (figs. 12-13) or in the way the face is hollowed out under the cheekbone (fig. 13).

In 1698, on the advice of a doctor, to cure a venereal disease, the sculptor sailed from Venice to Dalmatia, where he stayed for about ten years, living in this part of the Serenissima’s dominion, but also in Cattaro (Kator) and in the neighbouring Republic of Ragusa (Dubrovnik), many of his works, mostly of modest quality having been made with extensive use of the workshop.

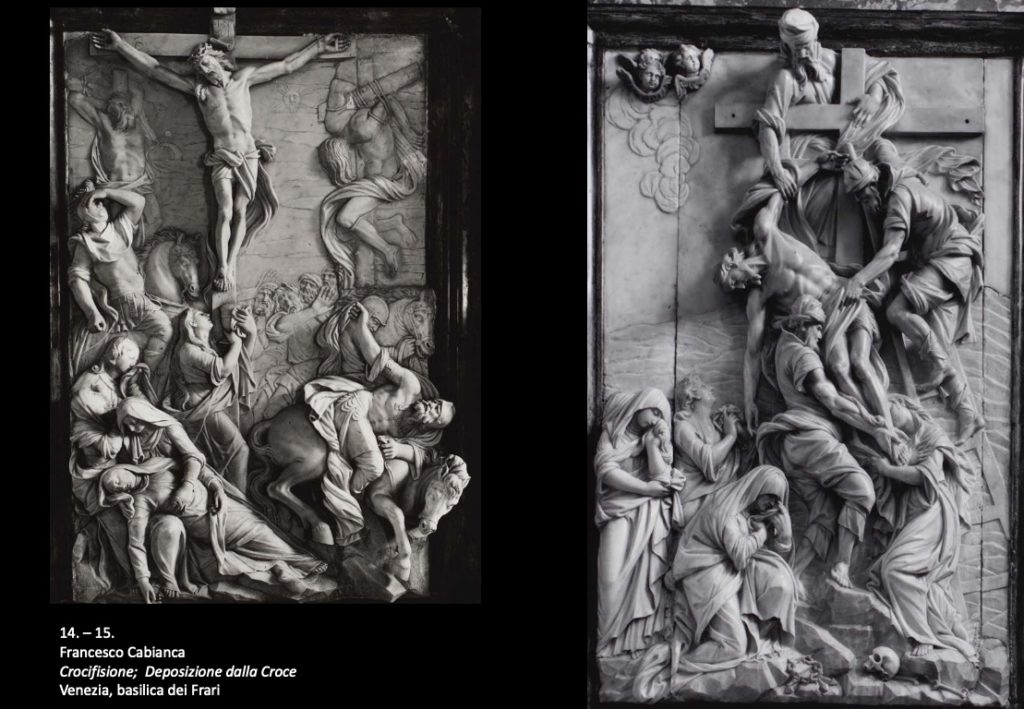

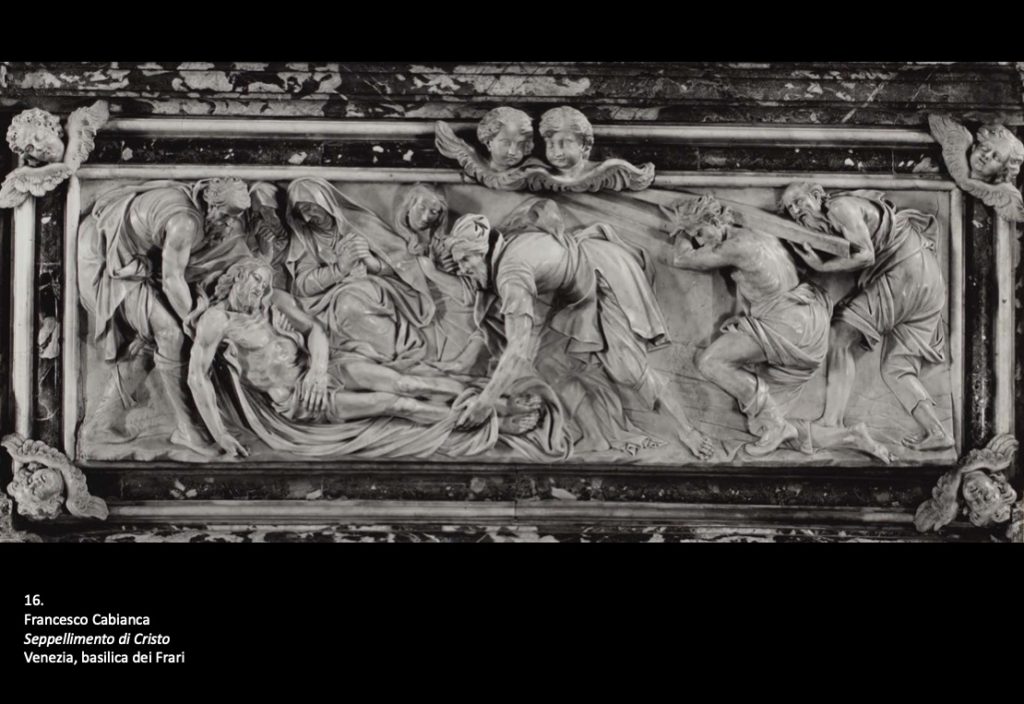

Returning permanently to Venice in 1708, Cabianca devoted himself until 1714 to a series of important works for the Franciscan convent of the Frari: from the magnificent reliefs for the altar of the Relics in the sacristy of the basilica, put in place in 1711, to the statues and groups of figures for the cloister of the Trinity. In the three main panels of the Altar of Relics, true ‘marble paintings’ with the scenes of the Crucifixion and collection of Christ’s precious blood (fig. 14), the Deposition from the Cross (fig. 15) and the Burial of Christ (fig. 16), the sculptor’s great mastery is expressed.

These works represent-as Camillo Semenzato rightly observed in 1966-one of the highest points of Francesco Cabianca’s activity, and one does not find “so much rhythmic continuity in any other Venetian sculpture of this period, so much skill in composition” to such an extent that “we cannot help but stand in admiration before the drawing that runs through the scenes tying together the movement in a continuous chain of articulations, falls, and rebounds”[8].

A few years later the Venetian artist participated in the sculptural decoration of one of the monuments of the Manin family in the cathedral of Udine[9].

Between 1716 and 1717, like many other Venetian sculptors of the period, Cabianca was engaged by Tsar Peter the Great, a commission to provide sculptures for the Summer Garden decoration in St. Petersburg, including several of emperors and the statues of Vertumnus, Pomona, and Saturn (figs. 17-18)[10]. Shortly after 1718 he sculpted the large bas-relief depicting the Martyrdom of Saints Simon and Judas that adorns the pediment of the facade of the church of St. Simeon ‘Piccolo’.

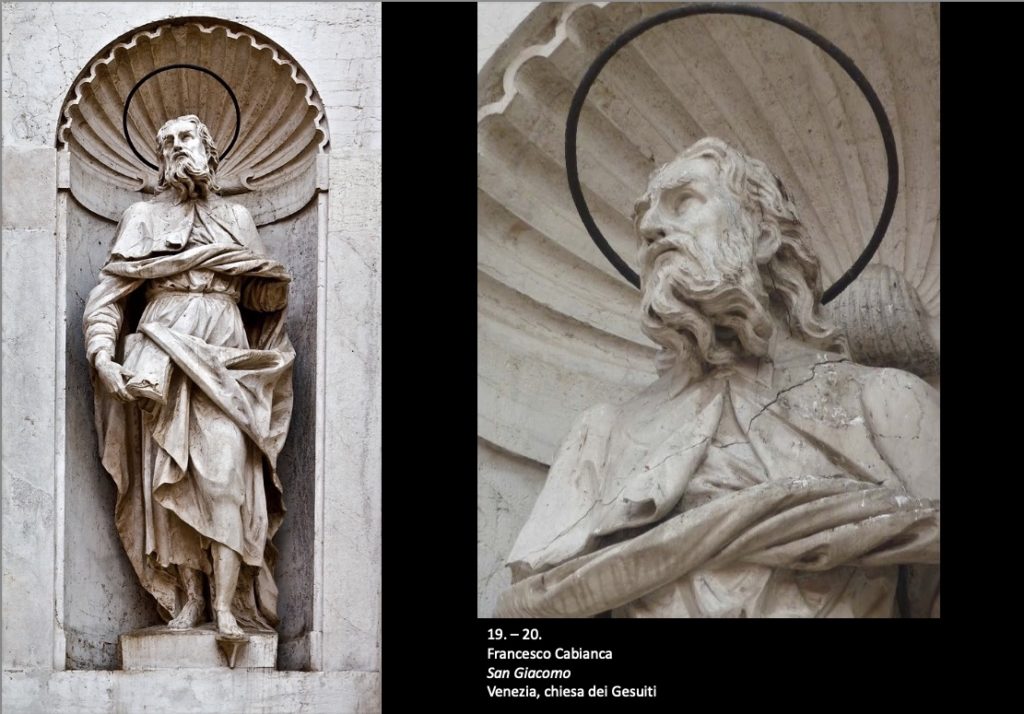

Around 1725 dates one of the last and most significant undertakings in which he participated: for the facade of the Venetian church of the Jesuits he made figures in Istrian stone depicting St. James the Greater (figs. 19-20), St. Andrew, and St. John the Evangelist. The latter subject would be reworked by him in the imposing marble statue of St. John the Evangelist (fig. 21), c. 1730, for the altar of the main hall of the Scuola Grande dedicated to the saint of the same name. In the early 1930s, Francesco closed his Venetian workshop and moved to Gorizia, but his career had now come to an end. In the Zibaldon, after calling him a “distinguished Venetian sculptor,” Temanza informs that the artist passed away in 1737, at the age of 72, “in the most extreme misery”[11].

Cabianca was therefore certainly one of the greatest protagonists in the panorama of Venetian sculpture in the decades at the turn of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, not only in the sacred sphere and in relation to major public enterprises but also on the side of sculptural production destined for private collecting; an activity, this, that he carried out prolifically as recent studies have been able to document thanks to the discovery of a significant number of new works. The artist tried to respond as best he could to the solicitations of the patrons and collectors of his time who came to him, among whom might have included patricians, merchants, and citizens among the wealthiest and most sensible.

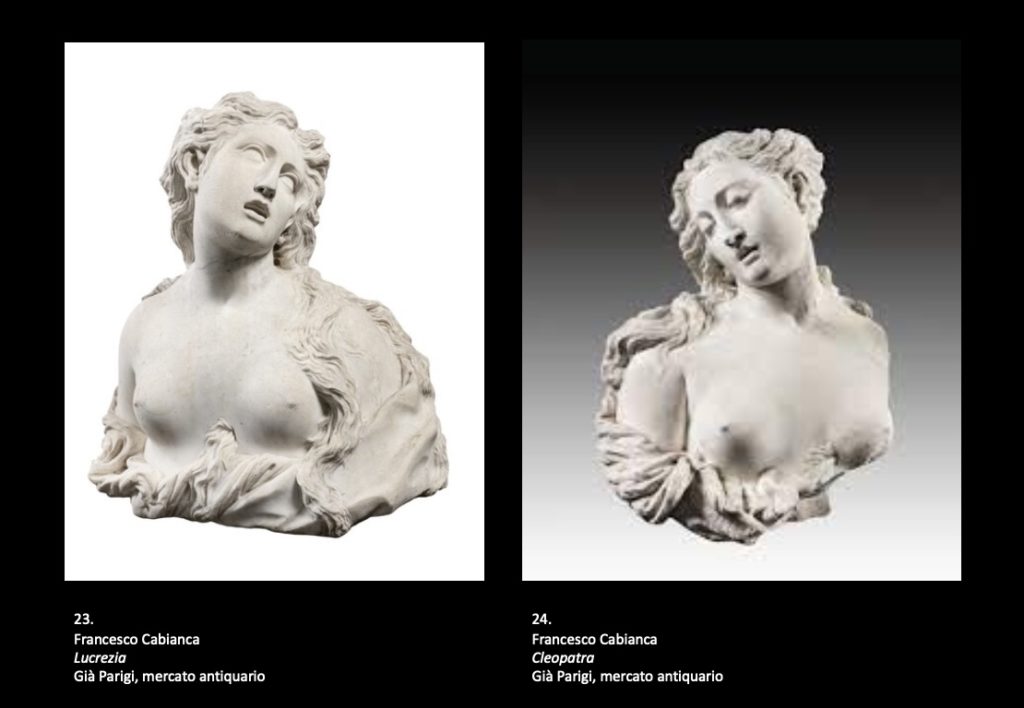

Among the most notable examples of this kind of work created by Cabianca and intended for collectors we can mention the beautiful female bust in the Museum of Fine Arts in Budapest[12] (fig. 22) and the pair of busts, depicting two heroines of antiquity, Cleopatra and Lucretia (figs. 23-24), which recently appeared on the Parisian antiques market[13].

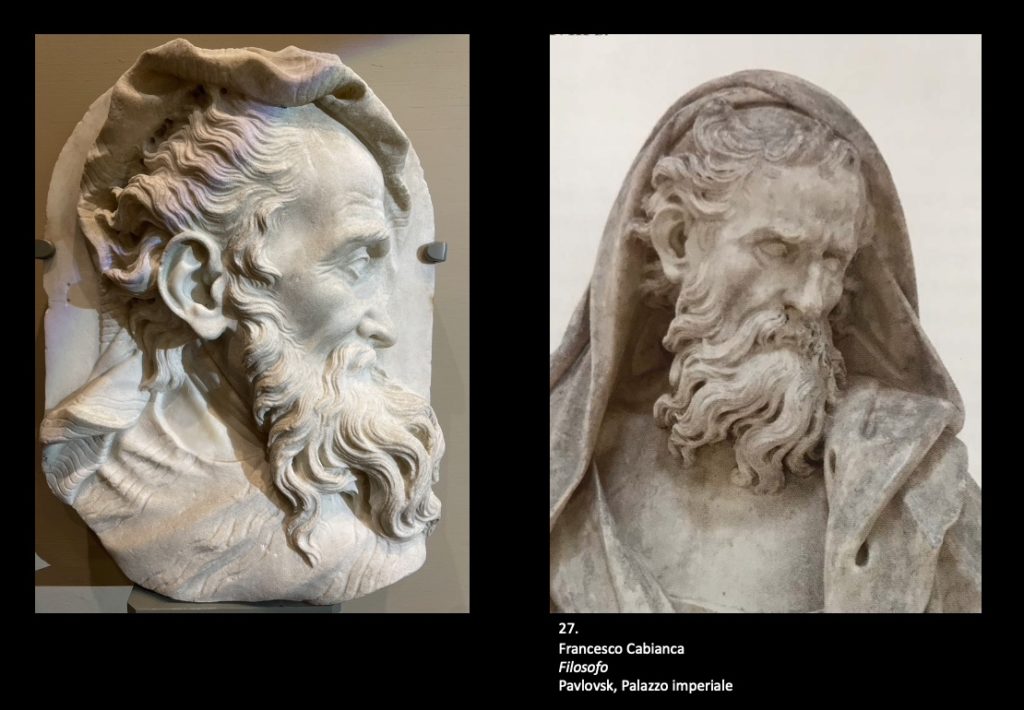

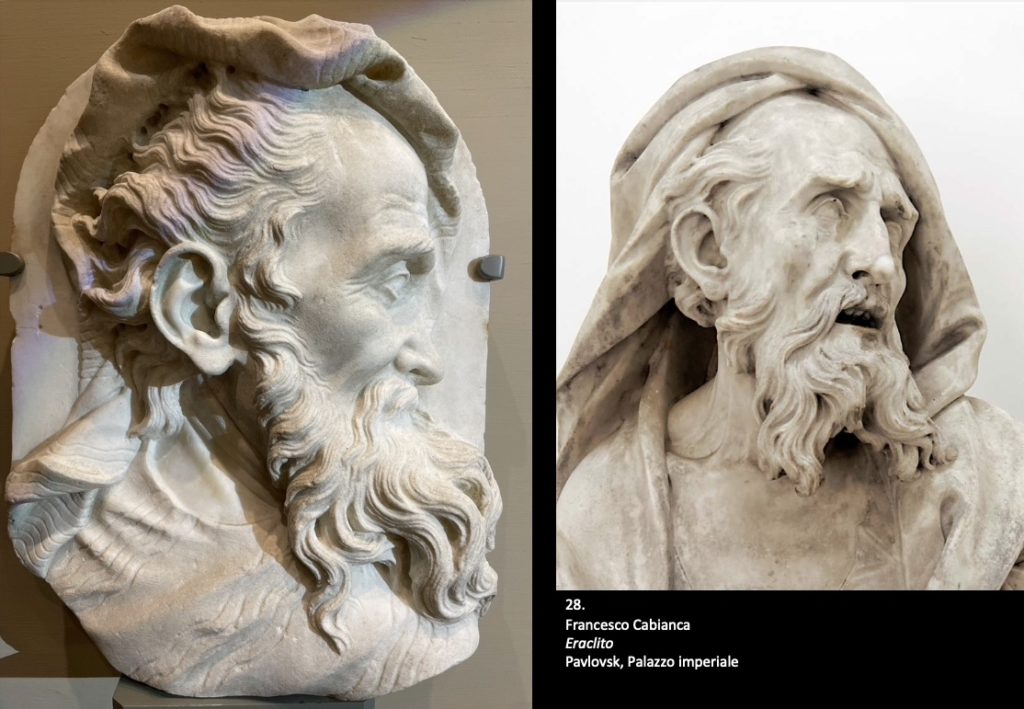

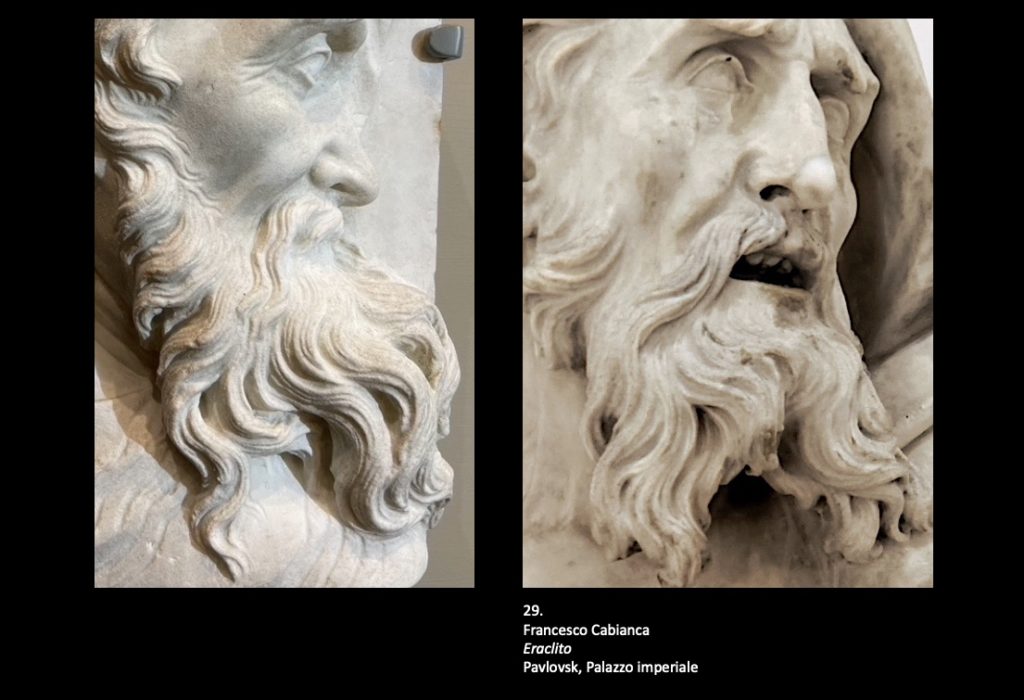

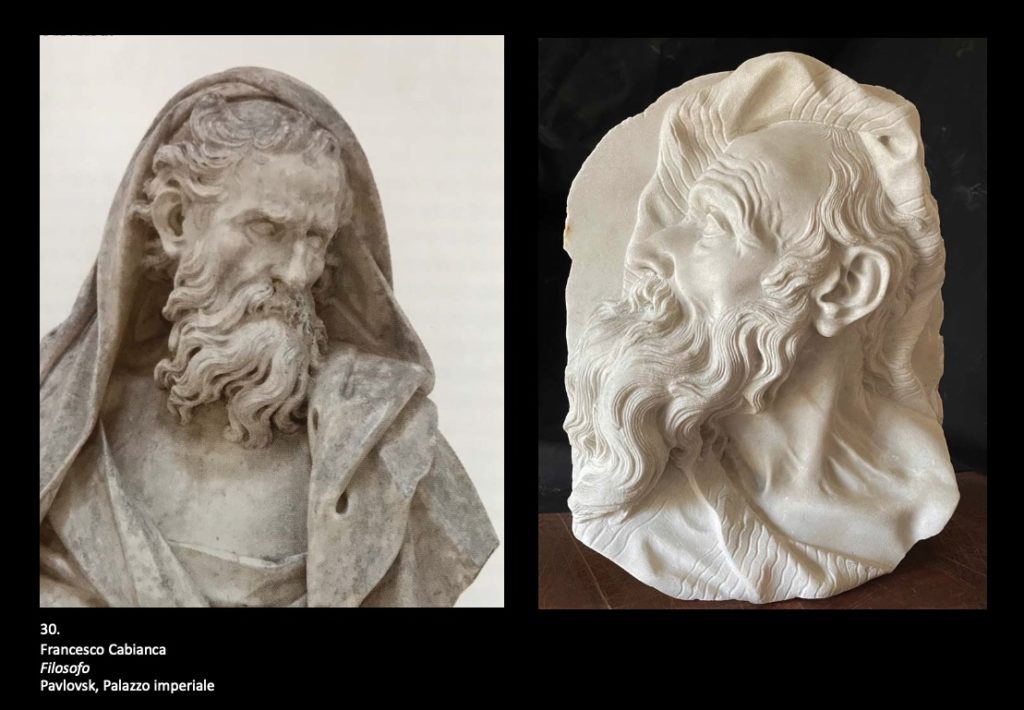

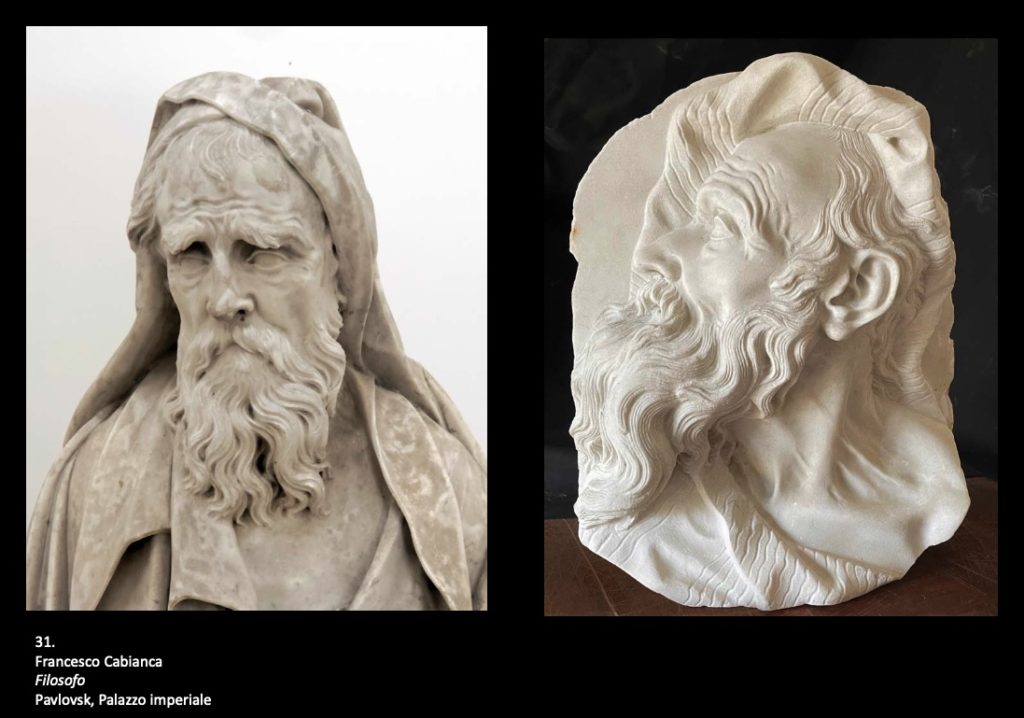

But for Cabianca, as for other sculptors of his time, it was precisely the imaginary portraits of ancient philosophers that must have represented one of the subjects most sought after by collectors. Of his production related to this theme at least four other busts of philosophers preserved in the Imperial Palace of Pavlovsk near St. Petersburg are known[14], in addition to the bust in Palazzo Corner. And it is both of these that naturally constitute the main and most persuasive terms of comparison for ascribing to Francesco Cabianca the two profiles examined here.

In fact, by juxtaposing all these ‘portraits’ of the elderly with each other, we can observe that they exhibit the same typological and stylistic characteristics (figs. 25-31). The physiognomic features are similar, equal is the shape of the eyes and nose, the flesh of the cheeks under the cheekbones is hollowed out in the same way to render well the idea of the elderly thinker’s gaunt face.

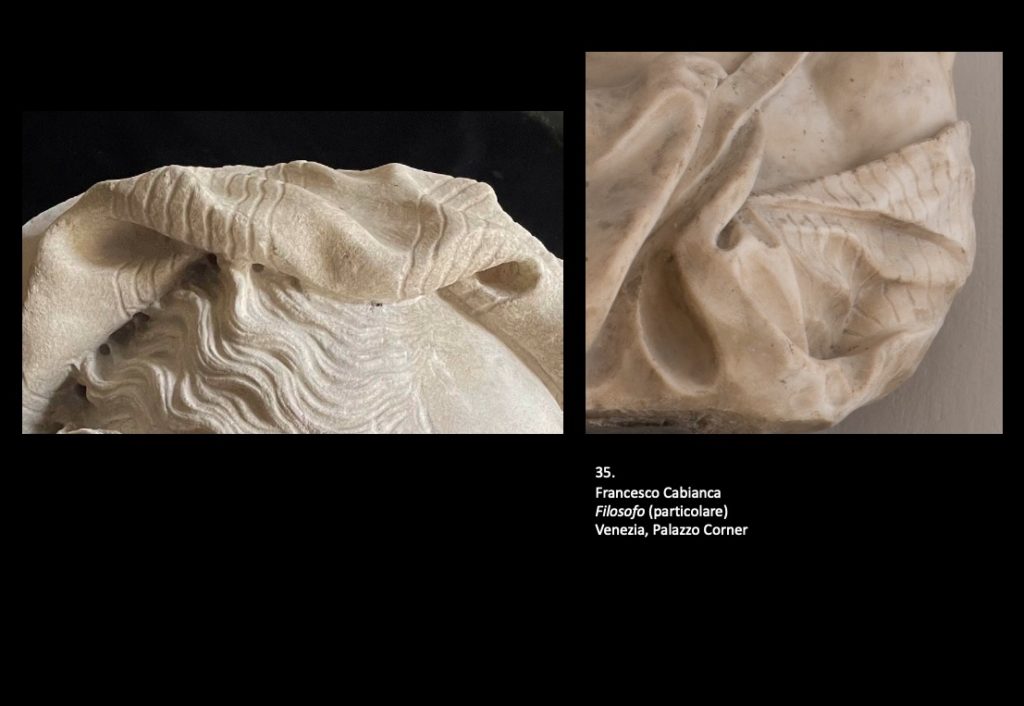

The hair and beards appear in the same way disheveled and shot through with a sudden quiver; the long, wavy locks are deeply sculpted and finished on the surface for their full extent with the tip of the chisel notching continuous lines. In this way, the sculptor gives the works similar effects of lively chiaroscuro and dramatic, theatrical sense.

Looking closely, in detail, at the faces of these elderly figures (fig. 32) we can even better see the correspondences in the design of anatomical details and execution technique. Similar is the shape of the orbital cavity and the small, sunken eyes; also identical is the design of the eyelids and the brow arch casting a shadow on the upper eyelid. Also similar are the wrinkle furrows carved into the forehead and root of the nose (figs. 32-33).

Finally, similar is the workmanship of the mantle that covers the figures, arranged according to thick, irregular folds that form deep hollows, and whose surface, thanks to the use of the toothed chisel, emulates striped fabric in some cases (figs. 34-35).

Thanks to these comparisons it is therefore possible to attribute with certainty to Francesco Cabianca our profiles depicting a pair of philosophers.

In excellent state of preservation, these two reliefs were in the possession of Murray Acton-Adams (1886-1971) who was a flamboyant interior decorator and antiques dealer between the wars in London and acted on behalf of William Randolph Hearst and the Burrell’s: they constitute, in conclusion, a fine example of the typically Venetian genre of small collectible sculptures that was practiced in the Serenissima Republic in the 17th and 18th centuries by all the leading artists.

Simone Guerriero

February 2024

Please contact LASSCO if you would like to view this Report in Italian, in Large Print or Hard Copy formats.

Reference bibliography

V. Coronelli, Viaggi del P. Coronelli. Parte prima, Venezia 1697, p. 24

V. Coronelli Guida de’ forestieri sacro-profana per osservare il più ragguardevole nella Città di Venezia, Venezia 1700, p. 16

D. Martinelli, Il Ritratto overo le cose più notabili di Venezia, Venezia 1705, pp. 676–677

T. Temanza, Zibaldon [1738], edited by N. Ivanoff, Venezia-Roma 1963, pp. 42-46

C. Semenzato, La scultura veneta del Seicento e del Settecento, Venezia 1966

O. Ferrari, L’iconografia dei filosofi antichi nella pittura del sec. XVII in Italia, “Storia dell’Arte”, 57, 1986

P. Goi Il Seicento e il Settecento, in La scultura nel Friuli Venezia Giulia, II, Dal Quattrocento al Novecento, Pordenone 1988, pp. 133-227

S. Guerriero, I rilievi marmorei della cappella del Rosario ai Ss. Giovanni e Paolo, in “Saggi e memorie di storia dell’arte”, 19, 1994

M. De Vincenti, Sui monumenti Manin del duomo di Udine, “Venezia Arti”, 11, 1997, pp. 61-68

S. Androsov, Pietro il Grande. Collezionista d’arte veneta, Venezia 1999, pp. 218-222

Da Sansovino a Canova, photographic repertory edited by A. Bacchi, Milan 2000, pp. 711-713 (with previous bibliography)

M. De Grassi, Francesco Cabianca e la prima attività veneziana di Pietro Baratta, in Francesco Robba and the Venetian Sculpture of the Eighteenth Century, proceedings of the International Conference of Studies (Ljublijana, October 16-18, 1998), edited by J. Hofler, Ljubljana 2000, pp. 51-60

Orazio Marinali e la scultura veneta tra Sei e Settecento, exhibition catalogue (Vicenza, Palazzo Thiene, 6 December 2002 – 12 January 2003) edited by M. De Vincenti, S. Guerriero, F. Rigon, Cittadella 2002, pp. 12-15

S. Guerriero, Le alterne fortune dei marmi: busti, teste di carattere e altre “scolture moderne” nelle collezioni veneziane tra Sei e Settecento, in La scultura veneta del Seicento e del Settecento: nuovi studi, edited by G. Pavanello, Venezia 2002

S. Guerriero, Il collezionismo di sculture ‘moderne’, in Il collezionismo d’arte a Venezia. Il Seicento, edited by L. Borean and S. Mason, Venezia 2007, pp. 43-62

S. Guerriero, Per un repertorio della scultura veneta del Sei e Settecento. I, “Saggi e memorie di storia dell’arte”, 33, 2009, pp. 236-237.

D. Tulic, Per Francesco Cabianca in Praesidium Venetorum – Templum Apparitionis Beatae Mariae Virginis a Pellestrina, “Arte Documento”, 25, 2009, pp. 191-195

M. Klemenčič, Nekaj novosti o delu beneškega baročnega kiparja Jacopa Contierija (in notica o Francescu Cabianci), “Acta historiae artis Slovenica,” 15, 2010, pp. 39-50

D. Tulić and M. Pintarić, Antonio Michelazzi i Francesco Cabianca: A nova djela u Italiji i Hrvatskoj, “Ars Adriatica,” 10, 2020, pp. 141-164

Tableaux Dessins Sculptures 1300-1900, Sotheby’s Paris, 30 June 2020, lots 62-63

M. Clemente, Francesco Cabianca: addende al catalogo (in press)

Notes to Part II

[1] S. Guerriero, Le alterne fortune dei marmi: busti, teste di carattere e altre “scolture moderne” nelle collezioni veneziane tra Sei e Settecento, in La scultura veneta del Seicento e del Settecento: nuovi studi, edited by G. Pavanello, Venezia 2002.

[2] For a biographical profile of the sculptor see S. Zanuso, in Da Sansovino a Canova, photographic repertory edited by A. Bacchi, Milan 2000, pp. 711-713 (with previous bibliography). See also M. De Grassi, Francesco Cabianca e la prima attività veneziana di Pietro Baratta, in Francesco Robba and the Venetian Sculpture of the Eighteenth Century, Proceedings of the International Study Conference (Ljublijana, 16-18 October 1998), edited by J. Hofler, Ljubljana 2000, pp. 51-60; D. Tulić, Per Francesco Cabianca in Praesidium Venetorum – Templum Apparitionis Beata Mariae Virginis a Pellestrina, “Arte Documento”, 25, 2009, pp. 191-195; M. Klemenčič, Nekaj novosti o delu beneškega baročnega kiparja Jacopa Contierija (in notica o Francescu Cabianci), “Acta historiae artis Slovenica”, 15, 2010, pp. 39-50; D. Tulić and M. Pintarić, Antonio Michelazzi i Francesco Cabianca: A nova djela u Italiji i Hrvatskoj, “Ars Adriatica”, 10, 2020, pp. 141-164.

[3] T. Temanza, Zibaldon [1738], edited by N. Ivanoff, Venice-Rome 1963, pp. 42-46. On the statue of Antinous, see most recently E. Noè, L’antico, Versailles, Venezia: il caso dell’Antinoo di ca’ Corner, “Ateneo Veneto”, 7/11, 2008, pp. 141-156.

[4] T. Temanza, Zibaldon [1738], edited by N. Ivanoff, Venezia-Roma 1963, pp. 42-46. S. Guerriero, Il collezionismo di sculture ‘moderne’, in Il collezionismo d’arte a Venezia. Il Seicento, edited by L. Borean and S. Mason, Venezia 2007, p. 62.

[5] M. De Grassi, Francesco Cabianca e la prima attività veneziana di Pietro Baratta, in Francesco Robba and the Venetian Sculpture of the Eighteenth Century, proceedings of the International Conference of Studies (Ljublijana, October 16-18, 1998), edited by J. Hofler, Ljubljana 2000, pp. 51-60.

[6] D. Martinelli, Il Ritratto overo le cose più notabili di Venezia, Venezia 1705, pp. 676–677.

[7] V. Coronelli, Viaggi del P. Coronelli. Parte prima, Venezia 1697, p. 24: “Tra gli scultori fanno figura Giovanni Bonazza, e Francesco Casa Bianca”; see also V. Coronelli, Guida de’ forestieri sacro-profana per osservare il più ragguardevole nella Città di Venezia, Venezia 1700, p. 16.

[8] C. Semenzato, La scultura venta del Seicento e del Settecento, Venezia 1966, p. 41.

[9] See M. De Vincenti, Sui monumenti Manin del duomo di Udine, “Venezia Arti”, 11, 1997, pp. 61-68.

[10] S. Androsov, Pietro il Grande. Collezionista d’arte veneta, Venezia 1999, pp. 218-222.

[11] T. Temanza, Zibaldon [1738], edited by N. Ivanoff, Venezia-Roma 1963, p. 42.

[12] See https://www.mfab.hu/artworks/136149/.

[13] See Tableaux Dessins Sculptures 1300-1900, Sotheby’s Paris, 30 June 2020, lots 62-63. The two busts were recognised as works by Francesco Cabianca by Maichol Clemente.

[14] S. Guerriero, Le alterne fortune dei marmi: busti, teste di carattere e altre “scolture moderne” nelle collezioni veneziane tra Sei e Settecento, in La scultura veneta del Seicento e del Settecento: nuovi studi, a cura di G. Pavanello, Venezia 2002.