The Temple of Friendship Coade Stone Urns

The fifteenth hole at the Harleyford Golf Club is testing. It’s 378yards from Tee to Green that, for the brave right-hander, requires a full-blooded drive with a “draw” on it; the ideal shot should clear the trees and peel to the left, dropping down on to the dog-leg fairway. Get it right and the second shot into the green on the Par 4 hole should be a doddle. Those back on the championship tee will line-up their drive with a handsome octagonal stone temple on the left of the fairway – perhaps picking one of the eight urns topping its parapet as a marker to aim for.

The Temple is a striking building and club members, caught in a shower, will doubtless occasionally shelter in it. It’s in a ruined condition but has, in recent years, been tidied up. In the past it had long been engulfed by trees and scrub – but this has been chopped away revealing it at last. It is known as “The Temple of Friendship”. The urns on the top are rather impressive too but they are not original, they are replacement copies. Four of the eight originals that were made by Eleanor Coade in her famous London workshops, exactly 250 years ago, have come to light. They have been acquired by LASSCO. We have restored them. And they are now for sale. They are very special urns indeed.

The Friends Behind the Temple of Friendship

On paper, William Clayton (1718-83) was never likely to have inherited much at all as he was the tenth child, the fifth son, of his father Sir William Clayton (d.1744), 1st Baronet of Marden in Surrey. However, he and his older brother Kenrick (1713-69), the eighth born, were the only boys to have survived infancy, together with Anne and two other sisters. On their father’s death in 1744, Kenrick duly inherited the title, and the land including Marden Park in Surrey, and became Sir Kenrick Clayton, 2nd Baronet of Marden. Considerable swathes of Surrey and Sussex came with this inheritance – Kenrick and William’s father had once bragged that he could ride from Eastbourne to London without losing sight of his estates.

Aged 21, William took over his late father’s seat in parliament; he and Kenrick now held the two seats for Bletchingley, Surrey – a “Rotten Borough” – whose tiny vote they controlled. And William inherited Harleyford House, on the Thames near Marlow, Buckinghamshire, which his father had bought in 1736 extending the original Clayton estates in the Hambleden valley down to the Thames. The house was in a bit of a state though due to a couple of fires. And no, there wasn’t a golf course then[i]. And nor was there a Temple – not yet. We’re coming to that.

As a teenager William had been schooled, after his time at the Middle Temple, by a private tutor called John Thomas (1712-93) – a gifted young man from Carlisle who had arrived at The Queen’s College, Oxford, in 1730, before moving on to a post as an assistant master at a Theological Academy in Soho Square, London. Clearly the tutor was soon held in high esteem by William’s father because, after Thomas was ordained in 1737 (somewhat hurriedly it seems), he had him installed as Rector at Bletchingley, the parish church for the Clayton country seat at Marden Park. It was a lucrative post that came with influence over the few voters ensuring those parliamentary seats were guaranteed. Furthermore, he sanctioned that John Thomas should marry his recently widowed daughter Anne[ii] (Kenrick and William’s elder sister). They were wed in 1738.

There was only six years in age between John Thomas and his former pupil William Clayton, and now brothers-in-law, the two men remained great friends.

With such influential sponsors as the Claytons, and now married into the family, John Thomas’ career prospered. In 1749 he was appointed “Chaplain in Ordinary” to King George II (r.1727-60), a post he retained under George III (r.1760-1820) who was later, in 1780, to visit Harleyford House with the Royal Family.

In Buckinghamshire, William Clayton took things in hand at Harleyford. The old house, that occupied a beautiful spot on a curve of the Thames, was demolished. In 1755 he engaged the services of architect Robert Taylor (1714-88) to build him a mansion. This house is a wonderful Georgian villa and it still stands today as built. It was Taylor’s first country house and was noted for its compact form with a shift in emphasis towards a more free-flowing informal interior on the raised piano nobile. It has glorious river views[iii].

The Rev. Dr John Thomas meanwhile continued on an impressive upward trajectory in the Church and in London Society. He became Dean of Westminster in 1768. And at this time he was awarded the Order of the Bath. A full-length portrait of him by Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723-92) was commissioned. It depicted the new Dean in his Order of the Bath finery in front of the Abbey. Reynold’s diaries show that, quite beyond the dates at which John Thomas sat for the revered portraitist, he was known to pop round for dinner on occasion too.

John Thomas and Anne did not produce any children, but from her first marriage, Anne (Lady Blackwell), did have a son and a daughter. William Clayton meanwhile married three times and produced three children, including another William, (who later, by a twist of fate was to inherit his grandfather’s baronetcy from his cousin).

Four decades went by and John Thomas, who had so prospered by his long association with the Clayton family, announced that he would build a permanent reminder of their friendship – to mark it in perpetuity: he would build a “Temple of Friendship” at Harleyford. It is known that he paid for it and that he gifted it to William Clayton but not much more is recorded. This is the building that today finds itself alongside the fifteenth fairway at the Harleyford Golf Club.

The first recorded reference to the Temple was in 1797. T. Langley[iv], in his perambulations around the county was entranced by it and, crucially, jotted down the inscription above the door (the inscription itself is now lost). Then, only twenty years since its completion, and still presumably standing in clear parkland without trees, he enthuses about the park in general and the temple in particular:

“The situation of Harleyford is extremely beautiful, commanding a fine reach of the river, and screened from the north by a rich drove, where the beech and fir blend their contrasted colours. The lawn of the sweetest verdure, and ornamented with venerable chestnuts and other forest trees, forms the appropriate scenery of this admired residence. The walks are extensive, and open to many varied and interesting views. Of these the terrace attracts particular notice. The few seats, grotto, and buildings being well situated, and not crowded, have their full effect; but the temple of Friendship claims attention, not more from the beauty of its architecture, or its lovely situation, than from its being a tribute of respect and regard from the late Dr. Thomas, bishop of Rochester, to this family. Over the door is this short inscription:

Amic. XXXX ann.

Grat. plur.

F.F.

J.T. Ep. Rof. 1775”

The abbreviated Latin (expanded to: “Amici XXXX Annos, Gratias Pluribus, Fratres, John Thomas, Epifcopus Rochefter 1775”) translates as:

Friends for 40 years ,

With Much Gratitude,

Your Brother in Law,

John Thomas, Bishop of Rochester 1775[v]

But the friendship between Thomas and Clayton wasn’t the only reason that John Thomas commissioned the building in 1772. After a marriage of 34 years his wife Anne, William’s sister, had passed away that year. The building wasn’t just a Temple of Friendship – it was a memorial.

The Temple of Friendship – a Temple and Mausoleum

There is no documentary evidence to support the claim that Launcelot “Capability” Brown (1715-83) landscaped the river valley around Harleyford House – many estates make that claim, probably far too many – but with Robert Taylor working on the house, it has long been thought that William Clayton brought Capability Brown in to remodel the Thames-side park – it has his hallmarks. With Capability Brown’s involvement or not, incorporating a classical stone temple into an engineered picturesque landscape would have been considered usual, if not essential, in those days. The list of fashionable country estates that were remodelling their parks with lakes, islands, bridges, strategic arboreal plantings, and temples during the 1760’s and 1770’s is a long one. Capability Brown was a busy man.

Both the siting of the “Temple of Friendship”, on high ground away from the house, aligned with the main drive to Marlow, and its form: an octagonal temple, classically austere, clad with ashlar masonry, cut with niches and ringed with full-height columns all make it appear as a mausoleum. It even has a crypt.

The carved stone columns are interesting. When Nikolaus Pevsner swung past in his Morris Minor in 1960 he seems not to have had the time to lay eyes on the temple – lost as it was in the woods. He does mention something intriguing though[vi]:

“It is said that there was here [on the main house] originally a portico, and that the columns were removed for use around the rotunda in the grounds known as the Temple of Vesta. This temple is now in decay.”

One wonders how much credence we can give to the salvaged columns story as there doesn’t seem to be a candidate elevation on the house that a porch could have been removed from. The “Temple of Vesta” that he mentions, one assumes, must be the “Temple of Friendship” named in error.

Whilst the temple has all the salient features of a mausoleum – with the exception of an actual tomb (Anne was buried at Bletchingley) – tentatively, we can still place it within the exclusive and refined world of parkland Mausolea.

The practice of building Mausolea in English country estates, and the form they took, had only been recently established over the preceding decades. It was John Vanbrugh (1664-1726) who had introduced the idea of parkland mausolea at Castle Howard, only forty years before. As Roger White puts it in “Georgian Arcadia: Architecture for the Park and Garden”[vii],

“Until the construction of the Castle Howard Mausoleum in its parkland setting in 1731-42, there was no such thing in England as a physically free-standing mausoleum outside consecrated ground.”

He ventures that,

“…the English Gentleman may have been subconsciously rendered susceptible to the idea by having done the Grand Tour, seeing for himself the ruins of ancient Mausolea in the Roman Campagna and bringing home the mausolea stocked paintings of Claude Lorraine … [et al]”.

Vanbrugh, when working for the East India Company in the 1680’s, had visited the Mausolea-resplendent cemetery at Surat in India and had drawn the tombs, re-imagining them, classicising them, and stripping them of their Mughal ornament. Many of his drawings show free-standing domed tombs, octagonal or cylindrical in format. Years later in Yorkshire he remembered these drawings and sketched a domed, cylindrical temple for Lord Carlisle, ringed without by a tight peristyle of columns.

Vanbrugh didn’t live to see the Castle Howard Mausoleum built, nor did his assistant Nicholas Hawksmoor (1661-1736) who designed the building but died during the construction of it. In the subsequent sale of Hawksmoor’s estate it is notable that 68 drawings of envisaged mausolea were listed. Later, Sir William Chambers (1722-96) in the 1750’s, was found to have a thing for drawing them too. White suggests that,

“a unique characteristic of the mausoleum in particular was that as its occupants were inevitably dead, their requirements were very straightforward, and therefore the architect had the kind of freedom to design “ideal” structures that appealed especially to classicists and still more to neo-classicists”[viii].

Vanbrugh didn’t persuade his other great patron the Duke of Marlborough to commission a mausoleum at Blenheim Palace, the Duke had already expressed his intentions to be interred at the church; in this way religion and family tradition probably largely explains why there are only a few parkland mausolea built in the next 25years[ix], and fewer still that were ever occupied with a coffin.

The most spectacular of these was Robert Adam’s (1728-92) handsome four-square domed mausoleum at Bowood in Wiltshire for the first Earl of Shelburne who died in 1761 and was laid to rest in it.

By the middle of the century, the placing of funerary buildings in a picturesque landscape was an admirable conceit. There are even examples of landscapes being ornamented with fictitious graveyards – tombs memorialising no-one in particular. Only the extremely wealthy could afford a mausoleum to preserve their remains and it was a signifier of The Enlightenment too – it portrayed a direct relationship to God without church interference. And for some, it portrayed something more radical still – absence of a relationship with God at all.

In “Architecture and the Afterlife” Howard Colvin confirms there were no tombs in 17th Century English park landscapes but explains that with Capability Brown and the informal picturesque landscape of the 18th Century, came three types: firstly, a “Roman” tomb – to evoke a Claude or Poussin painting, secondly, “an ornamental building that was also a memorial or tribute to a real person who was buried elsewhere; and the third was the tomb or mausoleum that was the actual place of burial of an individual or family”[x]. The Temple of Friendship is of the second variety (Adam’s Bowood mausoleum is of the rare third variety).

With these prototypes in mind, a significant influence on the design of “The Temple of Friendship” can perhaps be attributed to one architect and he was well-versed in mausolea. He was a much-travelled Suffolk gentleman called Nicholas Revett (1720-1804) and for many years he was working very locally for the notorious Sir Francis Dashwood (1708-81).

Nicholas Revett, Sir Francis Dashwood and polygonal towers

In 1751, in London, Nicholas Revett and James “Athenian” Stuart (1713-88) had announced their intention to the Society of Dilettantes, that they were heading back to Athens, in order to survey and draw the great ancient buildings of the Acropolis and Agora. This won them numerous subscribers. Intrigued, Dashwood (a founder of the Society) had then engaged Revett to apply both his knowledge of, and enthusiasm for, ancient Greek architecture to his home: West Wycombe House. The resultant West Portico (as opposed to the Palladian east portico that preceded it) is credited as the first Greek Revivalist structure in Europe.

Revett was to become further involved with the remodelling of the West Wycombe park and the temples therein. One was the Temple of Music positioned on an island in the lake. Another was an octagonal tower called “The Temple of the Winds” loosely based on “The Tower of the Winds” that Revett had drawn in Athens.

In 1762, Revett and Stuart finally managed to publish “The Antiquities of Athens”[xi]. It had been a fraught mission to accurately measure and draw the ancient buildings of the Acropolis and Agora – thwarted as they were by the turbulence they were confronted with in the streets, by plague, and by the refusal of the Turks, who had a garrison atop the Acropolis, to grant them access to many of the ancient sites they were hankering to record.

After the publication of “The Antiquities of Athens”, with a £500 endowment from his late friend George Bubb Dodington (1691-1762) in hand, Dashwood commissioned Revett to build him a Mausoleum. It was a monster. It occupied a dominant spot high on West Wycombe hill and could be seen for miles. It still can.

Revett’s design was Hexagonal in plan, cut with archways and niches and finished in flint. It was built by John Bastard. The flint had been un-earthed during Dashwood’s project to put the impoverished local population to work mining chalk from the hill on which his Mauseleum was to stand[xii]. The mining formed a network of tunnels, caves and chambers deep within the hill.

Dashwood is remembered for his notorious “Hellfire Club” – a branch of the dilettantes holding debauched and ritualised parties in those caves. Rumours of heavy drinking, prostitution, pornography and even satanism abounded. Less well remembered is that the regular soirees were originally held at Medmenham Abbey a few miles away on an idyllic spot on the Thames that could be discretely accessed by boat from London. Dashwood had clubbed together with some of his fellow “Monks of Medmenham” and in 1751 had acquired the Abbey on a long lease. The core of this group included Paul Whitehead (1710-7) a satirist and poet, secretary and steward of the club (like Dashwood, later to opt, partially, for a mausoleum interment on his death[xiii]). The Abbey was mostly a ruin when they acquired it; Dashwood put Nicholas Revett to work remodelling it. Medmenham Abbey, it should be pointed out, is right next door to Harleyford House.

We can only conclude that William Clayton and Sir Francis Dashwood were in regular contact (if not attending the same parties). By extension John Thomas must have been familiar with Nicholas Revett, an architect working both next door to Harleyford at the Abbey and on the huge hexagonal mausoleum at West Wycombe. All this was going on in the 1760’s and can only have been influential on John Thomas’ choice for the design of “The Temple of Friendship”.

Strangely, Dashwood’s mausoleum doesn’t have an ancient model. It isn’t drawn directly from Revett’s Athenian explorations. But the octagonal “Temple of the Winds” down in the main park certainly is, and as we will see, another rendition of it was about to be built in Oxford.

What is also very telling, and what links the Dashwood mausoleum and The Temple of Friendship, is that on completion, the flint walls of Dashwood’s, polygonal mausoleum on West Wycombe Hill, were topped with Coade Stone urns – ordered from Eleanor Coade’s Manufactory in Lambeth.

The Harleyford Coadestone Urns

In 1772[xiv], we can imagine the grieving John Thomas, aged 60, nipping out from work at Westminster Abbey and arriving, probably by boat, just a short trip downriver from the then new (stone) Westminster Bridge, for an appointment at Eleanor Coade’s workshops at The King’s Stairs – a wharf on the Surrey bank. He will have had with him drawings of his intended Temple. Once there, he may well have been ushered-in to meet with Eleanor Coade (1733-1821) (her mother, the elderly Mrs Coade (d.1796), had probably retired by this point).

John Bacon (1740-99) himself, may have been there too. Bacon was Coade’s brilliant signing: an extraordinary sculptor, he was the talent that was to have a hand in most of Coade’s patterns for the next twenty years. John Thomas, by then Bishop of Winchester, was there to consider designs for urn embellishments to go on the top of his planned mausoleum-like building in order they could be drawn-in to the plans he was carrying. They may well have discussed the urns that had recently been supplied to Sir Francis Dashwood to crown his new mausoleum on the hill at West Wycombe. The Rev. Dr John Thomas, soon-to-be Bishop of Rochester wanted similar.

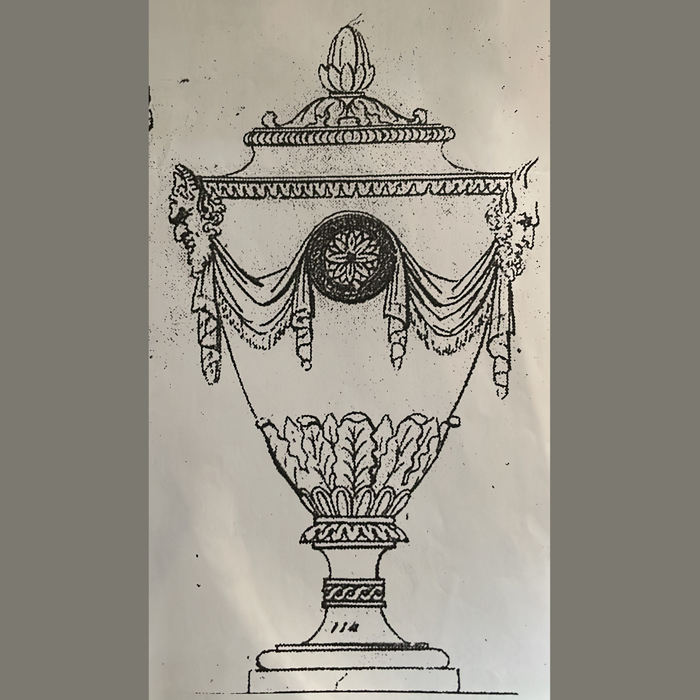

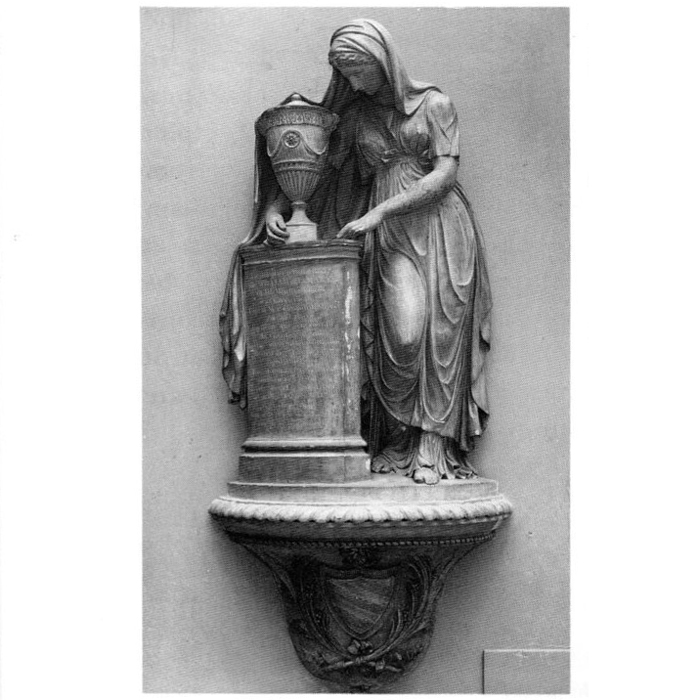

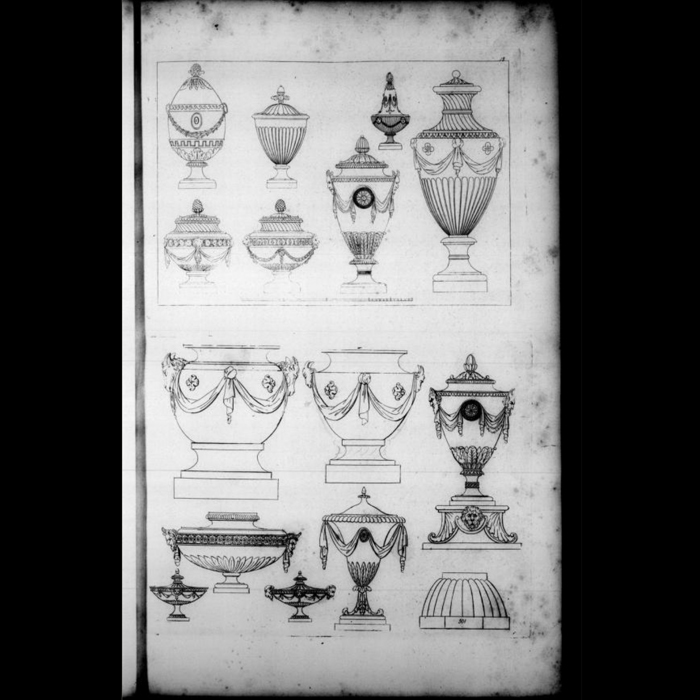

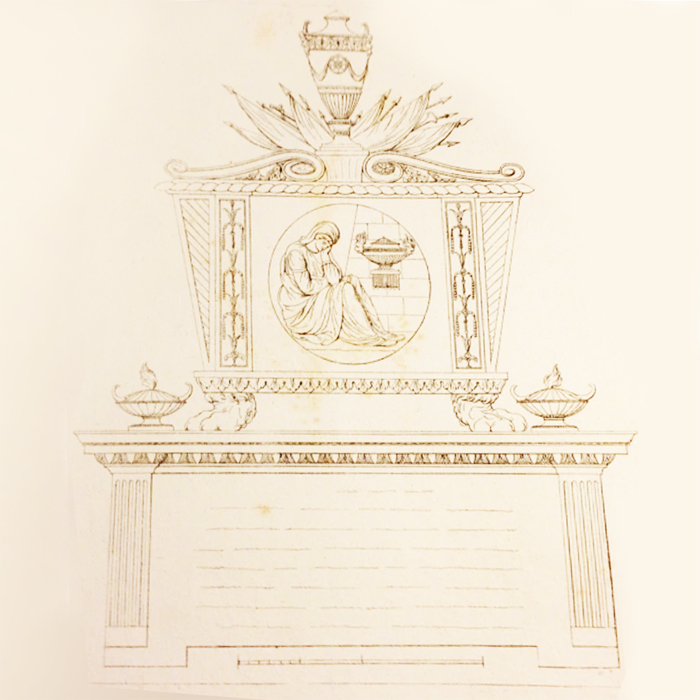

In her comprehensive book and gazetteer of “Mrs Coade’s Stone”[xv], Alison Kelly was unaware of the Temple at Harleyford (in 1990, when she was writing, the Temple was still lost in the woods). But she lists a number of funerary monuments that John Bacon was working on in the 1770’s. They were to become stock patterns at the manufactory and featured in the 1777 catalogue of etchings from which orders could be made.

One of the monuments, the “Vestel”, has a classically draped woman leaning over a Greek Urn – it is the pattern of the Harleyford urn. Both the figure and the urn were designed by John Bacon; numerous examples can be found where he adapted and combined his existing sculptural elements in this way to create sculptural groups. He was adept at it and for Coade it was clearly lucrative.

Kelly describes the Vestal monument as “best selling” and traces a number of places where examples of it can still be seen today (happily, being funerary monuments they all bear dates). The earliest she could find, dating to 1788, is a Vestal monument at Langley Marish, Buckinghamshire (about 10miles from Harleyford). The same model, also appears at Fenstanton Church in Huntingdonshire, a memorial to none-other than Frances Brown, the widow of Launcelot “Capability“ Brown[xvi]. And of four further examples cited, one, dating to 1800, can be seen in the Victoria and Albert Museum today[xvii].

In the 1777 catalogue, the urn appeared in other sculptural groups as well as on its own with various iterations: different lids and feet. This all demonstrates both the longevity of the designs once the moulds had been made, and, that the Harleyford urn, the urn in-the-round unaccompanied, is almost certainly the first time this pattern is used – it precedes all the others. As such it is one of the earliest known examples of Coade stone and with it the funerary connection is established atop a mauseleum.

At the time, John Thomas wasn’t just building in Buckinghamshire. Assured the Bishopric of Rochester (he was invested in 1775) he had the crumbling “Palace of Bromley” in Kent demolished and rebuilt. The re-building work, in brick, was undertaken from 1774-6 exactly as the Temple of Friendship was being built in Buckinghamshire. The triangular pediment over the principal façade at Bromley bears a carved armorial – it is John Thomas’ Coat of Arms. The Coat of Arms looks like it is made of stone. Research continues to find out if it is known who carved it. Or perhaps cast it in Coade stone. Perhaps, on the occasion of the visit that we are imagining, Thomas discussed the Palace of Bromley job with Coade and Bacon too.

***

“The Temple of Friendship” has the appearance of a mausoleum and Bacon’s urns had a funerary connection too, but such buildings, whilst being Momento Mori were also seen as picturesque “eye-catchers” in the landscape. We don’t know for certain who designed it. The “Historic England” listing suggests it is “…possibly by Sir Robert Taylor” but this sounds tentative and is presumably ventured only by dint of the fact that it was Taylor that had built the main house thirty years before. There is another contemporaneous building that we might perhaps compare the temple to.

If John Bacon wasn’t at his workplace at the Coade Manufactory on the day we imagine John Thomas dropping in, he may well have been in Oxford. There are numerous examples of Coade stone to be found on Oxford’s fine Georgian buildings but in 1772 Bacon was spending a lot of time in Oxford for another reason – he was working on some carved reliefs.

The Radcliffe Observatory

James Wyatt (1746-1813), had taken over the building of the Radcliffe Observatory in Oxford from Henry Keene, and redesigned it, even after the foundation stone had been laid. Originating from Burton-on-Trent and working in his father’s practice there, Wyatt had gone on to receive acclaim for his “Pantheon”[xviii] on Oxford Street in London. It was probably the Pantheon success that won him the Observatory job. The year was 1772. The tower was up and in use within a year – if not completely finished (work continued on it until 1794).

For inspiration, Wyatt had been looking at Nicholas Revett and James “Athenian” Stuart’s “The Antiquities of Athens”. The top levels of the observatory tower Wyatt built were based on the 1762 drawings by Revett of the “Tower of the Winds’ in Athens. The original tower is octagonal in plan – Wyatt adopted it to more of a square with canted corners, in order to better incorporate doorcases. The frieze around the top of the Athens tower, dating from about 50 BCE, features fantastic winged relief figures personifying the “Eight Winds” and these were duly adapted after Revett’s drawings and carved in stone. It was John Bacon of the Coade Manufactory who carved them (the bronze sculpture of Atlas and Hercules supporting the globe crowning the top of the tower is his work too).

Wyatt was a great fan of the Coade product and was prolific in both incorporating Coade castings in his work (Kelly[xix] identifies 29 commissions through his career). He was an early adopter too – he had ordered plaques and pilaster capitals for the Pantheon as early as 1770 and Wyatt is known to have himself designed architectural details for reproduction in the Coade workshop such as the ionic capitals he had just installed at Heaton Park near Manchester.

Wyatt raised his Radcliffe Observatory tower on a much larger lower register – demi-lune in plan with blind niches similar to those on the Temple of Friendship. He ornamented it with two series of relief plaques. First were the twelve Signs of the Zodiac – on eleven oval and round reliefs (Scorpio and Libra were combined). The second series were rectangular plaques – figural personifications of “Morning”, “Noon” and “Night”. All the plaques were made in Coade stone.

In Conclusion

In all this polygonal tower and mauselea building in the Thames Valley in 1772 it would seem very likely that John Thomas would have commissioned an architect for “The Temple of Friendship” from amongst the circle here described (rather than the ageing Robert Taylor). The Temple of Friendship was built just after Revett’s Coadestone topped Mauseleum ten miles away on Wycombe Hill, and was built at the same time as Wyatt’s octagonal Observatory at Oxford – only thirty miles away and based on Revett’s drawings. John Thomas and his brother-in-law William Clayton must have known Dashwood and Revett in the neighbouring estate to Harleyford and would also have been familiar with the “Antiquities of Athens” of 1762. And they all knew John Bacon and Eleanor Coade in the early days of the Coade workshop.

The chalk that Francis Dashwood mined from the hill at West Wycombe was for rebuilding the road that came from High Wycombe – it’s a three mile run of the London to Oxford road that he rebuilt. It lines up directly with his Mausoleum. The Coade stone casts variously destined for Harleyford and for Oxford would have been packed in barges in Lambeth and floated in horse-drawn river barges up the Thames, but John Bacon, John Thomas, James Wyatt and Nicholas Revett et al would have made the trip from London to Oxford on the improved then road. Passing Dashwood’s mausoleum and heading for Oxford they would have followed the road up hill to Stokenchurch atop the Chilterns and made the perilous descent to Lewkner before heading for Wheatley Bridge to cross the River Thame. They would have passed an Inn on the right called The Three Pigeons. Any of them, on any of their numerous trips, may have even stopped for refreshments. The Three Pigeons today, 250years later, is where the Temple of Friendship Coade Stone urns can now be found.

Epilogue

On his death in 1780 Sir Francis Dashwood, Lord le Despenser was interred high on the hill at West Wycombe in his Mausoleum – alongside his wife to whom he was notoriously unfaithful. He had partied his way around Scandinavia, Germany and Italy, often in fancy dress, and was founder, and key player, in many of the London Society’s elite clubs. A staunch Tory Member of Parliament he was vehemently opposed to Walpole and his Whig governments and was to serve, briefly (and ineptly) with Lord Bute as Chancellor of the Exchequer – a serious role that seemed somewhat to quench his partying at Medmenham. The portrait bust that marks his resting place in the Mausoleum was carved by John Bacon.

Sir Robert Taylor architect of Harleyford House, went on to become one of the leading and most influential architects of the period. He succeeded Sir William Chambers as The King’s Surveyor of Works, was responsible for the rebuilding of the Bank of England (as completed by Sir John Soane) and he taught John Nash and Samuel Pepys Cockerell among others. It was Taylor who re-designed London Bridge – sweeping away the buildings thereon – and completed numerous notable architectural commissions in London and the shires. He used Coade stone ornament in at least two of them. He may be the architect of “The Temple of Friendship” at Harleyford but he probably isn’t the front-runner.

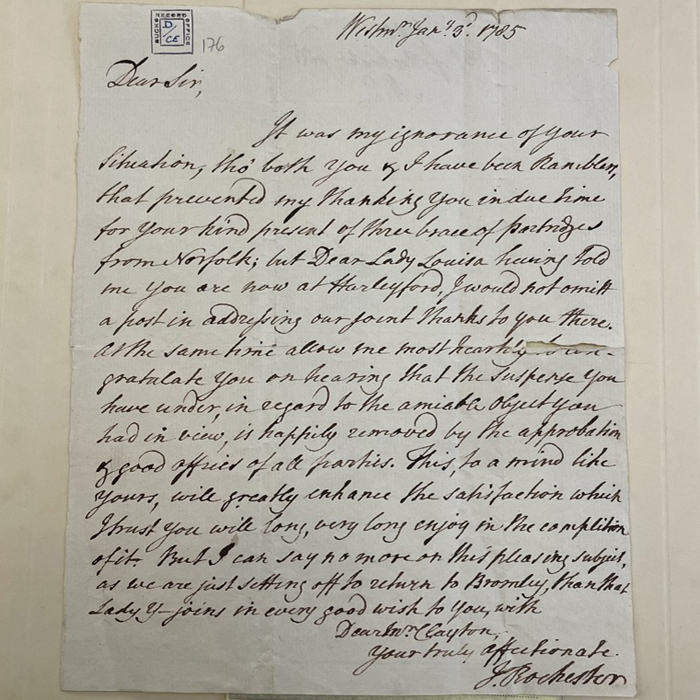

William Clayton, the tenth born, passed the beautiful Harleyford House that he had had built by Taylor to his son William. And the Baronetcy did ultimately come to the Claytons of Harleyford. Clayton always stayed close to his brother-in-law John Thomas, his former tutor, who had built a Temple both to commemorate their friendship and to memorialise the death of Anne who connected them by marriage. The affection between the two men, and the younger William can be seen in surviving letters held at The Buckinghamshire Records office at Aylesbury.

Harleyford House stayed in the Clayton family for another two hundred years and eventually inspired Kenneth Grahame to imagine it as Toad’s riverside mansion in “Wind in the Willows”: Toad Hall.

Nicholas Revett and James “Athenian” Stuart had a falling-out after the publication of the 1762 first edition of “The Antiquities of Athens”. Revett felt that Stuart took all the glory – exacerbated by Stuart’s adoption of the “Athenian” epithet. Revett sold his rights in the publication to Stuart who, with subsequent editions and resultant architectural commissions, did rather well. Stuart himself built two “Temple of the Winds”, the first in 1765 at Shugborough in Staffordshire, the second at Mount Stewart in Northern Ireland[xx]. Stuart lived just north of Leicester Square and succumbed to alcoholism – he was well known in taverns thereabouts.

Revett never cashed-in in the same way and, with his patron Dashwood gone, he fell on hard times. Despite his wide influence, only a few of his designs were ever built other than the work he did for Dashwood.

The portrait by Sir Joshua Reynolds depicting John Thomas in his Order of the Bath finery has, after 250 years, briefly re-emerged on show. From July 2023 until April 2024 (only) it has been hung on public display in Rochester Cathedral in commemoration of the tri-centenary of Reynolds’ birthday. The actual robes Thomas wears in the painting have been un-earthed by the Cathedral and are on display too.

Just down the nave in Rochester Cathedral is found a spectacular tomb. The Henniker Monument of 1797 features a sarcophagus flanked by two figures: “Truth” is a female statue holding a torch, “Time” is a fabulous winged elderly figure. The latter has a fantastic physique and a long beard. He holds a scythe and an hour glass. It is one of the finest Coade funerary monuments known. Father Time is attributed, tentatively, to the sculptor Thomas Bankes (perhaps only due to a contemporaneous, and possibly erroneous attribution, in The Gentleman’s Magazine). However, comparison to John Bacon’s figural work, including his “Druid” at Shugborough and his ”Father Thames” at Ham House, do seem to point to the hand of Bacon (Bankes is not otherwise known to have worked for Coade) – but this could be a contentious point. One could look to what influence John Thomas the Bishop of Rochester might have had at the Cathedral in the commissioning of this Coade memorial sculpture given the links to his old friend John Bacon at Coade. Furthermore Bacon’s son, another John, is responsible for the proximate fine marble carved marble tomb commemorating Henniker’s husband whom she had pre-deceased.

Mrs Eleanor Coade died aged 81 at her Camberwell Grove home in 1821. A devout Baptist, she never married and was buried in a family grave at Bunhill Fields in London – a grave now lost, destroyed in the Blitz. In an extraordinary career spanning fifty years she developed a huge range of her Lythodipyra sculptural products that can be found decorating some of the most celebrated buildings and gardens of Georgian Britain and beyond. John Bacon worked for Coade until his death in 1799. He is seen as a founding figure of The British School of Sculpture.

Rev. Dr John Thomas, Bishop of Rochester, soon married again – to Dame Elizabeth Yates in 1775, the year the Temple of Friendship was completed at Harleyford. They moved into the new Palace of Bromley he had just built. He lived a long life and died in 1793, aged 81. He was laid to rest alongside his first wife Anne at Bletchingley Church in Surrey, on the Clayton estate, where they had lived for much of their long marriage. John Thomas is memorialised in Westminster Cathedral with a marble portrait bust. It too was carved by the John Bacon in 1794.

Four of the Coade Stone Urns from the Temple of Friendship have been acquired by LASSCO Three Pigeons and are now available for sale. They were found in a garden near to Harleyford House where they had served as ornaments for a number of decades having been removed, in a collapsed state, from the temple. They were used as models to make composition stone replacements when the temple was restored in the twentieth century. The temple itself was Listed Grade II in 1987 and has subsequently been restored.

Ask at the golf club and no one knows anything about the Temple at all, the members are too intent on that tricky shot – bending the ball onto the 15th fairway to ensure the next shot onto the green is a doddle.

Anthony Reeve

LASSCO Three Pigeons

Further Reading

For Harleyford House See:

Marcus Binney “The Villas of Sir Robert Taylor”, Country Life July 1967

John Cornforth, “Early Georgian Interiors”, Yale University, 2004, pp72-73

Country Life, “Harleyford”, June 2010

Mark Girouard, “Life in the English Country House”, Yale University Press, 1978, pp.199-201

John Harris, “The Artist and the Country House”, Sotheby’s , 1979, p 281

Thomas Langley M.A. “The History and Antiquities of the Hundred of Desborough, and Deanery of Wycombe in Buckinghamshire; including the borough towns of Wycombe and Marlow and sixteen parishes” R. Faulder & B&J White, London, 1797

Hazel Malpass, “Harleyford” Published on line by Local History Group of the Marlow Society.

N Pevsner “The Buildings of England: Buckinghamshire”, Penguin Books, (1960), p157

N Pevsner & E Williamson, “The Buildings of England: Buckinghamshire”, Yale University Press, (1994), pp 372-373

Dorothy Stroud, “Capability Brown”, Country Life (1975), p 228

Also:

Country Life, 27 (4 June 1910), pp 810-19; 142 (27 June 1967), pp 17-18

The Gardener’s Magazine, (30 January 1904), pp 87-90

The English Heritage Register of Parks and Gardens of Special Historic Interest (Swindon)

For Mausolea and their place in country estate settings – See:

Howard Colvin, “Architecture and the After-Life”, Yale University Press, New Haven & London, 1991

Roger White “Georgian Arcadia: Architecture for the Park and Garden”, Yale University Press, London, 2023,

For Coade Stone See:

John Davies, “Garden Ornament”, Antiques Collectors Club, 1991, Illustration of Coade Urns, etching c.1778 p345, Summary of Coade Stone pp161-175

Alison Kelly, “Mrs Coade’s Stone”, Self Publishing Association. in assoc. with The Georgian Group, 1990,

Hans Van Lemmen “Coade Stone”, Shire Publications, 2006

[i] Although 1736 does happen to be the year that the first ever golf course was created – in St. Andrew’s Scotland.

[ii] Anne Clayton b. 1709 was Kenrick and William’s eldest sister who had married Sir Charles Blackwell (1700-41), very young, (before 1721) producing two children. Blackwell died in 1736. Anne, Lady Blackwell, then married John Thomas.

[iii] See: John Cornforth, “Early Georgian Interiors”, Yale University, 2004, pp72-73

[iv] See: Thomas Langley M.A. “The History and Antiquities of the Hundred of Desborough, and Deanery of Wycombe in Buckinghamshire; including the borough towns of Wycombe and Marlow and sixteen parishes”, R. Faulder & B&J White, London, 1797

[v] This translation is offered guardedly – any corrections are welcomed. The translation of abbreviated Latin inscriptions is a language of its own – the “F.F” could be right but could be more revealing still.

[vi] N Pevsner “The Buildings of England: Buckinghamshire”, Penguin Books, (1960), p157

[vii] In Roger White “Georgian Arcadia: Architecture for the Park and Garden”, Yale University Press, London, 2023, pp253-268

[viii] White, Op Cit.

[ix] There is an Anti-clerical bent to the concept- as overtly expressed by Vanbrugh and more generally by Grand Tourists who were fascinated by the Roman tombs on the Appian Way and the burial practices being revealed in Egypt as the century progressed.

[x] Howard Colvin, “Architecture and the After-Life”, Yale University Press, New Haven & London, 1991, p329

[xi] Nicholas Revett and James Stuart, “The Antiquities of Athens”, Society of Dilletantes, 1762

[xii] The chalk was to embank and improve the straight road leading from High Wycombe – lining up directly with Dashwood’s mausoleum and church that he rebuilt on the hill. The road today is the A40 and the effect can still be admired.

[xiii] Whitehead was buried at St. Mary’s Teddington but minus his heart which was placed in an urn at Dashwood’s mausoleum. His heart would on occasion be retrieved from the urn to show visitors until 1829 when it was stolen.

[xiv] We’ll stick with 1772 for this imaginary meeting but as indicated, it is early in the life of the Coade works. There is nothing to suggest that the idea of planting Coade urn embellishments onto an otherwise austere temple didn’t come later, as per the plaques at the Radcliffe Observatory in Oxford whose ornamentation work ran until 1794 by which time J.C.F. Rossi was old enough to have made them – it is he to whom the plaques are credited. However, the Greek entablature of off-set columns (as demonstrated in later examples, particularly in the designs of Sir John Soane at both Pitzhanger and Lincoln’s Inn with off-set columns, and as per the drawings of Revett and Robert Wood, does seem to require urn finials. So – we must assume the finials were drawn-in at the outset. Crucially, that they appeared in the Coade catalogues of 1777 – they were being produced by the time of those catalogues and were likely installed at Harleyford by then.

[xv]

[xvi] Kelly, Op Cit p *** Launcelot Brown is known to have installed Coade sculptures in his landscaping projects on a number of occasions including Croome Court.

[xvii] Kelly, Op. Cit p*** The church of St. James at Hampstead was demolished – the tomb gifted to the V&A

[xviii] To see the enthusiastic response to the opening of The Pantheon See: B. Weinreb & C. Hibbert “The London Encyclopedia”, Macmillan, 1983, pp597-8

[xix] Kelly, Op. Cit

[xx] There’s good pictures and summary of Stuart’s “Temple of the Winds” found at the blog site “The Irish Aesthete”