No products in the basket.

22nd March 2023

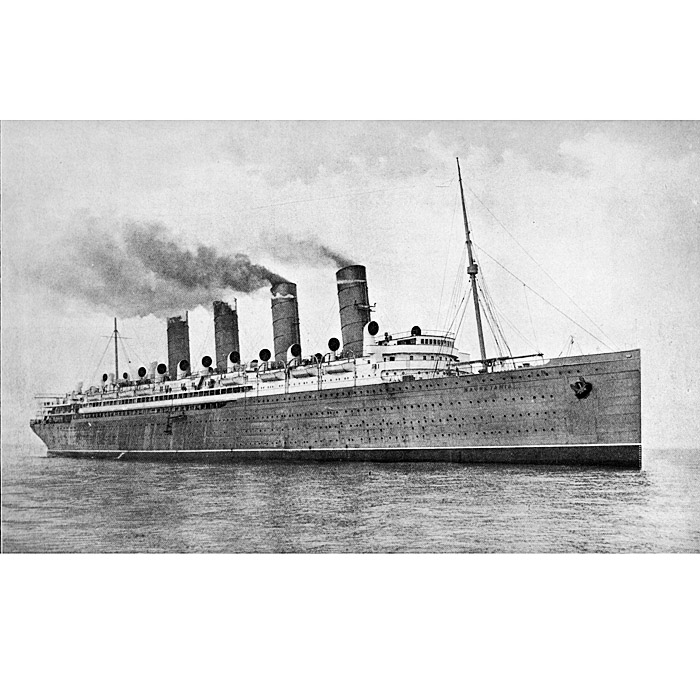

Panelling salvaged from R.M.S Mauretania

In our ceaseless trawling of the barns, attics, stables and out-houses of fusty institutions and country houses we get the opportunity to find and purchase the most extraordinary things. The year started with the discovery of a large stack of wooden panelling, thick with dust and leaning up in an old garage in the grounds of a country estate in Wiltshire. This panelling, it transpires, formed part of the sumptuous panelled interiors made in 1905 for what, in her day, was the largest, fastest and best-loved passenger liner of the early 20th Century: RMS Mauretania. It is an extraordinary opportunity to acquire some of the panelling from the ship – available to view and buy at LASSCO Three Pigeons.

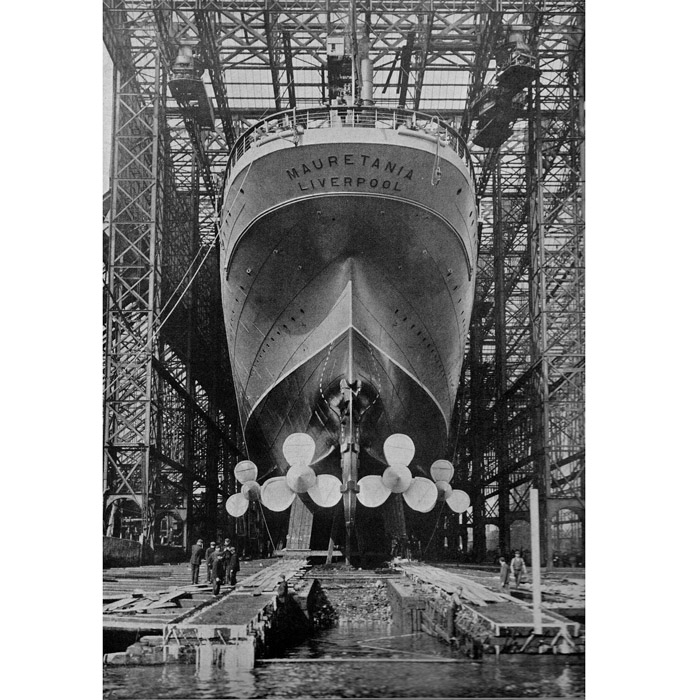

The Mauretania was at the heart of the great age of passenger liners. She, and her sister ship RMS Lusitania, were built by the Cunard line, with direct backing from the British government, to answer the competition from German merchant fleets and American investors who were trying to dominate the increasingly lucrative trans-Atlantic routes.

Of the vast ocean-going liners of Edwardian times it’s the unfortunate ones that are remembered first: RMS Titanic (White Star Line) succumbed to an iceberg collision on her maiden voyage in 1912 and RMS Lusitania went down, holed by a single torpedo from a German submarine, U-Boat 20, in 1915 – both sinkings with awful levels of fatalities; the shock of those sinkings still resonates today. All of the “Greyhounds of the Seas” though, plying the cross-Atlantic routes as America boomed, were revered at the time – none moreso than the Mauretania. They were emblematic of progress, triumphant engineering, modernity, national pride, empire and globalisation.

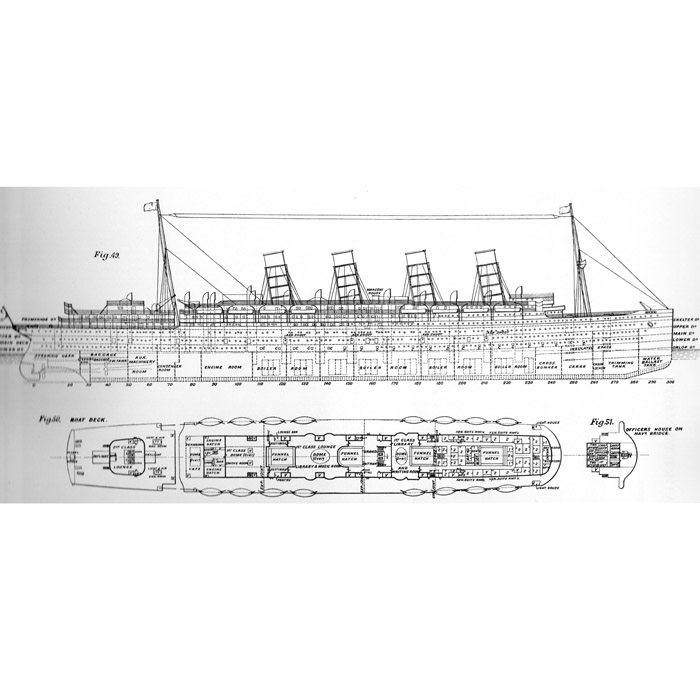

When launched into the Tyne in 1906 RMS Mauretania was the biggest moving man-made object ever built – a mere 3feet longer than her sister-ship the Lusitania who had slipped into the Clyde a few months earlier. Cunard had taken a big gamble too – in this age of innovation they opted, during the build itself, to adopt new steam-turbine engines to generate the power needed to get this vast liner propelled across the Atlantic. For prestige and for business they were striving, above all, to win back the “Blue Riband” from the Germans – the coveted prize held by the passenger ship with the fastest average speed for the crossing. First Lusitania and then Mauritania vied and successfully bagged the honour but from 1907 to 1929 the Mauretania alone held the prize: un-surpassed in speed. The gamble had paid off.

She burned coal to power the turbines – vast amounts of it: with 194 furnaces on board it took 6500tons to get her to New York at the required minimum 24.5knots. (That is not just one train load comprising 30 railway trucks full of coal, it’s 21 such trains, for just one crossing). Cunard had their own coal mine producing 9500tons of top-quality “Best Welsh” steam coal per day in order to meet these needs.

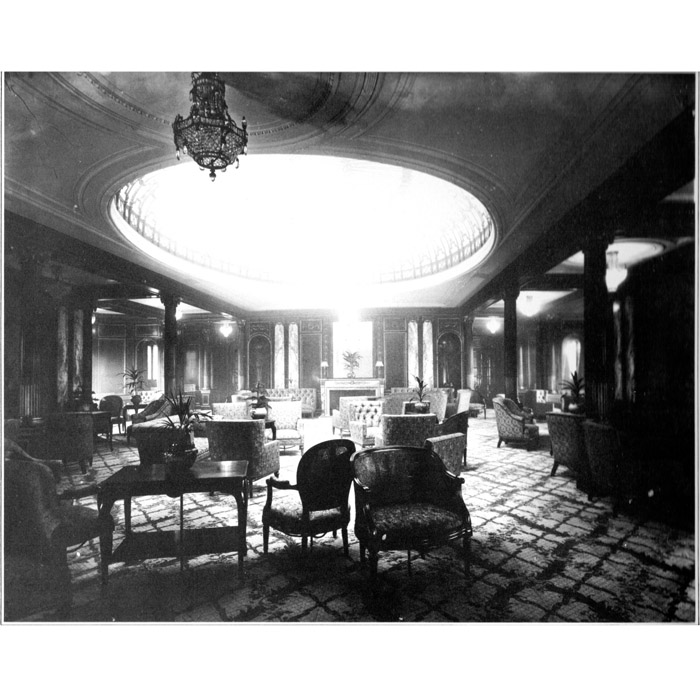

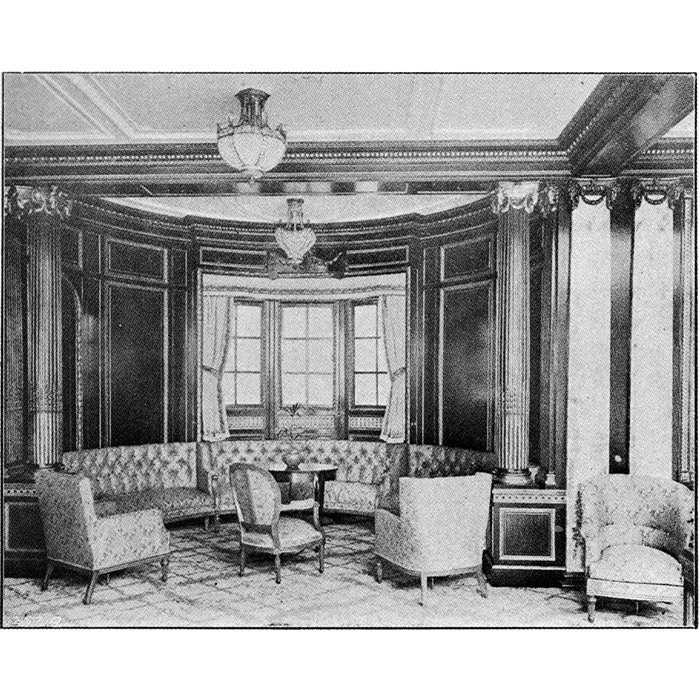

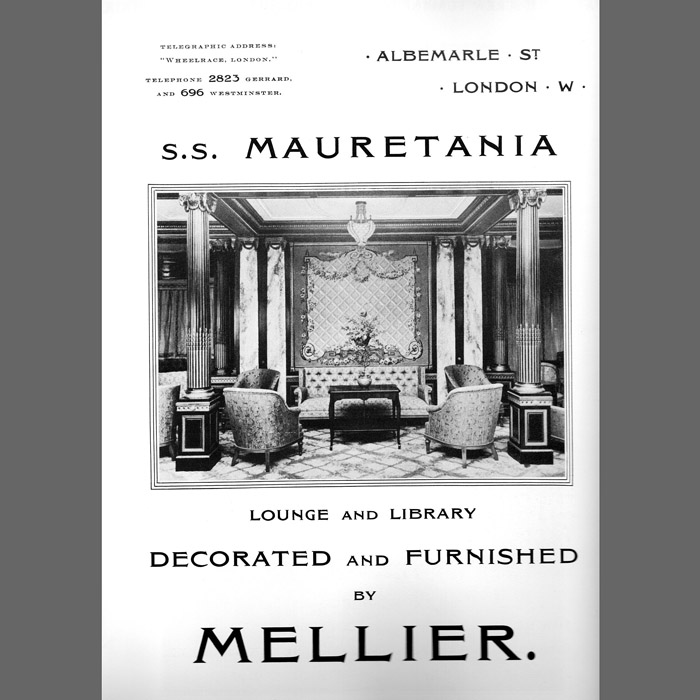

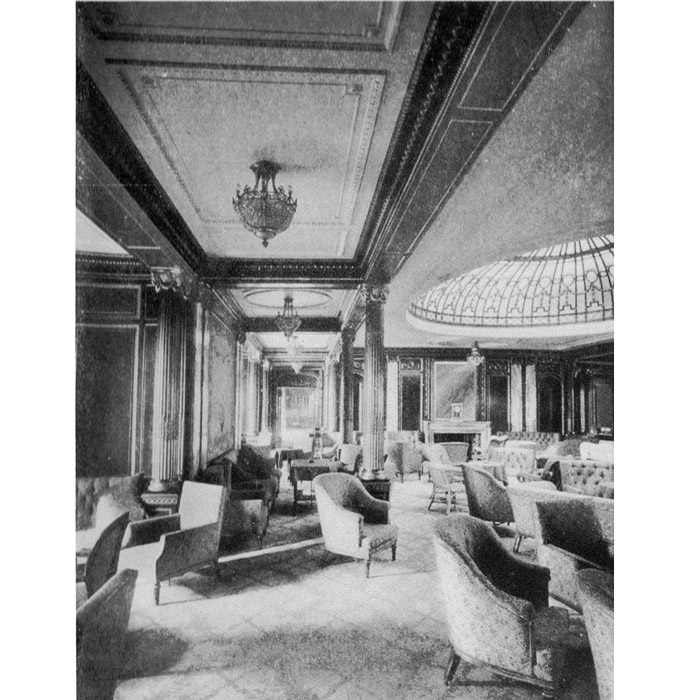

With these ships Cunard had got the Atlantic crossing down to five days. But to win the business, in a competitive luxury market, the trip had to made In Style. For the fit-out of Mauretania, Cunard went to Harold Peto (1854-1933) a well-travelled architect and sought-after garden designer, to provide the ship with show-stopping interiors. He charged eye-watering sums but it was not an investment that the owners came to regret. The First Class Lounge, the Smoking Room, the Library and Writing Room and the double-height Dining Rooms were all palatial and lavishly decorated. Top-lit from domed glass skylights the principal rooms were lined with the finest wooden panelling that money could buy. Exotic quartered veneers, fluted columns and giltwood pilasters were complimented with acres of Wilton carpet and matching upholstery, tapestries and curtains. Fleur-de-Peche marble columns, carved fireplaces and gilded mirrors completed the look. Peto went to two London firms for the woodwork: “W. Turner Lord & Co” and “Mellier & Co.” both distinguished cabinet-making firms. (The designs for the second and third class decks were approved by Peto but supplied and fitted by the shipyard – woodwork for these was by Robsons & Sons of Newcastle).

The ”Engineering” Journal published a dedicated edition in order to detail the amazing addition to the Cunard fleet in 1907. It described The Lounge and was effusive in its praise:

“…Never has the interior of a ship had more careful thought bestowed upon it, nor has such an earnest desire after purity of style been manifested. … The original designs for all of the first class saloons were prepared by the well-known architect, Mr H. A. Peto, the styles which he first suggested having been adhered to throughout, and he is to be congratulated upon the admirable results attained”.

“The Lounge and Library have been decorated by Messrs. Ch. Mellier & Co., Albemarle Street London, and upon entering them one is transported in a moment from the cold realities of a modern steamship to the exquisite taste of a French salon of the eighteenth century. Thick carpets, comfortable chairs, soft colourings and bright, but carefully shaded, electric lights, all combine to give an atmosphere of luxury and beauty hitherto considered impossible even in modern steamships”.

There is no room here to tell of the extraordinary career of this famous ship – her scores of Atlantic crossings, her life as a troop-ship and hospital ship in the Great War (she was “dazzle” painted in 1918), and the record-breaking speeds, collisions, refits, breakdowns and dramas that a life on the high seas entailed. The travelling public loved the ship dearly – even those bunked in the lower decks who had to endure horrendous vibrations as the turbines roared beneath them. Entertainment included fine dining, music and dancing; for cruises there were sometimes a canvas swimming pool on deck, cinema screenings, boxing matches and deck games. High Society loved to see, and be seen in, the prestigious rooms. Unusual friendships were founded, thrown together by circumstance on those opulent decks. On one crossing in February 1931 Charlie Chaplin fell-in with Captain Malcolm Campbell, a fellow passenger and then holder of the land speed record – Chaplin, suffering from seasickness, joked with Campbell that “I have the idea that the way sailors overcome illness is to tighten their belts. I am now wearing mine under my armpits”.

In her later years the Mauretania was a vanguard of the Cruise Ship industry. In 1920 Cunard were quick to see the potential in prohibition America: by cramming the ship with millionaires and taking them on a spin of the Mediterranean. £10,000 of booze was despatched on the first such trip and it was an annual event thereafter. In the 1930’s the Mauretania was pulled from Atlantic services and made the Caribbean cruise a regular jaunt; she was re-painted in “cruising white” (a necessary cooling measure for a non-air conditioned steel ship in the tropics).

The Great Depression was a test for the shipping operators and business dropped away. Cunard and The White Star Line had now merged, and the ship, now an elderly representative, was mothballed from September 1934 – to be soon joined by the younger RMS Olympic. But it was still a surprise to many in March 1935 when it was decided that she was to be sold for scrap to Metal Industries Ltd of Rosyth. The announcement,

“… sparked a wave of public sentiment.. . Since 1907, the Mauretania had become part of the British Empire, soldering on in both war and peace, a constant symbol of reliability and steadfastness in changing times. Even after she had been eclipsed by much larger and more luxurious liners, even after she had lost the Blue Riband, her last claim to fame, she continued to hold a special place in the hearts of Britons and Americans alike.”

Even F.D. Roosevelt – who notoriously hated all travelling – wrote in protest at the loss of his favourite liner.

Hamptons of London were engaged to sell off the fixtures and fittings from the ship at Southampton before she would embark on her final trip to Rosyth to be broken. Southern Railways put on special trains from Waterloo to the docks for the viewings. Two rounds of auctions were held – eight days of selling over two weeks in May. Bidding was slow on Day 1 but “when the First Class Smoking Room and Dining Saloon went up [on Day 2], bidding picked up steam. From there interest seemed to escalate; bidders with connections to the ship came in to try and snatch a memento of her”.

The walnut panelled smoking room was acquired by Kensington New Church to provide a fabulous backdrop to the chancel of their newly built church in Notting Hill. The church has recently changed hands but the panelling – not mentioned in the Estate Agent’s particulars – is still there today. St. John the Baptist Church in Padiham Lancashire has got more in its 1937 extension.

The fabulous Library and Writing Room was snapped up in its entirety – together with a number of the more prestigious cabin fixings – by a certain J. Arthur Rank and his associate Charles Boot. The pair rebuilt the panelling as a grand restaurant in their new project at Heatherden Hall in Iver Heath Buckinghamshire. Their film studio there became known as “Pinewood” and the Rank Organisation became a huge brand name in film distribution. The Restaurant later became the Board Room and is available for use as a film location today – the origin of the richly panelled room is not mentioned on the Pinewood website.

Much of the 1st Class Lounge panelling was bought by Ronald Avery – a wine merchant from Bristol. Back in Park Street he had it installed to form “The Mauretania” Bar and Grill. This premises was more recently occupied by the “Java” nightclub; their disco ball hung from the framework of one of the ship’s glazed dome skylights. The club is now closed and the building partly unoccupied. Excess to Avery’s requirements was a curved bay from the 1st Class Lounge and another run of flat panels – these were ultimately stored at Avery’s friend’s country estate in Wiltshire where LASSCO found them under eighty-eight years of dust.

The auction catalogue described the Mellier & Co panelling from the 1st Class Lounge as:

“quartered and mitred in acanthus framings, intercepted by uprights of pearled leaf medallions and paterae, friezes and mouldings of Vitruvian scrolls, echinus … all of carved gilt wood”.

We are gently sponging away eighty eight years of dust and the colour and quality of the carving and the veneers is emerging. it is remarkable what this panelling has witnessed and endured. It survived 269 double crossings of the Atlantic in a ship notorious for her vibration when going full speed. Conscripted soldiers embarking for the Gallipoli campaign would have leant against these panels as the great liner, then a troop ship, was enlisted to take them there. Later, when a Hospital Ship in the Channel, others were lined up in hospital beds nursing injuries sustained at the Western Front and would also have admired the woodwork. First Canadian, then American troops would have marvelled at the opulent interiors as “The Maury”, on another mission for the Admiralty, rushed them to Europe to join the fight. Through the Roaring Twenties the panelling would have resounded to the sound of The Charleston. The panelling survived changes in fashion – the temptation to refit with Art Deco interiors was never realised – and it even survived some fairly serious on-board fires and floods. For 25years and over a million miles it formed the sounding boards for travellers enjoying a level of luxury and speed never seen before. Now it is available for sale at LASSCO Three Pigeons in land-locked Oxfordshire *Click Here* for details – who knows where it will end up next?

Anthony Reeve.

LASSCO Three Pigeons

- A Second run of panelling from the Mauretania, believed to be from the entrance lobby on the same deck is also available and will be catalogued soon.

- *Charles Mellier & Co. were a top-notch cabinet-makers and upholsterers. The firm was established in Frith St. Soho. London by 1871 by Charles Louis Meiller b. c 1827-1887 and his son Charles Eugene Mellier 1859-c.1891. Charles the Elder had emigrated from Paris in the 1850’s and specialised in French interiors; by the late 1880’s the firm employed over 150men. The business survived Charles Eugene and is known to have formed a number of partnerships over the years and moved premises a few times in Marylebone, Cavendish Square and ultimately Hanover Square. The business name was still in use until the mid 1930’s.