The Eton College Museum Chimneypiece

Salvaged from under the floorboards of the school hall at Eton, where it had lain for 88 years, LASSCO has acquired a spectacular stone fireplace:

In 1935, faced with the dismantling of a huge stone fireplace in the Classical Museum at Eton College, the builders were clearly daunted. Even when disassembled into its component parts – keystone, corner blocks, shelf, jambs, foot-blocks – the stones they were handling were both massive and delicately carved. Getting it all down was one thing. Getting it out of the building was another. So, instructed to store it for safekeeping, it was agreed with the college that they might lower it into a crawl-space below the school-hall floorboards a few yards away. They slid each large section down there, arranged it on its back in the correct order, replaced the floorboards, and there it stayed.

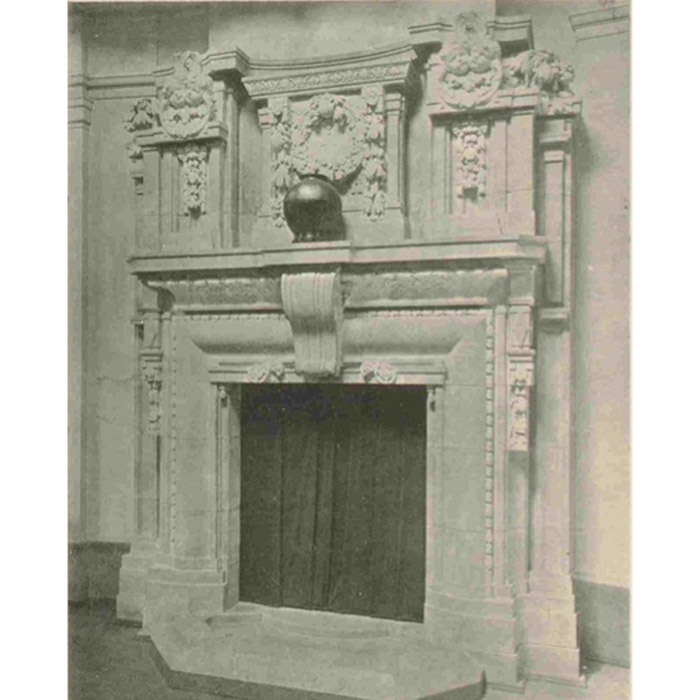

The stone fireplace is colossal, and it is beautifully carved. The shelf has acanthus leaves scrolling out from underneath its edge hiding clusters of flowers, the keystone has floral tendrils working up the sides. The jambs are trimmed with repeating foliate mouldings, some small hanging “guttae” in the corners and some unusual pendant ornaments that are squared-off, they terminate abruptly – as if snipped-off. All this was carved by hand in the stone fireplace; similar ornament is also found, by the same hand, in the detailing of the building in which it was interred.

No doubt over the years since, hushed boys, boarders on quiet Sunday afternoons exploring the forbidden parts of the school buildings, would have fallen upon this hidden giant by torch-light and wondered at why it was there on its back in the dark and the dust, and would have marvelled at the beautiful ancient carving on their archaeological find. In fact it had had quite a short life before it was entombed all those years ago – when it was taken down it was only 30years old.

*

On a summer’s evening in July 1902 the Rev Dr. Edmund Warre, Headmaster of Eton had pushed back his chair and rose to his feet in order to address the assembled gentlemen – the Provost and Governors of the school – a distinguished group of old Etonians who had assembled at The Mansion House. They had come together to agree on a suitable Memorial to honour the boys of Eton who had fallen in “The South Africa War” that, thankfully, had just come to an end. The Second Boer War had claimed the lives of 129 pupils from the school. The motion had been passed and it was determined that the memorial should take the form of a Building. Warre wanted to steer the funds towards a Building that would best serve the school:

“With regard to the memorial hall, the idea of which has been attributed to a certain extent to myself, ever since I have been headmaster – nearly eighteen years – I have been wishing to have a place where we can gather the whole school together either to hear the headmaster or some important person, such as a statesman or a soldier, who would wish to see all the boys, and all the boys to see him.

The place should be a glorious place, where the busts and portraits of old and eminent Etonians can be placed.

But it is not the hall only that I wish to plead for, though I am sure if this meeting will do what I hope it will do, that it will be the pride and glory of future generations of Etonians. I wish also to plead for the school library which is very greatly needed. It is now in two small rooms which I want badly for schoolrooms, and it is not a dignified place for the number of boys who want to read….”

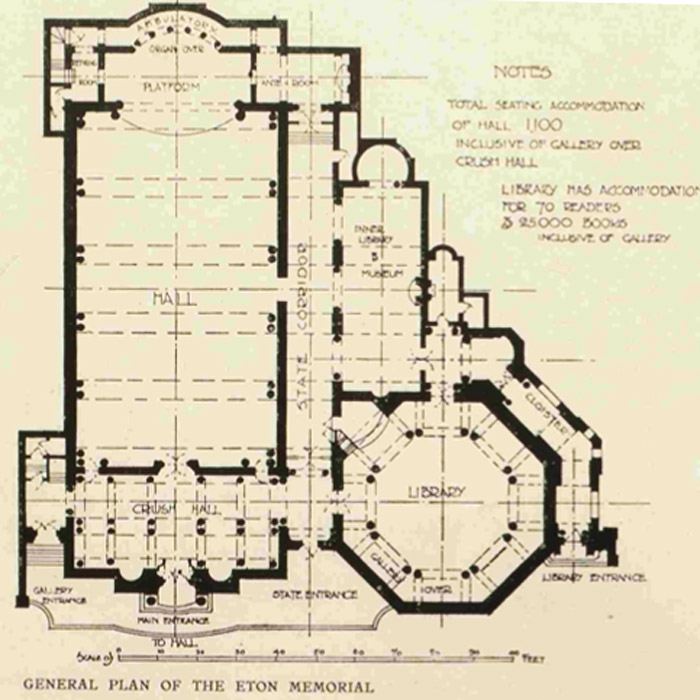

The Rev Warre clearly had some clout: by the time the long meeting was concluded, a “Committee of Taste” had been appointed to run the project and the scope of the works for the Memorial Buildings, to be passed to the yet-appointed architect, included “a hall to seat at least 1100persons, a school library and a small classical museum”.

Norman Shaw RIBA, was to oversee a competition for the best design for the complex of buildings; they were to occupy a triangular site on a corner of the street at the heart of the school and directly opposite the famous chapel and ancient dormitories. Two Georgian houses, “Woolly-Dodd’s” and “Drury’s” were to be flattened and some more land purchased in order to squeeze it in. Shaw and his committee ultimately chose the design by Laurence K. Hall F.R.I.B.A, himself an old Etonian, and Sidney K. Greenslade A.R.I.B.A.

Hall and Greenslade’s plan – somewhat amended by the committee – was a cleverly articulated treatment of the difficult site. The resultant school hall was large and airy with a crush lobby at the front and a minstrel’s gallery above it. The library was separate, octagonal in plan, with a domed roof not dis-similar in format to the Radcliffe Camera in Oxford. Between the two, a large rectangular colonnaded space was included – this was for “The Classical Museum”.

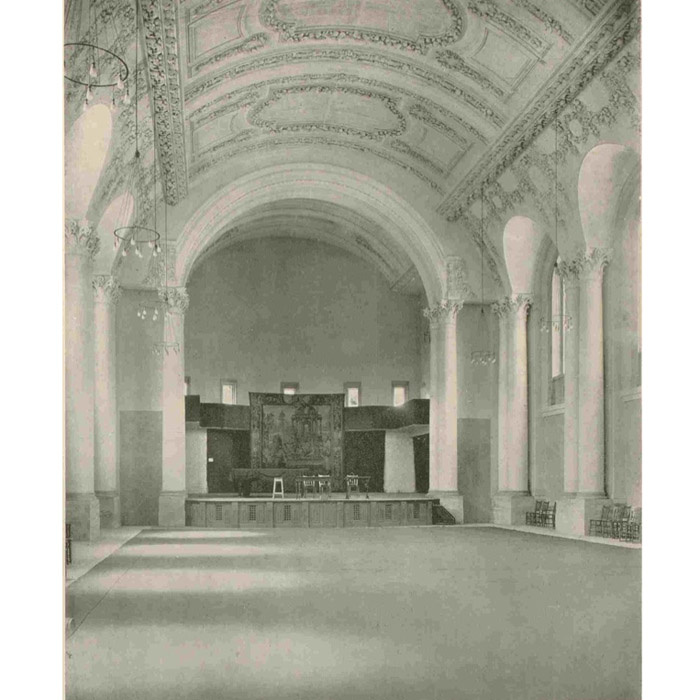

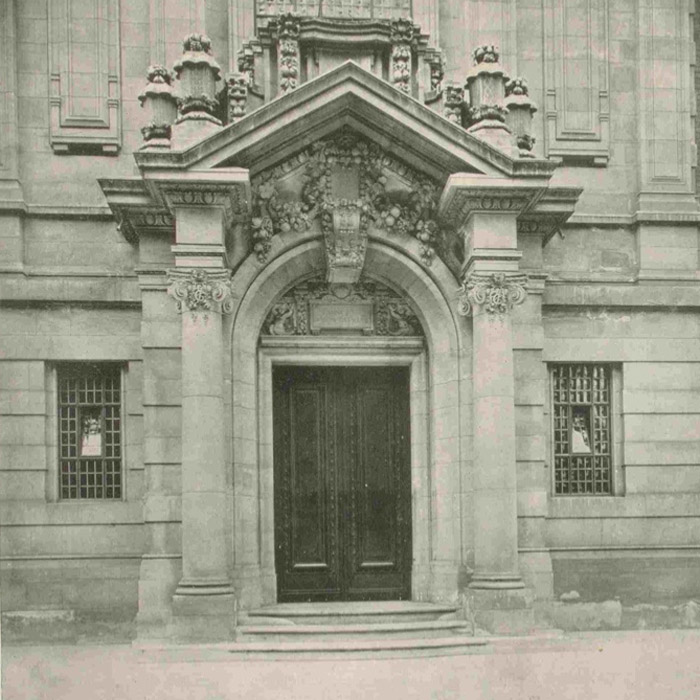

The buildings were fabulously appointed – in the Hall a barrel-vaulted ceiling with rich stucco work held aloft – along each interior flank – with huge pairs of pink marble columns, their intervals forming arcades for large windows. The exterior was fronted with a grand Portland Stone doorcase: a broken triangular pediment centred with a heavy keystone embellished with swags of fruit, its top seemingly crowded with urns.

The Memorial Buildings were opened by King Edward VII on 18th November 1908 – he arrived by open landau from Windsor Castle and his visit was announced in The Times that day where the new buildings were reviewed:

“The ceilings of the hall and library are worthy of notice. They are of cast fibrous plaster, modelled by Mr Arthur [Sic.] Broadbent from designs by the architects. Both in the stone carving and in the plaster work an attempt has been made to revive the spirit of the work of Wren and Grinling Gibbons. The buildings generally are designed in the style of the English Renaissance of that period. Externally, Portland stone has been used in conjunction with a purple grey brick very similar to that used by Wren elsewhere”

The Memorial plaques, together with the Foundation Stone and a Roll of Honour were central to the Hall together with a bust of Queen Victoria. A large new circular oak table was central to the domed Library, at which could sit some of the intended sixty readers. And the giant carved stone fireplace, emulating the doorcase out front, was the centrepiece of the Classical Museum.

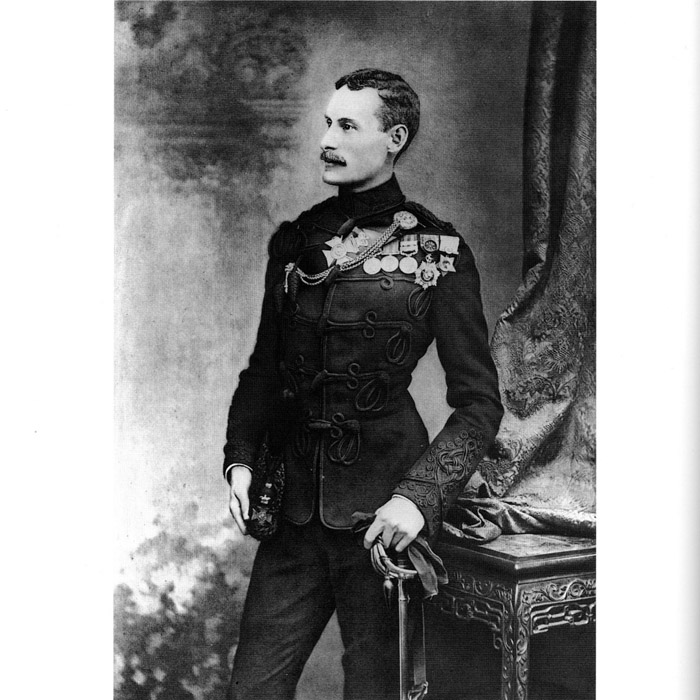

The Classical Museum (later referred to as “The Myer’s Museum”) was also central to the Boer War Memorial theme. Major William J. Myers O.E (1858-99) had studied at Eton from 1871-5 before going to Sandhurst; action in the Zulu War followed and then a posting to Cairo. There he fell-in with Emile Brugsch, assistant curator of the Bulaq Museum and, with trips up the Nile to follow, his lifelong obsession with ancient Egypt was born. He became an avid collector of ancient Egyptian artifacts, always in touch with his mentor Brugsch, and returned to Egypt on numerous occasions, becoming known as a discerning buyer and an authority on archaeological finds. His collection grew and though it was decidedly aesthetically driven rather than academic, it became an important one. In 1999 the Myers Collection was exhibited at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York – the accompanying catalogue describes the collection as “one of the finest collections of ancient Egyptian decorative arts”.

Myers retired from the army in 1894. His comprehensive diaries (unpublished) reveal the great love he had for Eton – his house “Willowbrook” was in the town. Headmaster Warre ensured Myers’ link to the college was maintained when he invited him to become Adjutant to the Eton College Rifle Volunteers in 1898. Myers’ travels continued and he would delight in showing his Egyptian archeological acquisitions to the boys of the Eton Rifles on each return. In 1899, when war broke out in Natal, he volunteered to rejoin his former regiment in South Africa. He was killed in action at the Battle of Ladysmith on 30th October within four days of arriving in South Africa. The news of his death was a profound shock at Eton.

In his will Myers bequeathed his exquisite collection to Eton in perpetuity. It joined the Copeland Collection accessioned in 1897 and as per his instructions was chosen from his own cabinets at Willowbrook by M.D.Hill, then Curator. Other bequests to the museum were to follow, including one from the Duke of Newcastle in 1917.

Headmaster Warre, a distraught friend and admirer of the late Myers was a key proponent of the inclusion of the Classical Museum in the new buildings. Myers’ brother, Sir Dudley Myers, urged the Provost and Fellows to accept its inclusion at The Mansion House meeting.

In the 1960’s G.A.D.Tait, then curator of the collection, remembered the original Classical Museum as “an open stone-lined space containing cases varnished black, with the antiquities crowded on boards covered with red baize”. We are yet to find an image showing the huge fireplace within the context of the Classical Museum, but it must have loomed magnificently. We have one picture of it as published in the Architectural Review in 1907.

The Memorial Buildings complex was all built by Henry Willcock & Co of Wolverhampton – they came in on budget. The metalwork, including the lead urns atop the library dome, was supplied by both the Singer Foundry in Frome and Thomas Elsley in London. The library woodwork was supplied by Ogilvie’s of Inverness. And, as mentioned by The Times on opening day, the spectacular stone carving that embellished the whole complex – inside and out and included the grand doorcase and the Museum fireplace was executed by Abraham Broadbent (1868-1919) (Broadbent is repeatedly referred to as “Arthur” in a lot of the source material but, either this was a preferred name of the sculptor – or it was an error that was mistakenly propagated by The Architectural Review in 1907). A 1912 report at The City and Guilds had it that Broadbent “has arrived at the acknowledged position of being one of our first architectural sculptors”. He was by then exhibiting widely. Some of his best figural work, a commission for Aston Webb at South Kensington, can be seen on the facades of The Victoria and Albert Museum today. Another work was for the Union Government buildings at Pretoria. For architectural stonework he was well known as an English Baroque specialist.

Such was the scale of the stonework at Eton that Broadbent was given a section of the G.W.R goods yard at Windsor as his workshop – in order he could have space enough to take delivery, lay out, cut and carve the blocks supplied to him by The Bath Stone Firm.

*

Today’s Librarian at Eton still wonders whether the Memorial Buildings presented a bit of an awkward problem for the College in the early 1920’s. Whilst it so deservedly memorialised the 129 boys that had fallen in the Boer War, how could they then proportionately memorialise the 1,158 boys who fell in The Great War? It was a conflicted issue that they could not have foreseen in 1902.

A solution to this conundrum, in part, was provided some time later, in 1934, by the approach of Sir Eugen Millington-Drake who had been a pupil at Eton from 1901-08 (so had presumably attended the opening ceremony of the Memorial Buildings in 1908). Millington-Drake was moved to establish a memorial to the 53 fellow pupils of his house, as well as eight other friends, who had been killed in the trenches. He proposed an extension to the Library, housing Millington-Drake’s own collection of books; it would be named after the late Vice-Provost Hugh Macnaghton, the much-loved house master of these boys. The books were a unique collection of volumes all relating to the Great War, many signed and with correspondence – Millington-Drake was a diplomat and was part of the British team at The Paris Peace Conference of 1919-20.

It was resolved that the Classical Museum should be moved – it was relocated to a new dedicated extension at the back of the Hall. The room it had occupied was re-formatted as The Macnaghton Library. The Museum that had been open to the corridor alongside the main hall – separated only with a colonnade – was walled-in. And this was when the large fireplace was removed together with a row of pedestals that had lined the corridor. Some of the decorative overmantel of the fireplace was incorporated into doorways on the way to the new museum but the rest needed storing and the builders were not keen to carry it too far. It all ended-up under the floorboards.

*

Eighty-eight years later and the Memorial Hall has just undergone a spectacular renovation. A singular donation to the school has enabled the Hall to be transformed into a world-class auditorium. Being a Listed building, the College submitted initial plans to the local authority seeking to turn the flat hall into a raked auditorium. The planners said no. With a fair degree of blue-sky thinking, more plans were submitted: there sure-enough was the flat floor – except it had an ingenious amendment – hit a button and the whole floor, now mounted on large hydraulic rams, can be tilted-up for performances; a bold and brilliant solution. The planners approved. The hidden fireplace needed to find a new home.

LASSCO has bought the fireplace, extracted it and re-built it at LASSCO Three Pigeons. It is the first time it has been built upright for 88years. It can be found listed on our website here.

Anthony Reeve

LASSCO Three Pigeons