Ironwork from the Greatest Forgotten Wall in London

Sir George Gilbert Scott’s dramatic Midland Grand Hotel – later known as St. Pancras Chambers and now St. Pancras Renaissance Hotel – is a vast Gothic architectural masterpiece. It dominated the skyline along The Euston Road in Victorian London. It was built by The Midland Railway and was completed by 1873. The terminus complex, comprising Scott’s 400 room hotel and the colossal train-shed, that spanned the St. Pancras platforms in a single arc, was quickly a success for The Midland Railway. However it soon became clear that London’s insatiable need for goods, especially coal and fresh produce – fruit, vegetables and milk – meant that the goods yard that The Midland had built further to the north in Camden was simply not big enough. It couldn’t cope with the sheer volume of freight coming in.

A bold scheme was put forward: to clear “Agar Town”, the crowded slum-houses to the west of St. Pancras. It would enable a large goods yard for receipt and distribution of freight using the Midland main-line. The area, since it had been sub-let by William Agar in 1831, had evolved into a notorious shanty town. In 1851 Charles Dickens described it as:

“A complete bog of mud and filth with deep cart-ruts, wretched hovels, the doors blocked up with mud, heaps of ashes, oyster shells and decayed vegetables. The stench of a rainy morning is enough to knock down a bullock”.

Parliamentary Powers were obtained by an Act of 1875 – the land was acquired from Earl Somers in 1877 – and the poor residents, survivors of an horrendous cholera outbreak a few years previously, were given their marching orders. In 1883, The Midland Railway let the contract to Joseph Firbank (1818-1886) for construction work to commence.

Firbank was a prolific railway builder. Born in the North-East he had settled in Newport in south Wales where he had built and maintained the Monmouthshire Railway. He took on track-laying and heavy engineering projects nationwide. Under him, the design for the Somers Town Goods Depot was drawn-up by The Midland Railway Chief Engineer: John Underwood.

An ambitious two-deck goods yard was designed. St Pancras differs from neighbouring King’s Cross to the east in that the tracks and platforms are raised. This solution enabled the tracks to traverse above the Regents Canal to the north and arrive at their terminus before the Euston Road at that high level (conversely, the Great Northern Railway tracks to Kings Cross tunnelled underneath the canal and stayed low). The tracks and sidings to the new Somers Town Goods Yard to the west were to branch from the mainline as it crossed the canal and terminate before the Euston Road at the same high level. Beneath, loading bays were envisioned – a logistics hub for triage, trade and distribution on to the horse-drawn road network. With its own independent hydraulic system, 20ton loaded railway wagons could be dropped to the lower level on lifts for unloading.

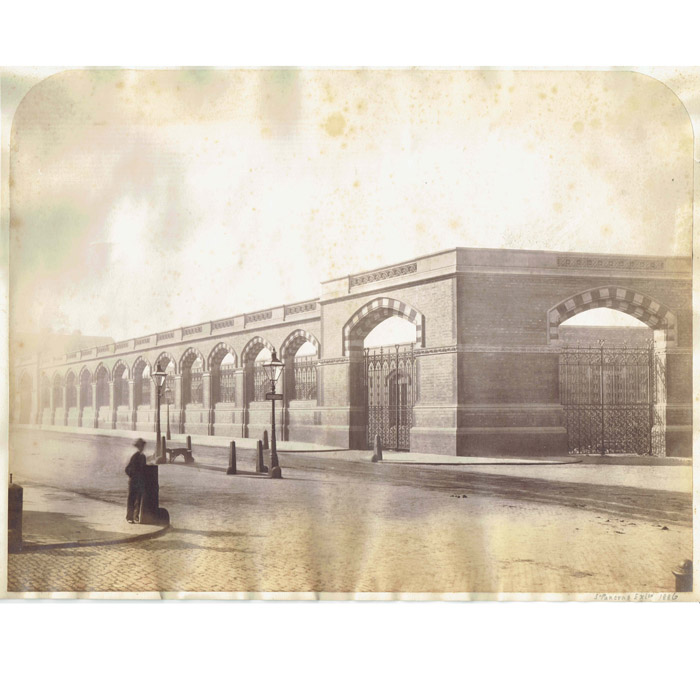

The design, whilst technically brilliant, was also carefully considered aesthetically – to compliment Sir George Gilbert Scott’s passenger terminus next door. A vast decorative screen wall would contain and secure the goods depot – necessarily tall to both encompass the raised sidings within, and the perimeter access roadway around them, but essentially horizontal in format – emphasising the soaring vertical spires of The Midland Grand Hotel beyond.

The construction of the screen wall is described in “The Life & Work of Joseph Firbank J.P. D.L – Railway Contractor” by Frederick McDermott:

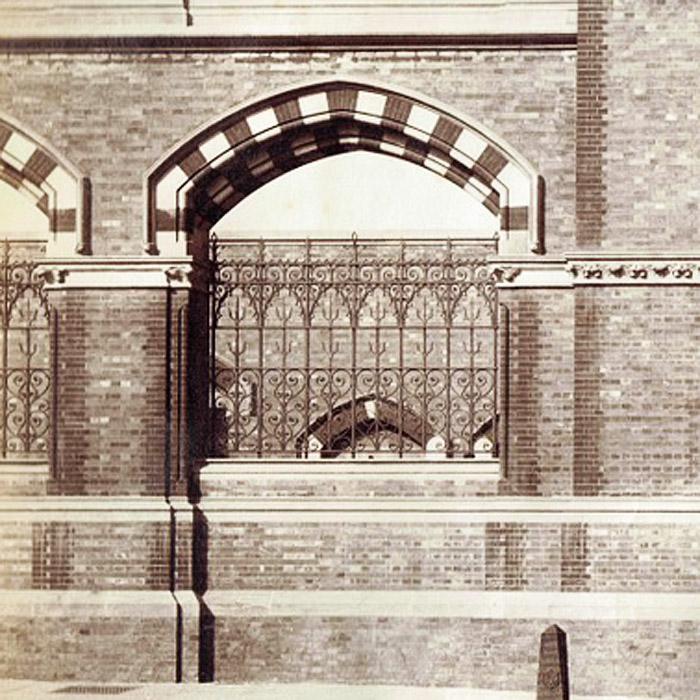

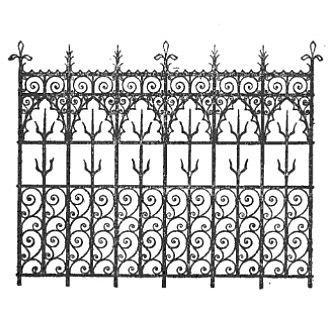

“One of the first works taken in hand was the magnificent screen wall, 3250 feet or about three-quarters of a mile in length, 30 feet high and nearly 3 feet thick, which surrounds the entire site. This magnificent piece of brickwork, probably the finest in the Metropolis, required about 8,000,000 bricks of a peculiarly small size, rising only 11 inches in four courses, which greatly improves the appearance of the work. It is faced with Leicestershire red brick, the inner portion being entirely of Staffordshire blue bricks, set in cement, no lime having been used in this or any other work on the depot. Had the engineers of the Midland Company intended to rival the Great Wall of China, or provide a citadel for the Metropolis in the case of invasion, they could hardly have devised a more imposing structure. The elevation on the Euston Road is tastefully ornamented with Mansfield stone, whilst the large arched openings, left in the wall to assist in lighting the roadway which runs around the enclosure, are protected by hammered iron screens, 11 feet by 8 feet, and weighing about 12 cwt. Each, of beautiful workmanship.”

“The Life & Work of Joseph Firbank J.P. D.L – Railway Contractor”

Frederick McDermott 1887

A salvaged section of this screen ironwork, found by LASSCO in an artist’s studio in Kent, is one of these panels – as illustrated with a photograph and line drawing in the Firbank biography. It is available for sale at LASSCO here. [nb. The railing has now Sold].

Next door Sir George Gilbert Scott had gone to Francis Skidmore of Coventry for his ironwork – including the spectacular staircase – he always used Skidmore. The Somers Town panels do nod to the Hotel ironwork in terms of design but we have not found evidence that they were made by Skidmore. Another likely contender is of course the St. Pancras Ironworks – research continues.

Firbank died on 29th June 1886 (the above biography was published the following year) with the vast construction project still with 18months to run. The reins were passed to his trusted deputy J. Throssel to complete.

***

Behind its screen wall, for the next century, Somers Town Goods Yard was a vital hub for supplying the capital with produce and fuel. In its heyday the relentless arrival of goods kept 1200 rail company horses busy as they pulled an endless stream of loaded carts out onto the cobbled Euston Road for onward delivery. Six hundred railway wagons could be handled at any one point in a sophisticated network of sidings, turntables and lifts. By 1900 2.4million tons of coal was being distributed through this yard each year.

A prime infrastructure target, Somers Town Goods Yard took several hits from above in both World Wars. The damage, including to the magnificent screen wall, was quickly repaired but after the second war with competition from road hauliers and motorways, the demise of coal fires and the rise of the supermarkets the Somers Town Goods Yard started to decline.

As Ian Mansfield describes in his London History blog site:

“The 1960’s were not kind to London’s Victorian heritage. Soot-encrusted and neglected, such buildings were seen as old-fashioned grotesques that had lingered too long. The decline in rail travel made stations particularly vulnerable to modernising drives. Despite public outcry Euston’s elegant Doric buildings fell in 1961-62, and by 1966 it was clear that St Pancras was next in the firing line. Yet the shockwaves of Euston’s demolition had galvanised opposition, and this time British Rail found itself facing an influential alliance of critics. … By 1967 the complex had Grade I protection… St. Pancras was saved”

from “Ian Visits” a blogpost by Ian Mansfield

Ian Mansfield continues in his blog post (during the 2013 archeological dig by The Museum of London at the site):

“Although it did not have the High Victorian grandeur of St. Pancras, the Goods Yard proudly echoed its neighbour’s opulence with understated arcades of Gothic brick arches. St. Pancras may well deserve to be lauded as a Victorian cathedral of steam, but Somers Town was its essential counterpart: a temple to consumerism on a massive scale. The goods yard however could not muster a line up of poets … [i.e Betjeman]… and architectural historians to shield it from the wrecker’s ball. So while St. Pancras was spared, its unsung adjunct was levelled.”

The British Library was built on the site in 1997.

We have found some commendable instances of re-use of some of the ironwork salvaged from the Somers Town Goods Yard demolition. One of the pairs of large gates that gave access through the screen wall from The Euston Road have been hung as the entrance to the “Camley Street Natural Park” found sandwiched between the embanked Eurostar platforms and the curve of the Regents Canal to the north of St. Pancras. Another smaller pair, matching those, is found at the foot of the steps from the raised concourse of the hotel down to St. Pancras Way. The screen for sale at LASSCO could be converted to similar gates.

An afterthought:

The Somers Town Goods Yard was a vital hub for the distribution of goods – mainlining straight from the east Midlands into the heart of London. Today, the efforts to alleviate pollution and traffic congestion on the roads include Congestion Charging and Emission Zone restrictions. Surely today’s Mayor of London, as well as the likes of Amazon, must look ruefully at the brilliant Victorian logistics solution detailed above that had brought vast quantities of goods into central London on-rails-not-road for over a century. It was a solution that was tragically scrapped and was contained in a vast and very handsome building that has been demolished and is almost completely forgotten.

Anthony Reeve

LASSCO Three Pigeons