Salvaged From Obscurity – Half A Century On.

LASSCO has unearthed a large batch of decorative tiles from an historic London architectural gem, long thought lost without a trace.

‘Southampton Buildings’, headquarters of the Birkbeck Bank, stood between High Holborn and Chancery Lane between 1896 and 1964. The vast Victorian banking hall was built in two years by T.R. Knightley and Co. At the time of its construction it was one of the very first buildings in the country to employ the new steel framed construction techniques developed in the United States. In this sense it was radically pioneering and its construction convinced the LCC to pass a 1909 building act explicitly permitting steel framed construction in London – for which the ‘Shard’ and ‘The Gherkin’ may wish to express their gratitude.

The architects of the bank made full use of the fortuitous developments in architectural ceramics underway at the Royal Doulton Lambeth factory to embellish their project. In 1871 Henry Doulton, anticipating the Arts and Crafts movement of a decade later, began enrolling young apprentice potters from the Lambeth School of Art at his family pottery works, with a view to developing hard glazed decorative ceramics. The ubiquity of Doultonware still extant in London – from Underground stations to Public Baths, private dwellings and chapel buildings – is a testament to the diversity and quality of design that poured out of the Lambeth works.

The exterior of the Birkbeck Bank was faced in fantastical pale ‘Carraraware‘ ceramic peaks and finials. The brilliantly glazed cornices, mouldings and exuberant mannerist details formed a dazzling exposition of the architectural potter’s craft. The interior of of the bank was described by Pevsner as expressing ‘a riot of Majolica’ with patterned and coloured tiling throughout. The central banking hall, faced in brilliant polychromatic Doultonware, must have dazzled as it rose into a cavernous rotunda above the circular central desk.

Despite protests from conservationists the bank was demolished in its entirety in 1964. Its replacement on Holborn was a low rise concrete office block, a form much favoured of the period.

The demolition was widely recognised as a disgrace at the time. The gratuitous destruction of the building was shameful not merely for its lack of respect for the built environment but further because the lost tiling and ceramics created by Doulton for the building were an authentic display of creative talent from the London artisan class. Despite the striking photographic record afforded by the studio of Bedford Lemere, taken before demolition commenced, it seemed as if the dazzling Doultonware ceramics were lost forever in the rubble.

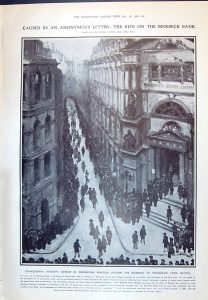

In one melancholy episode, however, the bank can be said to live on. A ruinous and widely publicised ‘bank-run’ in 1906 caused by a single anonymous letter led to the complete collapse of the savings bank in one day. The bank was later amalgamated and continued trading till its final closure in 1964. The incident made global headlines at the time, in the classical period of print journalism, and is said to have inspired the famous ‘bank-run’ in the film Mary Poppins.

In spite of the seeming total destruction of this ebullient capriccio of a building LASSCO has, 50 years on, managed to rescue and restore a small hoard of original tiles from the central banking hall and is pleased to offer them for re-use. The finer Doulton Lambeth made tiles are mixed in with later Burslem reproductions. Both sets of tiles were rescued by a sympathetic builder at the time of the 60’s demolition and have passed through various hands till they were discovered, fully provenanced in a shed in Gipsy Hill by LASSCO Peony and roundel tiles available.

Save