ST. MICHAEL AND ALL ANGELS’ CHURCH, SHOREDITCH: LASSCO’S HOME 1979-2007

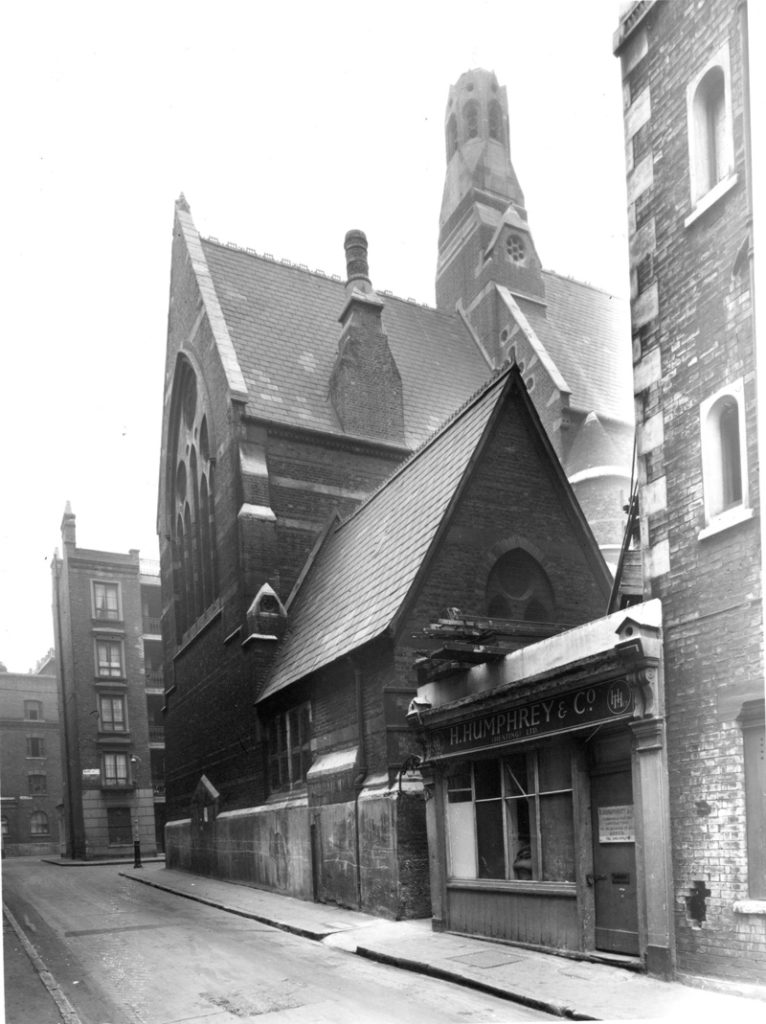

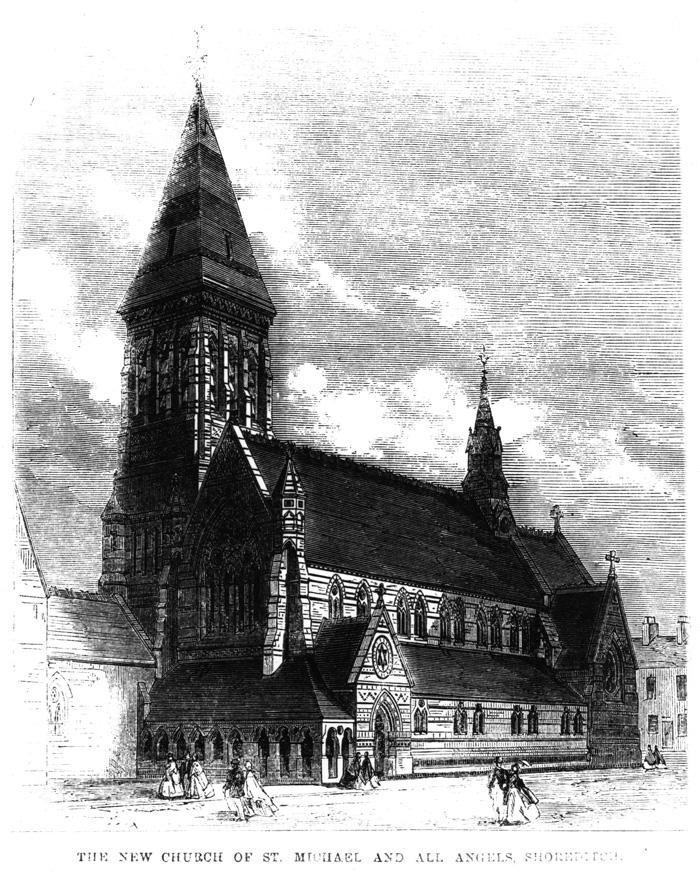

St. Michael & All Angels Church in Shoreditch, London EC2 was the home of LASSCO from 1979 until 2007. We were “that Architectural Salvage place in that church in East London”. It is tucked into the rabbit warren of Victorian streets that form a triangle south of where Great Eastern Street leaves the Old Street roundabout and heads towards Spitalfields. St. Michael’s is a cavernous church and splendidly appointed with fine polychrome brickwork, stone detailing and notable stained glass.

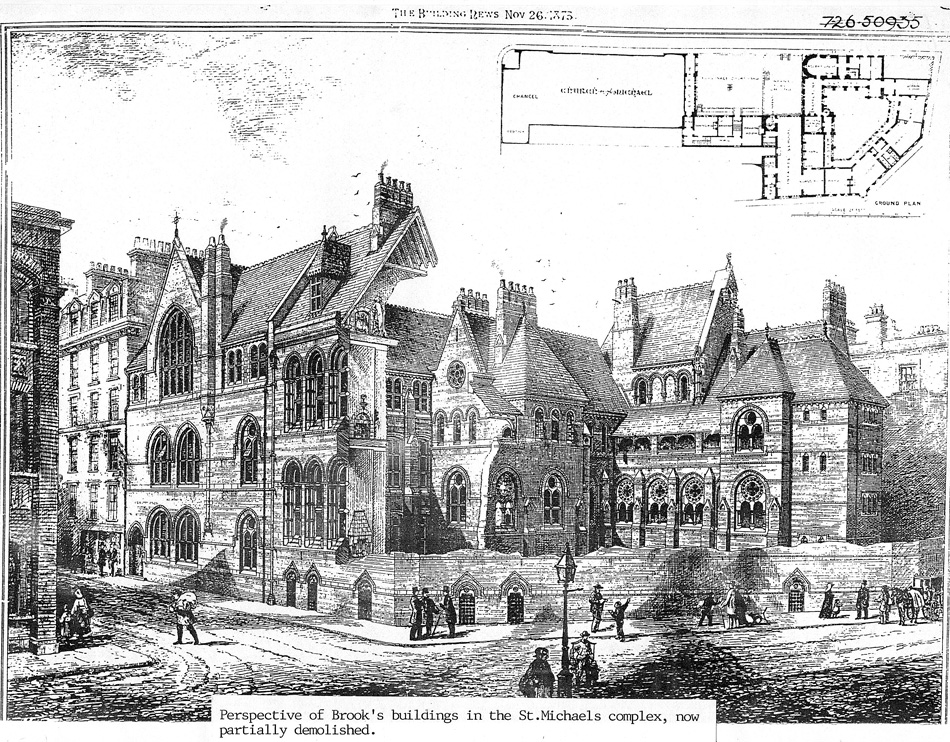

Completed in 1865 it was the first major church project by James Brooks (1825-1901). The church forms part of an ambitious group of ecclesiastical buildings that have, with the exception of Brook’s convent (completed by J.D.Seddon), survived the ravages of progress in one of the most frenetic areas on the northern fringe of The City. Pevsner described it as “eminently picturesque” group, notes the influence of Butterfield and particularly liked the “excellent” East window by Clayton & Bell.

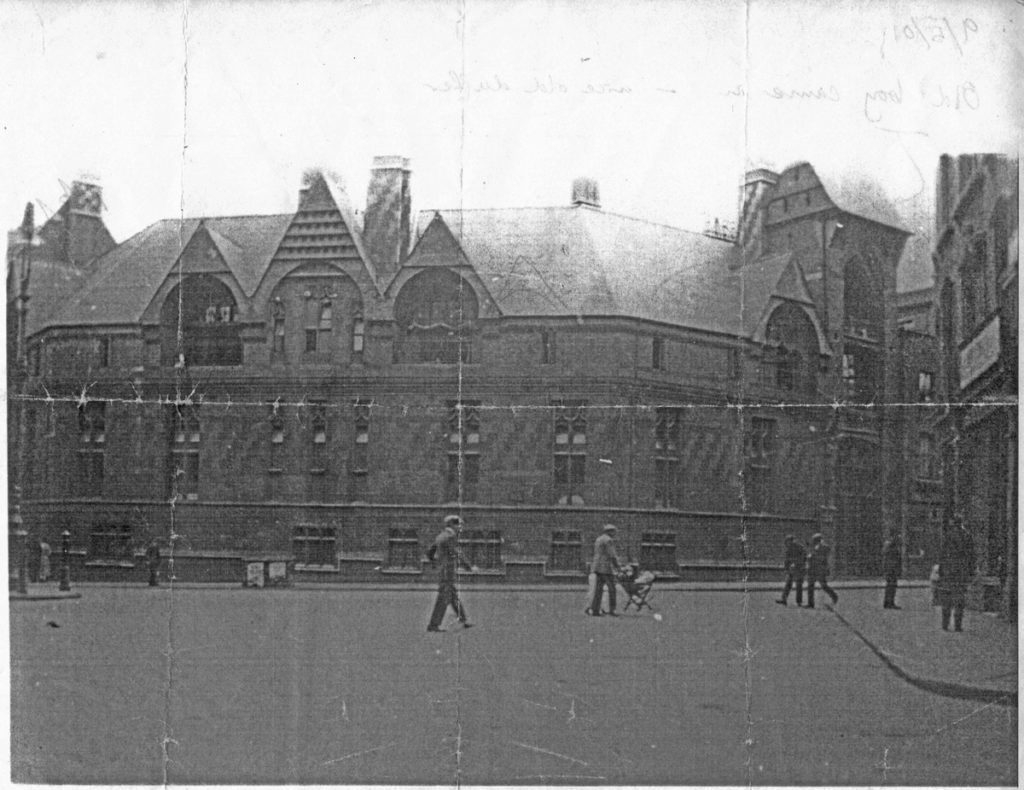

On its purchase from the diocese in 1978, the church, its Clergy House and School House were in a poor state of repair – the congregation had long since moved away with most of the Victorian tenements of the area having been demolished. The handsome nave had ultimately been designated as a storage warehouse since 1964.

LASSCO and Westland & Company jointly took on the occupation of the space with glee and ensured that the building was made water-tight and, as time went on, sensitively restored. A floating mezzanine was added internally and it quickly became a famous Architectural Salvage emporium – both in the nave and in the yard outside.

Shoreditch, in the early 1980’s, had a very different reputation to today; then it was a byword for dereliction. Cabinet makers and veneer dealerships still clung-on along Curtain Road, printing firms occupied the warehouses, but it was all very run-down. Tramps still lived behind the advertising hoardings.

But Shoreditch was due for an extraordinary revival and we watched the transformation going on around us as Hoxton Square became central to what The New Yorker then described as “the hottest postcode in the universe”. The Square Mile with its overbearing glass towers seemed to be steadily marching up Bishopsgate towards the church. And it still is.

St. Michael’s now finds itself in a salubrious neighbourhood – James Brooks would never have envisioned it.

Below, notes from a Survey by Paul Joyce of The Victorian Society concerning the work of James Brooks. We have inserted images from our own files.

***

Churches by James Brooks in Shoreditch

18th July 1992

INTRODUCTION

James Brooks (1825-1901) was born at Hatford near Wantage in Berkshire, the son of a farmer. Sent to study at nearby Abingdon Grammar School, he came into contact with Dr Pusey and other prominent High Churchmen of the locality. Through their influence he abandoned planned for a career in farming and turned to architecture instead. Aged 22, he arrived in London in 1847 to become articled pupil to Lewis Stride; he attended Professor TL Donaldson’s lectures at University College, and in 1849 entered the Royal Academy Schools.

In 1851 Brooks’ independent practice commenced with the modest commission for a Stoke Newington shop front; however the first nine years of his professional life were spare, consisting mainly of domestic jobs in his native county. Oddly enough his earliest church, built 1860, was for nonconformists – a stone geometrical gothic Baptist Chapel in Mill Street, Wantage – and it wasn’t until 1863 that Brooks was given proper opportunity to demonstrate his considerable powers of design on a large scale. That was for St Michael’s Shoreditch, his first important church, and it inaugurated (albeit tardily) the long and distinguished career of this major Victorian High Church architect.

Of the same generation as fellow gothicists Street, Bodley and Burges, James Brooks appears in context to have been a late developer. Married to Emma Martin of Sandford on Thames c1858, he at first set up house in Brixton, moving to his new-built red brick gothic villa at Stoke Newington in 1862. He delayed joining the Ecclesiological Society until 1864, and was elected FRIBA only in 1866. Now in his forties, his reputation was ultimately secured by the remarkable series of large urban churches built for the poor districts of Shoreditch, Haggerston and Hoxton. Here he worked in the characteristic big-boned style which formed the basis of much, if not all, that he did afterwards. In later years he became more integrated into the professional establishment, first taking up membership of Architectural Association in 1884, then serving as Vice President of the RIBA 1892-96: in 1895 he was awarded the RIBA Royal Gold Medal. Unlike his High Victorian contemporaries Street and Burges, Brooks was no great theoretician; indeed some have noted in his character a touch of innocent naivety, but his buildings were bold, original and single-minded. They received their due share of accolades, as from the 1860’s onwards nearly everyone of his significant designs was illustrated in the building journals.

SHOREDITCH PATRONAGE

Brooks’ connection with the Tractarian phase of church extension in Shoreditch began in 1860 with the simple mission church of St Bartholomew, Boston Street, Haggerston. Superseded in 1867 by the parish church of St Augustine, Yorkton Road (designed by Henry Woodyer 1865), St Bartholomew’s was demolished in the 1950’s. It had been commissioned by Rev John Ross, incumbent of St Mary Haggerston, who next turned his attention to his own church. In 1861-62 Brooks remodelled and refitted John Nash’s flimsy Commissioners’ gothic structure of 1825-27, but it was totally wiped out by a landmine in 1941.

After John Ross, the crucial figure was Dr Robert Brett of Stoke Newington, a surgeon and friend of Pusey. Author of a number of religious manuals, from which he devoted the proceeds to church building schemes, Brett had been Butterfield’s client at St Mattias Stoke Newington in 1849-52. Since moving to that district in 1862 Brooks had attended St Mattias and served as churchwarden there 1868-79; he afterwards assisted Brett, who died in 1874, in founding St Faith Stoke Newington (by William Burges 1871-82), and this then became his habitual place of worship.

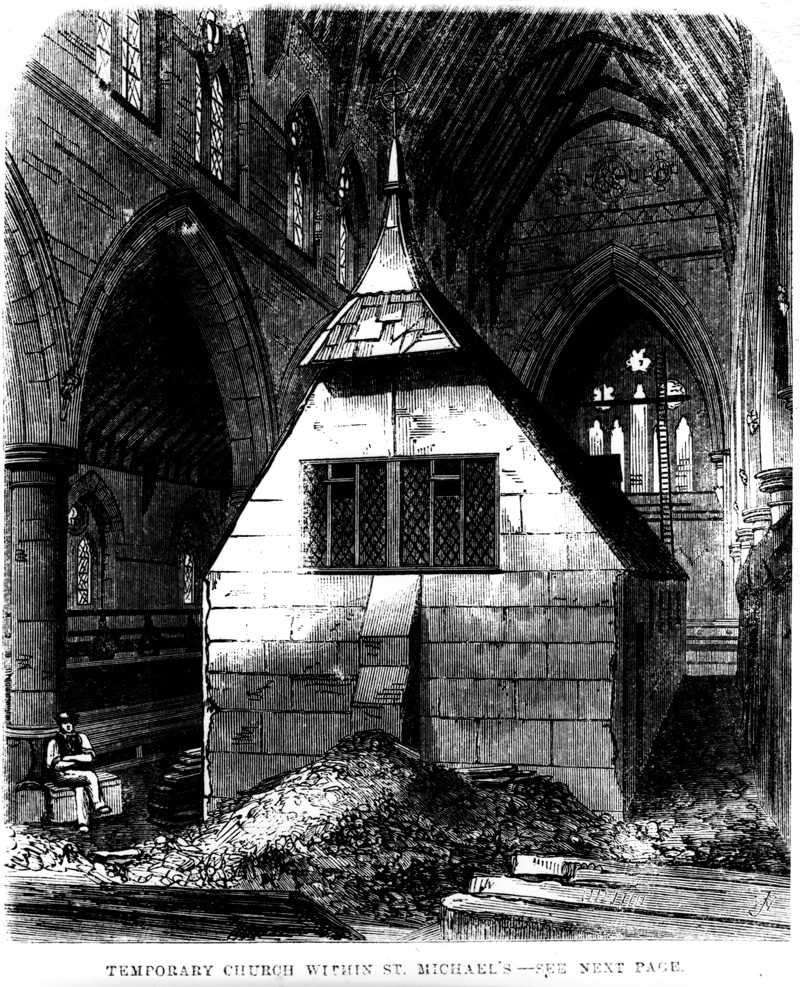

The commission for St Michael’s Shoreditch was obtained through Brett on Behalf of three founders: Rev Thomas Simpson Evans, vicar of St Leonard Shoreditch, Rev John Ross of Haggerston, and a wealthy layman, Richard Foster of Upper Clapton. Brooks first designed a temporary structure in 1862, removed after the permanent church was built around it in 1863-65.

Three further commissions followed from Brett and Foster in 1863-64, of which the vanished St Saviour, Penn Street in Hoxton, designed in the latter year, was the first to be built 1865-66. It was an impressive work in plain red brick, with lofty clerestory and continuous steep roof surmounted by a sharp timber fleche; the chancel, marked only by a change in fenestration, terminated in a sweeping curved apse. St Saviour’s was superficially damaged by bombs in the 1940’s but continued in use until 1953; it was ruthlessly destroyed soon afterwards, together with its attached vicarage of 1873. A preliminary design for St Chad Haggerston was also produced in 1864, but this was put aside until 1867 when a more ambitious cruciform plan was adopted; it was built in 1868-69. Lastly, although sketches for St Columba Haggerston date from 1864 too, the design was worked out in 1867-68 and constructed 1868-71.

THE CHURCHES

These four churches, of which three survive, are remarkable for their stark monumentality and grand proportions, achieved with the simple use of ordinary materials – mainly brick with stone dressings and vast timber roofs. They were extremely cheap in cost for their size, and intended to proclaim the presence of the church in the poor parishes they served. Brooks chose as his model the earliest period of gothic, now however in the archaeological tradition of the Gothic Revival – he was not interested in producing exact copies of mediaeval buildings – but with the limited means at his disposal he created churches for the needs of his own day. Several formative influences are immediately discernible in his stylistic progress: the example of William Butterfield’s London churches was inescapable, and George Edmund Street’s writings on Town churches were equally absorbed. It seems too that Brooks took a long, hard look at John Loughborough Pearson’s recent design for St Peter’s Vauxhall and, like William Burges, opted for the large simplicity of Northern French. In the process of combining these elements at the Shoreditch churches he forged a personal style which he never afterwards surpassed, and which was to serve him well for the remainder of his professional life.

ST MICHAEL AND ALL ANGELS, MARK STREET, SHOREDITCH.

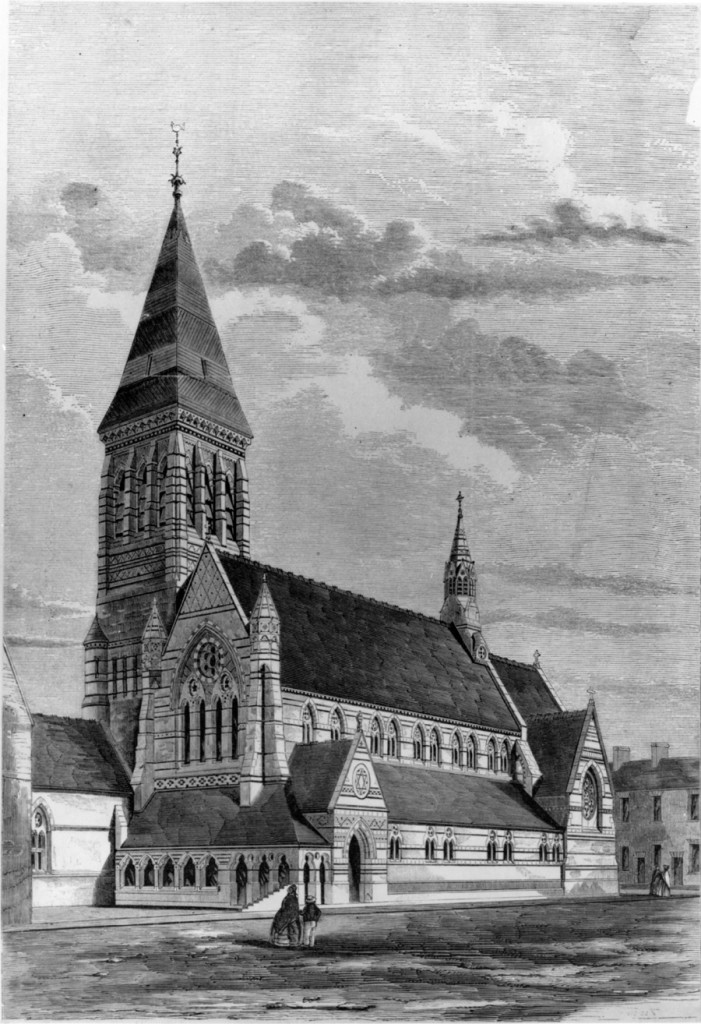

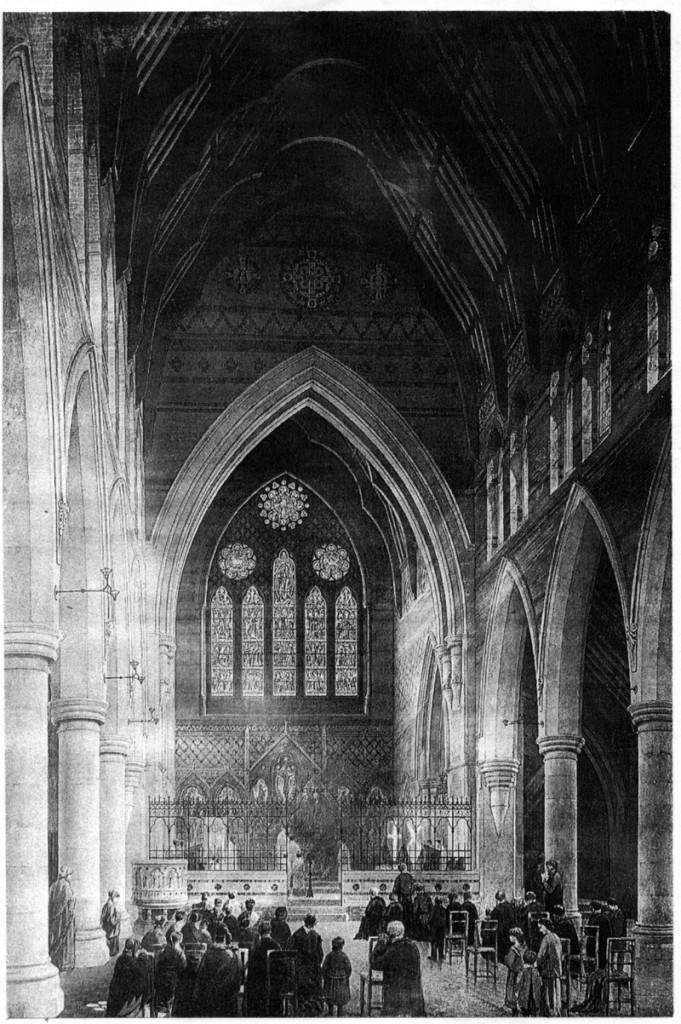

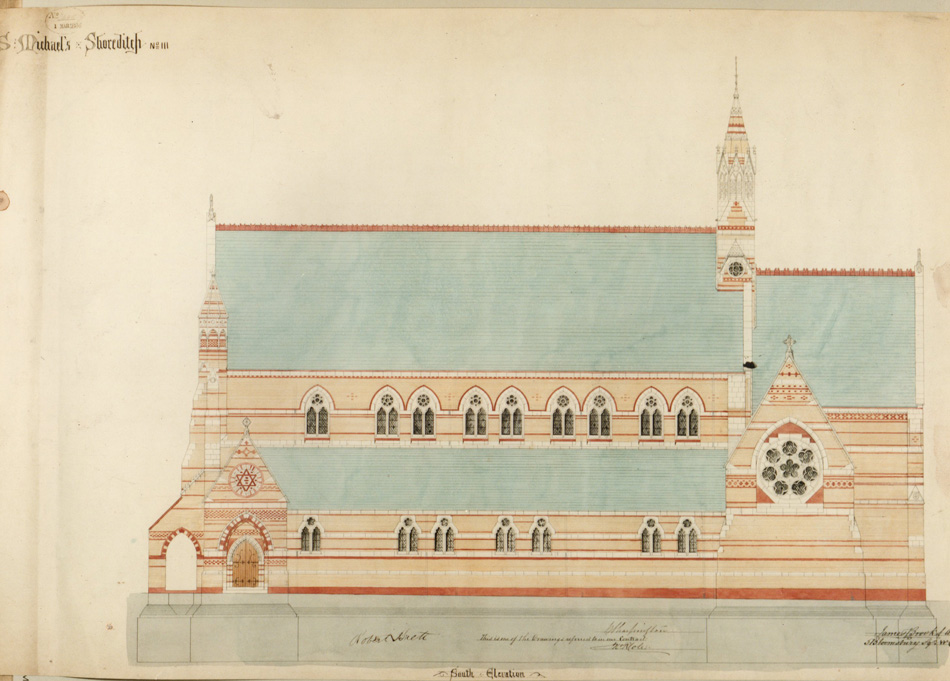

Designed 1863 and built 1863-65 to accommodate 1000; the contract price was £7,180 and the materials yellow brick with red and blue brick bands, stone dressings, and slated open timber roofs. The plan is basically a rectangle divided into nave with clerestory and lean-to aisles, cancel, SE chapel, a N vestry, and a SW porch; there is also an incomplete W narthex. A big NW tower with tall slated pyramid roof was intended but never executed – Brooks was unlucky with towers – however here he played safe and provided an octagonal stone bell turret with spire over the cancel arch, and the W gable is flanked by massive octagonal pinnacles.

Windows are composed of lancets and plate tracery. Internally the proportions are extremely tall and the aisles narrow; stone arcades have circular piers and moulded caps, and over the steep chancel arch are geometrical patterns in coloured bricks. Butterfield is usually cited as the main influence in this somewhat experimental design, but Street is as much in evidence with his more subtle approach to constructional colour. In the event Brooks decided not to repeat this kind of polychromy in his subsequent works. Fittings included a gabled stone reredos with sculpture by Thomas Earp, a wrought metal chancel screen, stone pulpit and font; E window by Clayton and Bell.

A large brick vicarage was added on the N side of the W court in 1867-68, and the school built to its W in 1870. Brooks then completed this ambitious group of buildings with the Convent of St Mary at the Cross 1870-75, attached to the W end of the school; this included a small chapel and a cloister. The front entrance block in Leonard Street was added by JD Sedding in 1880-81. The convent buildings were relinquished in 1931 and demolition eventually followed c.1959.

Made redundant in 1964 St Michael’s is now in commercial use; the group was restored and cleaned in the mid-1980’s when the present setting was created.

Other Churches by James Brooks in the area (Abbreviated):

ST CHAD, NICHOLAS SQUARE, HAGGERSTON

Designed in its present form 1867 and built 1868-69 at a cost of £5,990. The materials are red brick with stone dressings and, following on from the sobriety of St. Saviour Hoxton, there is none of the constructional polychromy that Brooks revelled in at St Michaels’s. The church is a cruciform structure with square pyramid-capped bell turret of timber at the crossing; the four arms are of equal height with steep slated roofs and a semi-circular apse at the E end.

Next to the church, on the S side, is the vicarage of 1873-74.

ST COLUMBA, KINGSLAND ROAD, HAGGERSTON

The final design dates from 1867-68, and was built in 1868-71, the contract being taken for £7,894. Although very economical, this must count alongside the most impressive of all Brooks’ works; grouped as it is with the adjoining vicarage and school, the church makes a dramatic sight. Once more, red brick is the main material and the details are austere early gothic.

The attached vicarage, first sketched out in 1864 and finally designed 1872, was built 1872-73.

Notes by Paul Joyce 1992

With acknowledgements to the late Dr Roger Dixon