No products in the basket.

27th April 2020

Isolation in the East End: A Walking Tour

Searching for ideas on how to spend your daily allowance of exercise – look no further!

A walking guide by Chris Martin.

The tour starts at Hughes Mansions, Vallance Road, at the exact spot where at 7.21am on March 27th, 1941, 134 men and women were killed by the last V2 rocket of the Second World War to hit London. It was cruel punishment to the local Jewish community which comprised around 90% of the populous – 120 of the dead were Jews and the bomb dropped the day before their Passover festival, many of them visitors. The disaster wasn’t reported in the press at the time due to governmental censorship. Two entirely unremarkable blocks of flats were built in the 1950s to replace the demolished 1920s originals to complete the severe, if aesthetically unintimidating estate.

Continuing further south one is struck by the complete lack of architectural interest and it seems this has always the case – on the corner of what is now Lomas Street stood the Whitechapel and Spitalfields Union Workhouse, a gargantuan, relentless and imposing brick building that provided shelter and food for the destitute in exchange for arduous work (for further reading see ‘People of the Abyss’ by Jack London; the American author stayed here). The building later became the Whitechapel Union Infirmary and processed the body of Mary Nicholls, one of Jack the Ripper’s victims, and later became St. Peter’s Hospital which was demolished in the 1960s.

The twenty-five cherry trees at the foot of it are currently in blossom making this possibly the prettiest part of Whitechapel, perhaps not the greatest of accolades. They sit ahead of an interesting early Victorian terrace which was recently saved from demolition by the eager local council by a campaign spearheaded by the East End Preservation Society, a welcome intervention in an area which has suffered so much bomb damage. The buildings in question are currently shrouded in scaffolding but numbers 11 and 13 are still there to be seen. The ground floors remain and the window surrounds on the floors above are embellished with some attractive stonework. Built in 1855 the terrace is the last remaining link to the Pavillion Theatre, the play house just round the corner on Whitechapel High Street which served East Enders from 1827 before shutting its doors in 1934 and being sadly demolished in 1961 – for more information read the excellent Spitalfields Life blog on the topic here.

Looming over the junction with the High Street is surely Whitechapel’s most significant and underrated architectural landmark, the incinerator chimney of the Royal London Hospital. This vast black cylinder stands proud above the rest of the low rise development, an ominous outlet of the hospital’s furnace, burning who knows what. Under its shadow is a small and scruffy terrace of fourth-rate Georgian houses built c.1800, now seemingly in isolation but originally part of a larger development which extended to the High Street and is though to be the original home of Spiegelhalter’s, the clockmakers and jewellers (more on them later).

Continuing further south down New Road one reaches Fieldgate Street, formerly home to the Great Synagogue (now the massive East London Mosque) and a small Gothic mission hall which is now the London Action Resource Centre, an interesting reminder of the anarchist roots of this part of London. These days people usually find themselves here en route to the excellent Pakistani grill house, Tayyabs, but in the future when restaurants are again open, before entering I urge you to take a turn down Parfett Street and Myrdle Street.

In the late eighteenth century the Royal London Hospital (founded 1740) decided to develop the fields that surrounded it in order to assist with its running costs. The hospital’s surveyor John Robinson put together a plan in 1788 for a network of ‘small streets’ to the west of their site. Whilst plenty have been lost to bomb damage and general disrepair, a number of these small and affordable (then, not now) Georgian terraced houses remain in the area, in these streets and across New Road to the east where some beautifully restored examples can be found in Walden Street, Varden Street and Turner Street. Also of architectural note on Myrdle Street are the Edwardian red brick tenement buildings, Fieldgate Mansions, and further down, Myrdle Court, a wonderful Art Deco block of flats (fans of such design should also visit Gwynne House on Turner Street, one minutes walk away) . The vicinity fell in to disrepair after WWII, prostitution was rife and the area attracted large numbers of squatters. Fieldgate Mansions were gradually improved in the early 1980s and The Spitalfields Trust oversaw the fantastic and widely acclaimed restoration of the Georgian properties on Varden and Turner Street.

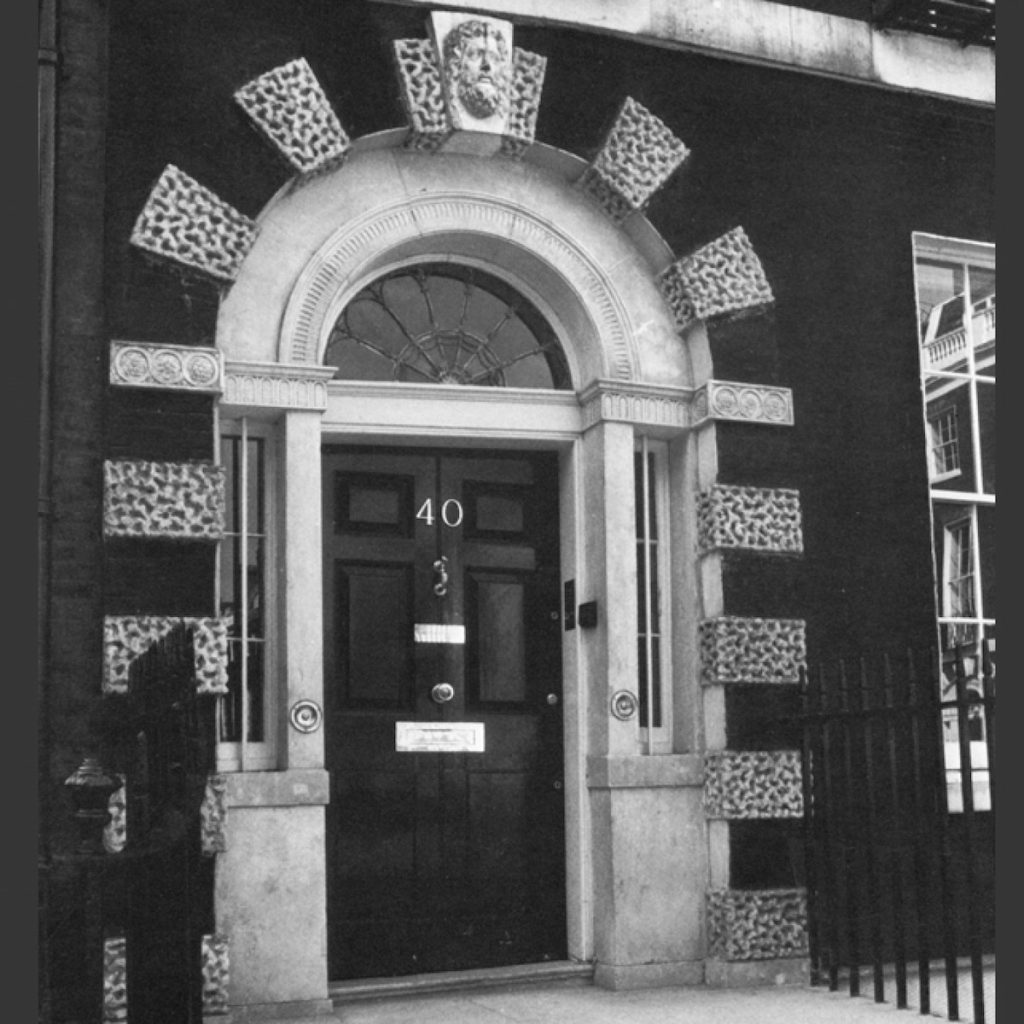

There are a number of slightly grander houses on New Road (formerly Gloucestershire Terrace), a significant thoroughfare that connected Whitechapel, then known as ‘town’s end’, to the Wapping riverside London Docks, constructed in 1799-1815. A number of the more untouched properties have attractive Coade Stone door surrounds which are virtually identical in appearance, if not size, to the Bedford Square door surround LASSCO ourselves cast – link to it here and link to the old LASSCO News Story on the piece here. Whitechapel residents should bask in the smug glory of the comparison as this is surely the first, only and last time the area has been compared to Bedford Square. These buildings date to the very end of eighteenth century and have alternating keystones of a bald and bearded gent (perhaps a monk – similar examples have sold at Christies) and masks of Athena – copies of this keystone and more information on Eleanor Coade can be found here. For those of our readers who are sufficiently well-heeled and for whom a copy of the door surround or keystone is not enough, Number 27 is for sale.

Continuing south down New Road one eventually reaches Cable Street. To the thousands of commuters who cross the junction every day on Cycle Super Highway Number 3, it must appear unremarkable but what if they were to know the story of John Williams, chief suspect of the notorious Radcliffe Highway Murders, whose body lay here?

On December 27th, 1811, crowds gathered for the trial of John Williams who, on very thin evidence was to be tried for the gruesome murders of seven people. Disappointingly, he never turned up, having hanged himself in his cell the night before. The crowds were aghast – Williams had robbed them of a sensational court case, a public hanging and had surely denied the hangman his opportunity to keep the body, clothes and rope, which due to the infamy of Williams would have been worth good money. To allay their mood, the Home Secretary at the time decreed that his body be dragged through the streets and buried at a crossroads. This practice was not unusual, people at the time believed that if the spirit of the dead wished to haunt its former home and foes, the four roads would confuse it. A stake was also driven through his heart to further dissuaded any evil spirits of revenge.

In 1886 workmen laying gas mains discovered the shallow grave of Williams, identifiable by the stake – his skull, by repute, ended up at the Crown & Dolphin pub on the crossroads, now converted to flats. The same practice was observed at The Three Pigeons, the LASSCO country premises where the rascally John Price was executed for the murder of a local lad who actually survived. In Price’s case he was hung in a gibbet at the crossroads.

Cable Street is known as such due to the proliferation of rope making workshops that served the nearby docks and finds itself in an area police deemed no-go until the 1930s. Architectural critic Ian Nairn didn’t think of it in favourable terms and wrote, ‘ ‘Cable Street, the whore’s retreat’: a shameful blot on the moral landscape of London: an outworn slum area….its crime is not that it contains vice but that it is unashamed and exuberant about it’. This was in 1966, a time when the area was London’s Red Light hotspot with racial tensions to match, but things have seemingly improved – at the junction where the skull was buried there’s an attractive terrace of Georgian houses with some charming doorcases, fanlights and original shopfronts.

This all gives way far too soon to St Georges Town Hall, a Portland stone fronted Italianate building of 1860 with rusticated ground floor and a good run of Doric columns between the large arched first floor windows. To the side is a vast mural celebrating the defeat of Oswald Mosely and his fascists in the Battle of Cable Street in 1936 which neatly leads you into St. George’s Gardens, home of one of Nicholas Hawksmoor’s three East End churches, St. George in the East.

In 1711, Parliament passed an act to build fifty new churches in London to accommodate an ever increasing population and its spread further from the centre of the city. In the end only twelve were built as the commission, which included architectural heavy-weights Christopher Wren, John Vanbrugh and James Gibbs, lost momentum. Finished in 1729 it is a monumental piece of ecclesiastical architecture, less striking than its Spitalfields cousin, Christchurch, but magnificent nonetheless with its vast Baroque Portland Stone tower dominating the nearby skyline. The inside was ruined by bombing during WWII but fortunately the idiosyncratic form of the building survives – a new smaller church has been built within, an unusual and ingenious solution. Today it stands in an anonymous and somewhat forgotten part of the East End, an unusual spectacle amongst not much else but remains a pleasing point of interest for the thousands of cars that pass it daily on their way into The City.

Continuing east along Cable Street one eventually reaches Devenport Street; continue north and adjacent to it to the east on Havering Street is a splendid street of diminutive late Georgian properties. The majority of the lancet windows remain and there some good original cast iron railings with anthemion finials. This street comprises part of the Albert Gardens Conservation Area, formed in 1969; Albert Gardens itself is slightly further east, and slightly unfortunately just off the Commercial Road. The square itself is surround on three sides by elegant late Georgian (c.1830) houses, many with their original doorcases composed of fluted quarter-column and headed by leaded fanlights which bear a distinct resemblance to one LASSCO ourselves hold in stock, click here. The square is mirrored to the north of Commercial Road by Arbour Square, built between 1820 and 1830 and well worth a look.

Finally, heading north we reach Stepney with its more striking examples of urban Georgian architecture. Heading up Stepney Green (the cobbled and more genteel side, of course) one passes the excellent late Victorian red-brick Stepney Court (build by Lord Rothschild for Jewish immigrants) before coming across a number of substantial early Georgian properties with good door-cases, a reminder of when this areas was considered the ‘Millionaire’s Row’ of east London. The finest example by far is Number 37 – built in 1694 this fine five bay house is centred by a set of steps leading to the most wonderful scallop shell door case (to get the Number 37 scallop-hood look from LASSCO, click here). The money from such dwellings came from the spoils of commercial trade from the nearby River Thames – the house was built for Dormer Shepherd, a slave owner and merchant and then Mary Gayer the daughter of the East India Company in Bombay moved in (hence the ‘MG’ in the elaborate ironwork outside). Assiduous restoration was once again undertaken by The Spitalfields Trust in 1998.

Heading north one returns to the Mile End Road. Walk just over 100 metres to the east and one comes across a pair of George II terraced houses to the north. Well shielded from the busy road by bushy foliage, one can just about glimpse through the ironwork gates to see the two five bays properties set back from the road – they both had shop extensions built over their front garden in the nineteenth century, since removed. Plenty has been written about these houses in the press [search for Malplaquet House], but they serve as a reminder of a time when Stepney was infinitely more prosperous than it is now. Another good terrace of four early Georgian properties (built c.1717) is 100 metres to the west. All have attractive matching projecting door canopies with scrolled acanthine brackets – LASSCO holds a similar example in stock here. As before, for those of you with the inclination one of the four is currently for sale and LASSCO are on hand to help correct the many mis-guided interior design choices that some may consider need remedying.

Walking towards The City one passes a vast colonnaded building, an old department conceived as the Selfridges of the East when constructed in c.1910. It houses what can only be described one of London’s great, if humble, architectural triumphs, Spiegelhalter’s. The diminutive property owner refused to sell and caused a fine interruption to the emporium – read an extensive LASSCO news story about one of the city’s most amusing non-conformist flag-bearers here.

Finally the tour ends at the serene tranquility of the Trinity Green Almshouses. Built in 1695 for destitute sailors they are fine example of late seventeenth century architecture and, one could say, social housing. Two rows of houses flank the green which is centred by an attractive chapel with sweeping steps (à la 37 Stepney Green), a Palladian pediment, arched windows flanking the arched door case and a domed clock tower behind. The pair of gable ends which front the Mile End Road are also of note – to the centre of each is an elegant cartouche topped by an aedicule which in turn is flanked by a pair of ships (fibreglass models, the originals are with the Museum of London). Stepney Green at the time of the Almshouses’ construction was essentially countryside, a village outside the great city, only now with the building of the Mile End Road and other modern development are they hemmed in as such. They were under threat of demolition in 1895 until C.R.Ashbee intervened with a campaign that saved them. The monograph he wrote proceeded his Survey of London, which continues to this day.

Further reading:

‘Nairn’s London’ – Ian Nairn

‘East End Chronicles’ – Ed Glinert

Tower Hamlets – The Myrdle Conservation Area

Suggested viewing:

The London Nobody Knows (1969)

Photo credits:

Image 1 – Imperial War Museum, ‘HU 88803’

Image 2 – City of London, London Metropolitan Archives via spitalfieldlife.com

Image 11 – www.wikipedia.org

Image 18 – via pinterest.com